Early Churches of Mexico: An Architect’s View

by Beverley Spears | published by University of New Mexico Press

Santa Fe preservation architect Beverley Spears’s Early Churches of Mexico: An Architect’s View details her decade-plus study of sixteenth-century churches and conventos in Mexico to thrilling result. Through this work, readers make connections between architecture in New Mexico and the structures of our early Mexican cousins. “When I first saw one of these sixteenth-century conventos, I was totally captivated,” Spears said. “For me it was mainly about the photography at first, but it became a research project. Eventually I started making trips to Mexico once or twice a year to find these churches, learn more about them, and document them with photos.”

“I wanted the photographs to capture how I felt in those places, which was, I suppose, timeless.”

The sixteenth century was a time when Indigenous and Spanish cultures clashed and came together, forming the basis of modern Mexico. The continuing tradition of Catholic worship there means that these conventos are still being used by the local parishes, and Spears notes that “for the community, whose ancestors helped build these places, they have been important community spaces for centuries, and remain so.”

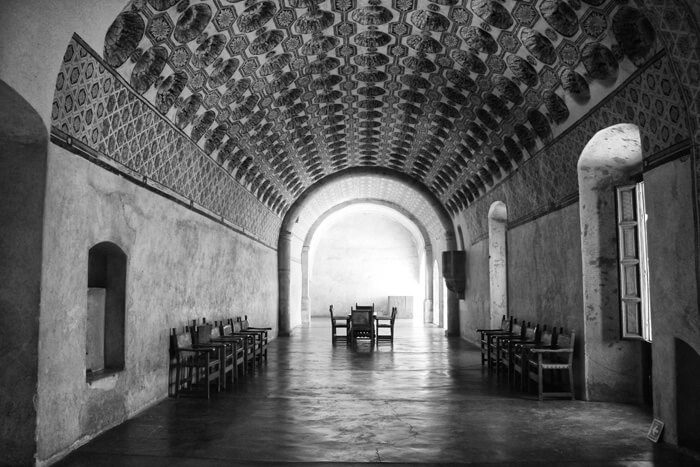

“It is the extraordinary effect these buildings have on us that intrigues me. It is a different way of looking at the built environment than we have in the U.S. It’s not about a building sitting out on a piece of ground,” she describes, “but about the three important volumes—the outdoor atrio, walled and yet open to the sky. […] Then, the cloister—with its gallery and walkways, and wonderful indoor-outdoor richness… plus all the layers of design and symbolism in the art and the murals.” She continues, elucidating the concepts more thoroughly explored in her book: “Then [there is] the church itself… a single nave with a high and tall volume, and the raised sanctuary on the east. That volume—how it feels, how it’s decorated, how the light comes in—all the little elements that are part of it. […] These grand, beautiful spaces affect us whether we are religious or not. […] It’s an architect’s paradise.”

Lest we forget, the later versions of these single-nave churches with attached conventos in New Mexico (like those at Pecos, Acoma, Cochiti, and Isleta) were used as the foundation for the New Mexico Museum of Art (1917), which would become the defining example of the twentieth century’s Spanish Pueblo Revival architectural style.

In addition to insightful histories of these spaces and their communities, a helpful glossary, and plan diagrams of the churches featured, Spears’s black-and-white photography—some three hundred photos—is stunning. An exhibition of seventy of the pieces is currently traveling around Mexico, having already visited San Miguel and Durango, sponsored by Fomento Cultural Banamex.

The photos are, after all, the heart of the book. Spears surmised, “Most of the photos are unedited, except to perhaps remove a distracting phone wire, so that what remains is an accurate rendition of how the building is in the early twenty-first century. I wanted the photographs to capture how I felt in those places, which was, I suppose, timeless.”