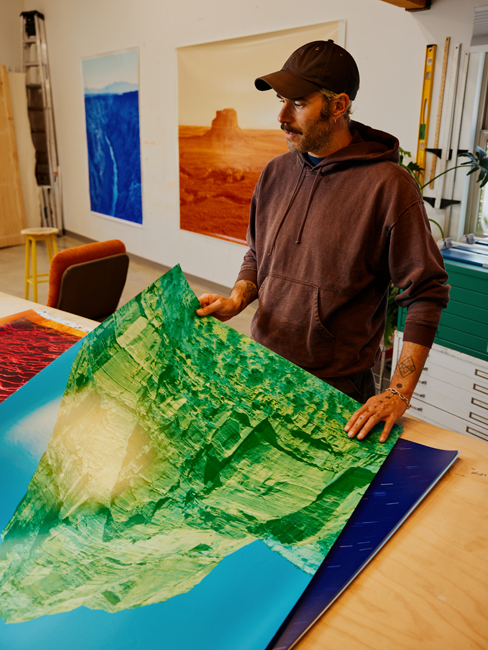

Santa Fe-based artist David Benjamin Sherry discusses the emotional and physical landscapes within his work, and the parallels between disappearing landscapes and losses of life.

1.

I walk up metal stairs to David Benjamin Sherry’s second-story studio on Lena Street in Santa Fe. The artist is waiting on the balcony and walks me into his studio.

The space has high ceilings and generous light. A red-orange chair with a dark wooden frame sits next to a pale beige leather couch with a metal frame. Both face the front windows.

Sherry has arranged several of his large landscape photographs along the white walls. As our conversation progresses, we move from one to another.

The first is a vivid blue image of the Rio Grande Gorge.

My eyes trace the curve of water, the cement-like consistency of the rock, the gentle, wavering line of mountains above.

“The longer you look, the longer you reflect on the land in this place and the motive force of color. There’s a kind of poetic distillation that happens from the experience of seeing a photograph.”

I notice light falling diagonally across the surface of the print. David sees my eyes move in that direction.

“When I’m taking photographs, I think a lot about light, space, and time. Sometimes I stand for a long time waiting for clouds to pass, light to change, or wind to stop. I’m constantly waiting for wind. Most people don’t know this about large format photography—the wind can move the camera, the film… you have to take it into account.”

2.

I glance over at a photograph of a burnt orange butte in Chaco Canyon. The sky remains mostly white, removed from the landscape. The deepest color is along the ravines.

Sherry explains that he began to photograph Western landscapes after the death of his best friend, Lily. He makes a gesture with his hands and I see a tattoo of her name on one of his wrists.

“Lily helped me come out and understand my identity. She recognized my art practice as a tool of self-discovery and encouraged me to pursue graduate school. I loved her deeply, so losing Lily led me into the wilderness. I say wilderness, but I mean national parks, national monuments, what felt like true wilderness to me then.”

For several weeks, Sherry camped and hiked alone with his large format camera. He pauses.

“I still don’t tell people I’m queer when I’m alone backpacking. For instance, I’ve met many strangers over the years, more recently with MAGA hats, and they chat me up about the mountains or a bear. The question always comes up, ‘Where’s your wife? Your kids?’ And I kind of go back into the closet. I retreat, because I don’t want to get into it… I just want to work. I want to have my experience, but it makes me aware of my otherness—which is part of this performance of identity.”

3.

In July 2023, I attended Blue Monsoon, an exhibition of Sherry’s photography and paintings at Smoke the Moon in Santa Fe. I say I admire how he seems to shift seamlessly between the two media.

“During my adolescence, I struggled intensely with my identity and shielded myself by constantly learning to fit into other molds—which is a form of code-switching. I’m grateful I had a very supportive and loving family, but I didn’t find a queer community until I came out in my mid-twenties. I think, inherently, I brought those coping skills [from childhood] into my adult life and work.”

On the back wall of Sherry’s studio, shelves are filled with jars of matte acrylic paint in colors like cobalt teal, blue violet, and permanent green.

“There’s a lot I’d like to explore with the paintings and photographs. I hope they become more intertwined further down the road, but sometimes it’s really emotionally and spiritually difficult to make photographs.”

David looks at the photos on the wall, then back at me.

“Making paintings is an equally hard technical and creative challenge, but the physicality and emotional heaviness I feel as a deep-earth person makes photography especially difficult. Over the last twelve years or so, I’ve watched and recorded our landscape drastically change. With photography, I feel like I have this third eye that sees and feels something beyond the visual component, but I can’t turn it off.”

4.

I notice a photograph of a bright green rock across the room. The color draws my attention.

I see long striations of rock, a narrow arch revealing sky above and below, dark shadows to the bottom left, nearly out of frame.

“People tell me the photographs have this very positive, kind of energetically charged optimism. I love that, but I wonder if maybe, for the work to exude this optimism, I potentially have to become more of a pessimist… that the work drains it out of me?”

Sherry explains he is not a pessimist, but photographing the same locations year after year sometimes feels like documenting the loss of a landscape rather than its presence. I tell him that, in my experience, people willing to sit with loss (and the fear of further loss) often offer the most solace to everyone around them.

“There is a connection between photography—analog film photography, light being recorded on film—and death. Recording something impermanent, now past, making a physical memory. I’m still drawing parallels between loss in photography and life. Maybe, through loss, we gain a new way to see? I think a lot about how, when I’m gone, this work is what remains of my communion with nature, my practice, my life as an artist.”

5.

As I leave, I take another look at my favorite photograph.

Below columns of yellow sunlight breaking through a cloudy sky, sand dunes gently curve in on themselves. The dunes resemble the back of a person sleeping on their stomach. There is no visible wind. Only thin creases in the sand left by wind.