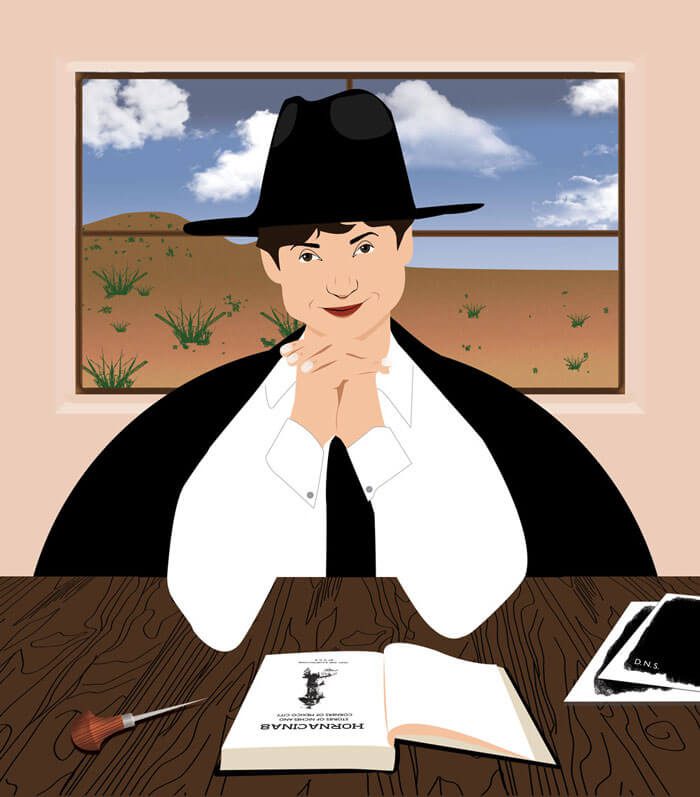

Name: Dorothy Stewart

Signature: D.N.S.

Born: April 8, 1891, Philadelphia

died: December 24, 1955, Mexico City

known for: Printmaking and running El Zaguán artists’ colony with her sister, Margretta Dietrich

Dear Toad of My Heart, begins one of the two thousand pages of letters between Dorothy Stewart and Maria Chabot in the Georgia O’Keeffe Research Center. “Dearest Thing,” begins another. These letters are a remarkable record of two women in love in the 1920s and ’30s and their various heartbreaks, jealousies, friendships, and new loves along the way. Stewart moved on from Chabot (who was being possessed equally by two employers, Mary Cabot Wheelwright and Georgia O’Keeffe) to Agnes Sims, a sculptor and later the partner of Mary Louise Aswell, editor of Harper’s Bazaar. Of course, if you read about any of these women, you will learn merely that they were “dear friends” and “traveling companions.” (For the uninitiated: these are code words for huge lez.)

Meanwhile, if you Google “Dorothy Stewart Santa Fe,” the results are almost all from hiking and travel websites informing you about the location and difficulty level of the Dorothy Stewart Trail, which is how I first learned her name myself. The trail occupies what used to be Stewart’s property near Atalaya Hill, where she kept a studio, and the portion that hikers and bikers and dog-walkers frequent today was donated by Irene Von Horvath to the Forest Trust after Stewart died. But dive a little deeper into Santa Fe’s history, and you’ll find Stewart at the center of a number of knots entangling Canyon Road and Mexico City, artists, writers, and tastemakers of early Santa Fe, and somewhat melodramatic lesbian sagas: a true queer history that has yet to be written and that endures today.

Stewart was one of the wealthy, educated white women artists who settled in Santa Fe in the 1920s and ’30s. Stewart’s early life supported and encouraged her artwork: she attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, traveled to Italy and Greece, and attended the American School of Fine Arts in Fontainebleau. She and Margretta Dietrich passed through Mesa Verde National Park en route to Santa Fe, where Dietrich was speaking at a meeting of the League of Women Voters. A year later, after eating at the Blue Parrot on the corner of Palace Avenue and Burro Alley, the sisters bought a nineteenth-century adobe hacienda on Canyon (at that time, Cañon) Road and began to host and attend galas and parties. Dietrich bought a second home on Canyon adjacent to her first, and Stewart created a studio nearby that would eventually be known as El Zaguán, the artists’ residency still active today. At the studio, which was called the Galeria Mexico, Stewart held a variety of performances and lectures, where as many as fifty people attended (a massive audience for Santa Fe, as we all know!).

Next she had a Baby Austin that looked like a sheepherders wagon, with hoops and sheeting instead of a roof.

Stewart, a printmaker and illustrator, published her first book in 1933. Hornacinas, Niches and Corners of Mexico City maps Mexico City before it had an address numbering system, using works of art, usually sculptural figures of saints, located in niches and alcoves on buildings. Stewart made linoleum block illustrations for Spud Johnson’s Laughing Horse Press pamphlet on traditional Southwest building techniques, Adobe Notes, and created a mural for the entrance of the Little Theater in Albuquerque for the WPA. In 1948, she bought a printing press from a Spanish-language newspaper in Española and moved it in pieces to Canyon Road. Eventually, after assembling the press, she began printing and launched Pictograph Press, creating illustrated Shakespeare plays, a Handbook of Indian Dances, and San Cristobal Petroglyphs, a collaboration with her partner Agnes Sims.

Stewart loved cars, and her first was a “new Ford Model T frame with a Packard body salvaged from a junkyard.” Next she had a Baby Austin that looked like a sheepherders wagon, with hoops and sheeting instead of a roof. Stewart drove all over New Mexico, despite the unpaved roads, to find petroglyphs that she drew and eventually made into linoleum block illustrations for her books. The press came to an abrupt halt with her early death in Mexico City in 1955, where she succumbed to a brain hemorrhage with an old friend, Maria Chabot, at her side.