Emily Budd, founder of Aluminati, challenges the norms of monument-making, advocating for diversity and inclusion in public art through her innovative metal sculptures.

As Emily Budd packs her life in Las Vegas into boxes, she is not thinking of what to take or leave behind. She is wondering what projects she can complete before she relocates to Dallas, Texas, for a new academic post. When she first told me she was leaving, she was clear about one thing: she was taking Aluminati with her.

Foundry always felt like a boys’ club. The foundry on the campus of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas existed when I was an undergraduate art student but I never set foot in the sculpture yard until 2022 as a graduate student. That November, during the annual UNLV Art Walk, I wandered into the yard to witness my first pour.

There they were. A yard full of femmes in leather gathered around a flaming oven in the ground. They held ancient iron contraptions, head-to-toe protective gear, casual but confident postures. Something in me lit up along with the crucible.

To those frustrated with the refrain “representation matters,” I say, “seeing matters.” Look, there, sweeping off a helmet and mesh face covering, a bandana holding back a pile of curly hair: it’s Emily Budd, artist, professor, and example of what felt impossible before. To exist as queer is a political act. It is enough.

I recognized something in myself in those women and nonbinary folks. Collectively, they were known as Aluminati, a play on the word aluminum, the recycled metal Budd sources locally for the community monuments they pour. Aluminati is not a fixed group but rather a project founded by Budd. Though not all of them are femme or queer, their inclusion is a conscious effort.

In my conversation with Budd, she has trouble pinpointing the conception of Aluminati. Like the molten primordial matter in a crucible, the concept was developed before it took a specific shape and will continue to be recast to suit the group’s evolving ideas about social practice. However, Budd is clear about the fact that Aluminati came about after several experiences galvanized Budd to challenge the rigid conservatism that has long plagued the field.

Foundry as a practice survives on the creation of monuments, a public art increasingly under scrutiny after the 2020 national reckoning of racism in the United States. Budd cites Monument Lab’s 2021 audit of the top fifty subjects of monuments in the U.S., which found that only five are people of color and none are (known to be) queer. But, before the study, Budd’s personal experience as a queer woman revealed to her the state of monument-making in our country.

There they were. A yard full of femmes in leather gathered around a flaming oven in the ground.

She recalls, “I got to a point where I wasn’t comfortable working in our foundry because the attitudes were just really bad. There was homophobic and sexist language every single day.” In addition to attitudes in the creative spaces, Budd notes, “Even the gear isn’t made for women. It’s really hard to find inclusive sizes.”

The question of monuments—who they reflect, and who decides—is at the core of Aluminati. In 2019, Budd created her own public monument. A slowly eroding structure, Memorial of a Queer Rhyolite, a temporary monument to dreams in the dust cradles a more permanent monument: a “radically small” metal core inscribed, “here lie dreams of Stonewall Park, a safe and peaceful place.” In the 1980s, a gay couple had organized to buy the ghost town of Rhyolite, Nevada, to create an openly queer community to escape discrimination. Though their town of Stonewall Park was never realized, Budd questions whether their dream died at all.

In 2020, New Monuments for a Future Las Vegas, curated by Wendy Kveck for the Nevada Humanities Program Gallery, allowed artists to question monuments as a community. As part of the show’s programming, Budd organized a Queer Foundry Day with Laurence Myers Reese. Budd reminisces, “We locked down the foundry and had a day where [the] foundry… is 100% queer and we are claiming it as queer. […] It’s a Pride Parade on the foundry floor.”

Budd’s interest in social practice developed after years of experiencing public events that purported to empower communities but fell short of that goal. These programs were structured like a service done for communities, rather than a true opening up of the practice to them. Instead of inviting audiences to collaborate, they seemed to further silo foundry practitioners in their specialized world.

Inspired to create radically different experiences, Budd organized students, many of them new to foundry, to create monuments with their peers. In 2023, I became one of those students. Aluminati is collaborative for both the audience and the organizers. We were challenged not only to learn how to pour metal, but to build lasting connections. We were asked to design a monument that proclaimed, “On this day, a community gathered to change the future.” This is a lesson we will carry with us.

It’s no surprise Budd is called a contagious figure in the foundry. A catalytic presence, she has the vision, the energy, and the courage to renew areas long overlooked—literally and metaphorically. She sees an abandoned man cave above the sculpture studio and turns it into a gallery loft with monthly student exhibitions. She revitalizes an ancient practice, illuminating endless avenues of experimentation. She transforms and, in doing so, opens up opportunities for her students.

A foundry is an expensive asset. Metals, such as traditional bronze, are a significant investment. As a result, communities build around the foundry’s hearth, led by mentors vital to the craft. Budd carries this legacy in her teaching practice, fostering an environment where all students feel empowered to innovate while building on centuries of craft.

Finding ways to renew trash is like finding a new identity or something outside a taxonomy—its own identification.

