Documenta 15, the globally significant quinquennial, was both an exercise in decentralized curation with a focus on the Global South and a show riddled with unrelenting controversies.

KASSEL, GERMANY—If you’ve read anything about Documenta 15, you probably know that the Indonesian art collective ruangrupa was invited to curate 2022’s iteration of the famed quinquennial. You’ve probably heard terms like “lumbung” and “ruruHaus.” You’ve probably also caught wind of the allegations of antisemitism that have run roughshod over the mainstream media coverage of the exhibition and relentless controversies that have rocked the German cultural sector, leading a director of Documenta to resign and a member of ruangrupa to appear before Germany’s parliament.

Documenta 15 has been met with mixed reviews and wild speculation, some suggesting that the end might be nigh for Documenta’s global influence, if not the demise of the institution itself. I find this speculation to be reckless and defeatist. The installations I saw in Kassel were exciting, flawed, risky, chaotic, compelling, eye-opening glimpses of a shift toward a decentralized model of curation, and represented what a global “art scene” looks like—one that resists containment and characterization as a single system. If art-world mega-events like the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale show us the 2 percent “top” of the art world, Documenta 15 may have found its strength in sharing the other 98 percent with the world, warts and all.

The Documenta organizers have written of the challenges and risks involved in their approach and openly address that the decentralized curation and social art-making embraced by their edition of Documenta are at odds with the art-market infrastructures of transaction and commoditization that circle other biennials.

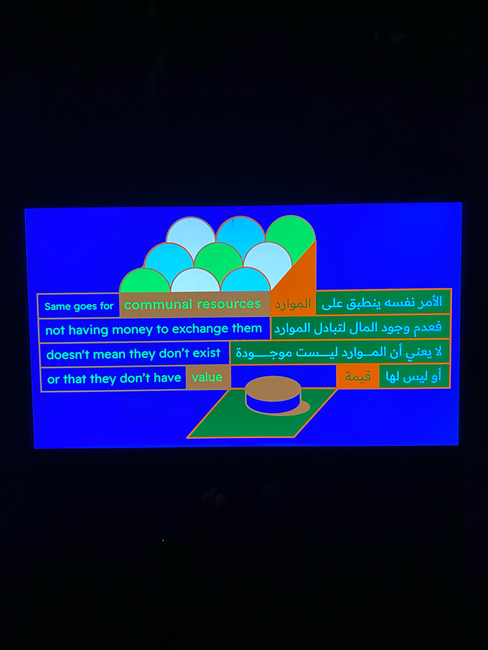

To the artists involved, Documenta 15 is also known as Lumbung 1. The term “lumbung” refers to a tradition in rural Indonesia of communal rice barns: members of a community contribute the surplus of their rice harvest to a communal barn from which members can draw rice as needed.

Ruangrupa adopted this model of mutual support as a guiding principle. They invited fourteen other collectives to co-curate with them. Those fifteen collectives invited fifty more collectives to participate. In total, more than 1,500 (primarily non-European) artists participated across more than thirty venues. All of these artists and collectives make up the lumbung and are referred to as lumbung members throughout the show’s materials.

In the catalogue, ruangrupa points out they, in turn, invited Documenta to be a part of the project—a gesture resulting in a sense that the lumbung effectively occupied Documenta 15, an inversion of the typical understanding of a host institution inviting artists and therefore bestowing its stature and credibility upon them.

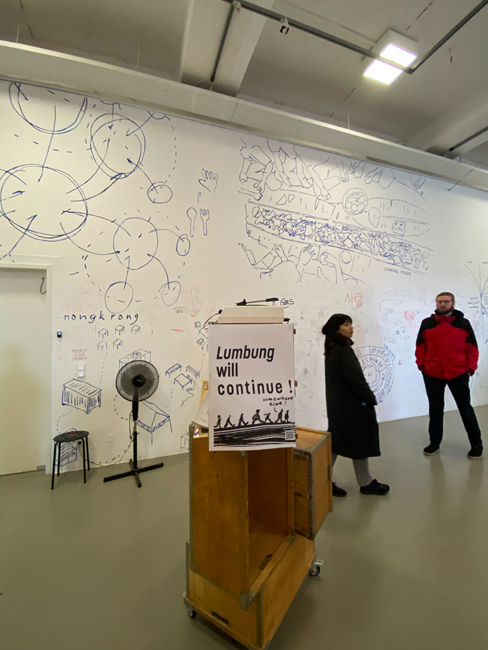

Much of the planning of the exhibition took place during the 2020 pandemic, and lumbung members primarily met in smaller assemblies (“majelises”) via Zoom. Closer to the time of installation, some lumbung members took up residence in exhibition spaces of the Fridericianum (“Fridskul”). Visual reminders of the labor of artistic and creative work, the sketches, notes, and remnant pieces of these living spaces were left visible in several of the core installations.

