Mill Contemporary, Santa Fe

October 7-November 20, 2016

What a felicitous curatorial idea, the juxtaposition of this trio of artists. Pokrasso, Stanford, and Glovaski continue to explore new media, methods, and avenues of expression within the arc of their concerns. The works share an intense focus that is clearly long term. These are artists who have been working for many years; every element feels necessary and deliberate, even in works that are explorations or experiments.

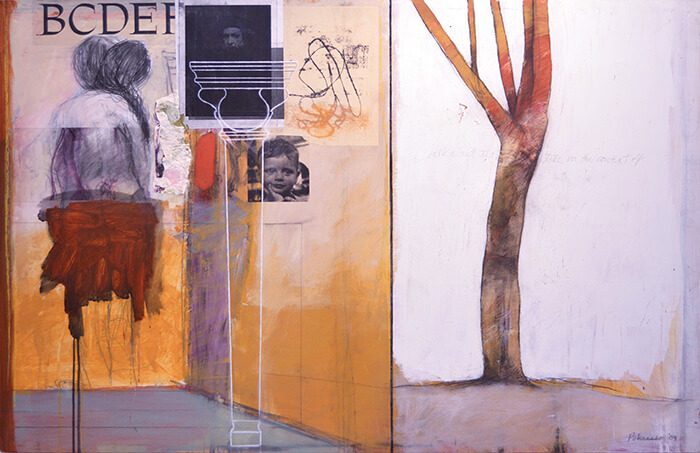

Ron Pokrasso’s works on wood or paper have many concrete real-world representations or references (trees, human and animal figures, sheet music). But they inhabit or, more precisely, generate their own world, usually tripartite. Most are roughly divided into three image/concept/medium zones, giving them an implicitly narrative feel. This is reinforced by a couple of works that resemble the spine and covers of a book splayed open, face down. Pokrasso combines drawing with other media, in this case printmaking techniques. Some works actually extend into the realm of construction, with collaged items such as keyboards extending out of the picture plane. Combined with drawing and collage, this makes for dense visual surfaces. The viewing dynamic for me was one of agitation stimulated by such variety and nudged toward seeking narrative structure by implied multiple panels or windows, by the associative power of graphic imagery, even by the titles of the works. My favorite pieces were Late Summer Stroll and Tree View Palette Fig*, using acrylic, collage, drawing and intaglio. Both have the three-part structure which has built-in contradictions; it suggests a yearning for something that unites the three, while a pose of self-sufficiency by the segments tends toward an impulse to hide those connections. Pokrasso often uses monotype, which, strictly speaking, is a transfer technique rather than a maker of multiples, like etching and intaglio. This is part of what makes each piece idiosyncratically unique.

The universal struggle for balance between control and accident, between stasis and chaos, animates the surfaces of Glovaski’s paintings, just as it does our lives.

Doug Glovaski’s arrangements of what appear to be bright colored rectangles of construction paper embed an ambiguity at the heart of their geometric rigor. With the exception of a beautiful painting called Holy Ghost, these acrylic-on-canvas works bear titles from one of two numbered series: Mechanism and Influenced by Invisible Forces. This points unambiguously to the concerns that underlie these works. The rectangles of color are connected by pulley-like images of circles, arcs, and lines indicating perhaps the intention to rearrange them but more broadly the vast realm of possibility in the relations among geometric forms. This charges the hyper-controlled rendering with the underlying threat/hint of change and instability. The universal struggle for balance between control and accident, between stasis and chaos, animates the surfaces of Glovaski’s paintings, just as it does our lives.

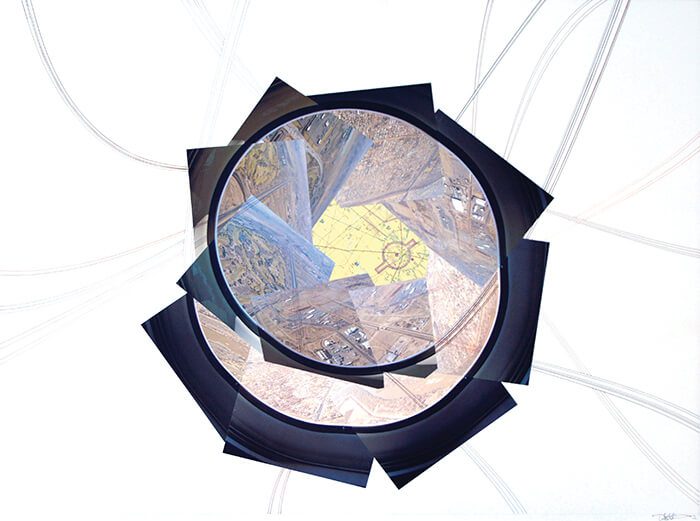

Verne Stanford’s photo collages are complex commentaries on vision and perspective itself; each one enacts an instance of the way that how we see is constructed (and never more flamboyantly than when an artist is in charge). Stanford’s background in architecture is evident in works such as Blue Suspension and Taunt (Blau Tents), where a sense of contained space and of supporting structures is skillfully conjured through color and overlapping, fanned-out photographs. Many of the photos, all taken by the artist, are aerial shots. The bird’s-eye view is crucial to these works. Another prominent element in these works is the line: seen from above, land, buildings, roads, and natural features of landscape form a composition. Stanford tweaks this Cartesian tendency in the viewer by cutting up and rearranging views and adding multiple perspective lines that extend either some linear feature of the original photograph or the edge of another into the plentiful white space surrounding the images. It’s a sophisticated ploy that, while bridging drawing and photography, also reveals perspective to be a conceptual imposition. Extended Iris, referencing both the human eye and a camera aperture, clinches for me that this work is about how, with both our devices and our inherent perceptual apparatus, we formally (and quite contingently) organize the world.