Experimentation was encouraged in the San Francisco Bay Area where Budd pursued her MFA in sculpture at California College of the Arts, Oakland. Mentors Mark Thompson, Clay Jensen, Rebeca Bollinger, and Kim Anno, with their West-Coast “question-everything” attitude, rewarded her risk-taking. This was a breath of fresh air after her first experiences in the foundry.

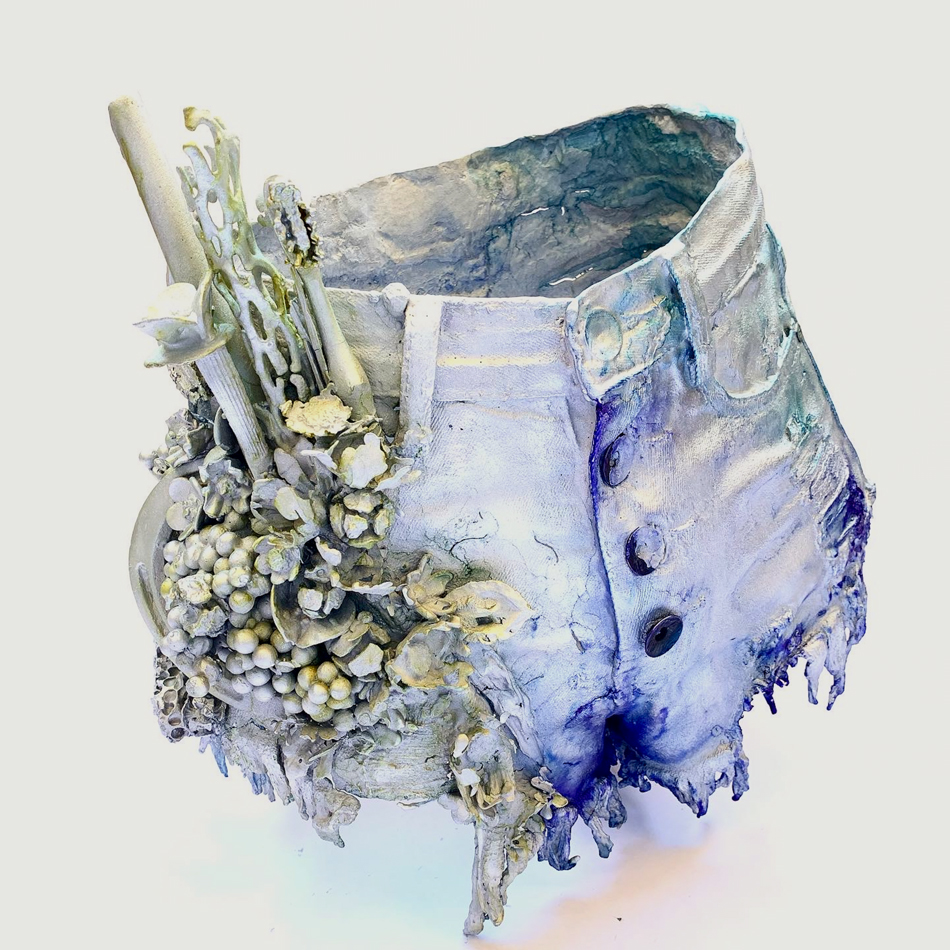

Through experimentation, Budd prompts tough questions and attempts at answers. These processes take years to develop, beginning with materials. When asked about her process, Budd explains, “I approach things scientifically, where I go in with full experimentation by breaking something apart and putting it back together just to see what I can discover.” In this way, Budd gives new identities to familiar objects. “Through this process, I am looking for opportunities for renewal.”

She continues, “I have been thinking a lot about queer renewal and using that as a guiding force. Especially by starting with material that has been broken or abandoned through some kind of cycle. I relate to stuff that has been left behind.” Her background volunteering in a paleontology lab is evident in her fascination with processes that transform organic material into more enduring forms. “Finding ways to renew trash is like finding a new identity or something outside a taxonomy—its own identification.”

As Budd continues to form allegories about sculpture and starts to describe the lost-wax process—where a hollow space shapes a new possibility—I wonder what will fill her absence. Perhaps her experiments have prepared us for our own renewal as this venerable mentor leaves for a more permanent position at Southern Methodist University, as an assistant professor of art in sculpture.

The impact on her students is obvious. When asked to describe how Budd inspired her artistic process, MFA student Bailey Anderson remarks on the empowerment of renewal in her own recycled metal practice: “In the crucible, picture: industrial bars of aluminum cut into small bits, random aluminum thrift store trinkets, failed lost-wax cast investments, and a graveyard of sculptures that have arrived to be reinvented. All of it melting down to become entirely liquified. It pours into a new mold, regenerated in its new form.” Anderson is not the first painter to be lured by the flame of the foundry. With Budd teaching, she won’t be the last.