Lumbung members also established several working areas that were continuously activated throughout the 100 days of the show. One was the Lumbing Press, a printing workshop in the middle of the Documenta Halle surrounded by stacks of paper and ink, where lumbung artists could print their own posters and publications. Artist Graziela Kunsch created Public Daycare, a daycare facility that was free for babies up to three years old. Living-room-type spaces with mismatched couches and coffee tables punctuated many of the venues, which looked like lumbung meeting points but served as welcome rest areas for viewers with weary feet (I personally encourage the biennials of the world to embrace greater care for their visitors).

Another lumbung term found throughout the show was that of translation, which they define as a “poetic way of bringing a project already existing in touch with more potential users. An alternative logic to commissioning, lumbung members and artists were asked to keep doing what they are doing while translating their practice to Kassel and back.”

Take the Wajukuu Art Project, a collective rooted in Lunga Lunga, one of Nairobi, Kenya’s most densely packed slums. Per the catalogue, we read that the collective’s work in Lunga Lunga involves the material conditions of their community: the “improvised functionalities” of slum architecture and the preservation and reinvention of cultural heritage in an economically challenging environment. We see images of artists painting sheet metal walls and planting trees during a “slum art” and music festival.

In Kassel, we see an admittedly hokey architectural installation that evokes slum architecture, dark spaces encrusted with rusty corrugated metal, multimedia art objects, and a documentary film about the project, all with limited wall text. Wajukuu Art Project’s installation requires patient investment in seeing the aesthetic presentation as more or less an imperfect lens on the work the collective is doing in and for their own community—work that is materially inseparable from life. Under this circumstance of partiality, it is impossible to see the complete picture—but I consider this a feature as well as a flaw.

Many projects placed similar time demands on Kassel-based viewers. Several projects showed the work of collectives invested in archiving practices, such as The Black Archives, a collective based in Amsterdam that has collected more than 10,000 books, documents, photographs, films, and artifacts documenting the history of people of African descent in The Netherlands. In addition to making these resources available for study and research, the collective also stages exhibitions and programs for the public to learn about an otherwise neglected history of colonialism and slavery.

Another project, Archives des Luttes des Femmes en Algérie (Archives of Women’s Struggles in Algeria), founded in 2019, is building an archive of materials related to Algeria’s history of women’s movements and women activists since the country’s independence in 1962—stories unknown to a wide audience.

One of the criticisms of Documenta 15 has been in regard to a lack of, or seemingly disappointing, aesthetic experience on the behalf of viewers. New York Times critic Jason Farago wrote that he left Documenta “depressed and disheartened, less by the art itself (which was pretty uniformly forgettable) than by the indifference it showed to its public, and the strange satisfaction it took in being unappreciated.” What Farago deems “indifference” I take as the lost-in-translation difference between documenting and showing meaningful work, versus actually doing that meaningful work. Besides, what is “owed” to the viewer, if anything? Must the aesthetic experience be the goal? During the three days I spent with Documenta, I was struck by how much my own experience didn’t really matter; by how often art stops at being an aesthetic gesture; by how the work displayed by lumbung artists instead endeavored to master the show-don’t-tell approach.

In St. Kunigundis church in Kassel’s Bettenhausen district, Haiti–based collective Atis Rezistans (Resistance Artists) staged a micro-iteration of their Ghetto Biennale, a biennial the collective has been presenting in Port-au-Prince since 2009. Here, found-object assemblage sculptures evoke Haitian history, vodou, and pop culture. According to accompanying text, the Ghetto Biennale is organized around the probing question, “What happens when first-world art rubs up against third-world art? Does it bleed?”

Farago’s dismissive, contemptuous take on the lumbung’s “indifference” to the viewer suggests “yes,” and may be a reaction to a new, newly uncomfortable approach to what art is when it grows out of real needs, expressions, and heritages of global communities. The question of whether some viewers in some other country think it’s interesting, beautiful, or good is not the primary concern.

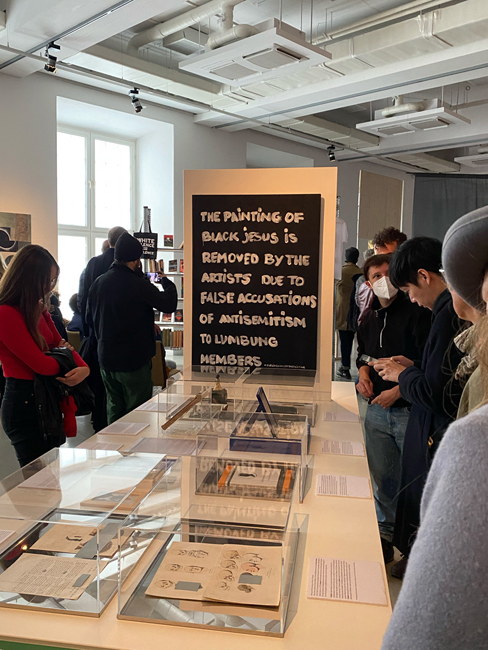

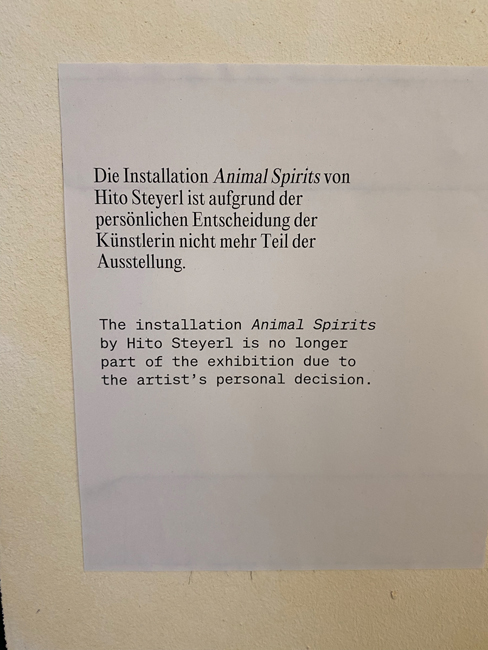

To complicate an already complicated narrative, Documenta 15 and the lumbung have been plagued by knee-jerk, blanket accusations of antisemitism, which have been exceedingly well discussed and publicized. Contention first grew over the inclusion of Palestinian collective The Question of Funding. Panel discussions to address the allegations were planned, and then canceled; accusations escalated to instances of vandalism and threats. (The narrative is well laid out by Jörg Heiser for Art Agenda.) Then, when the exhibition opened, the mural Peopleʼs Justice (2002) by post-Suharto Indonesian collective Taring Padi contained an overtly antisemitic caricature. The mural was first shrouded in black fabric, then removed. Public apologies were issued. Hito Steyerl, one of the few internationally recognizable names in the show, withdrew her work. The director of Documenta, Sabine Schormann, resigned. Ruangrupa and lumbung members have issued verbose open letters in response throughout. A member of ruangrupa even spoke at a hearing before Germany’s national parliament.

Not being an expert in all of the relevant German, Indonesian, and Middle Eastern histories—as, scholar and critic Michael Rothberg points out, many of us are not—I don’t have the visual literacy to make sense of these multifaceted questions. But this episode should be a catalyst for more productive, less anxiety-ridden discussion, and care should have been taken by Documenta to contextualize and facilitate such dialogue. Examinations of the antisemitic imagery at hand have been vanishingly few (at least, in English-language media), as though critically engaging with difficult, hateful imagery might result in some kind of contamination. For instance, few have interrogated the circuitous paths of colonial influence that result in the presence of European antisemitic imagery in Southeast Asian political artwork, not to mention the historical overlap between colonialism and the Holocaust or contemporary Germany’s anti-antisemitic anxieties.

Rothberg provides a thoughtful formal analysis of the imagery in People’s Justice and an unpacking of these complicated histories in an article for the New Fascism Syllabus, and concludes that the case of People’s Justice suggests “we need to unlearn our certainty, our moral superiority, and our presumed innocence in order to learn anew about the entangled histories that implicate us in the larger dynamics of race, antisemitism, colonialism, and genocide—histories that have made us all who we are. Perhaps those processes of learning and unlearning could represent a small, but necessary step toward a true people’s justice.”

I left Documenta 15 feeling the fragmented, frictious global world of art and visual culture—in which innumerable communities are creating art and culture without much recognition or fanfare—is tantalizingly, electrifyingly vast. Studying the Taring Padi incident, however, tells me that we are all more connected than we may feel, that our shared histories are boomeranging around the globe—for better and for worse. Coming into contact with these far-flung projects and encountering them side-by-side is a rare opportunity to confront the complexity of the current moment and embrace our humility—if we can find the patience to look and listen.