SITE Santa Fe curator Brandee Caoba’s generous yet discerning way of being in the world, the studio, and the exhibition space supports artists and audiences alike.

Saying yes, as both an artist and a curator, is SITE Santa Fe curator Brandee Caoba’s generous yet discerning way of being in the world, the studio, and the exhibition space.

“I’ve always gravitated toward creative work that challenges me, gives me space to grow, and provides opportunities for others,” says Brandee Caoba, curator at SITE Santa Fe. “And I think curatorial work is a natural fit for that. It’s definitely been a practice of saying yes, in many ways.”

The curator has kept her own creative practice going over the years, often working collaboratively because, as she explains, she finds it liberating to make work without authorship. Since 2014, she has been working with The Human Beast Box, a loose knit group of creative people making punk rock puppetry films. Between 2016 and 2019, they created three films, including The Love That Would Not Die, a film about a lone survivor of a zombie apocalypse. As many things have been since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the film turned out to be a bit prophetic.

Although Caoba has done just about every job there is to do in the art world—running an alternative gallery space, working as an arts administrator, and being an art handler—she didn’t set out with the ultimate career goal of becoming a curator. But it’s her spirit of curiosity that branches out to connect both her artistic and curatorial practices.

In her role as curator at SITE Santa Fe, where she’s worked since 2015, Caoba’s artist-centric approach often means supporting artists rather than providing strict answers. She veers from defining and explaining everything, instead embracing the questions that stem from conversation and critical thinking, making space for the real magic that can happen when people bring their individual experiences and questions to the artworks, and figure it out for themselves. And with that form of support comes a significant amount of responsibility.

“I definitely recognize my position as a place of privilege, and I strive to use it to elevate the voices and visions of other people,” she says.

Caoba’s creative, professional approach has brought her into contact with artists who are bringing about positive change in the world.

“I strive to work with artists and creative projects that offer unique ways to see and understand the world, or at least spark challenging conversations, or maybe lead to advocacy or action in some way,” she says. “But I also see beauty and creativity as acts of radical resistance.”

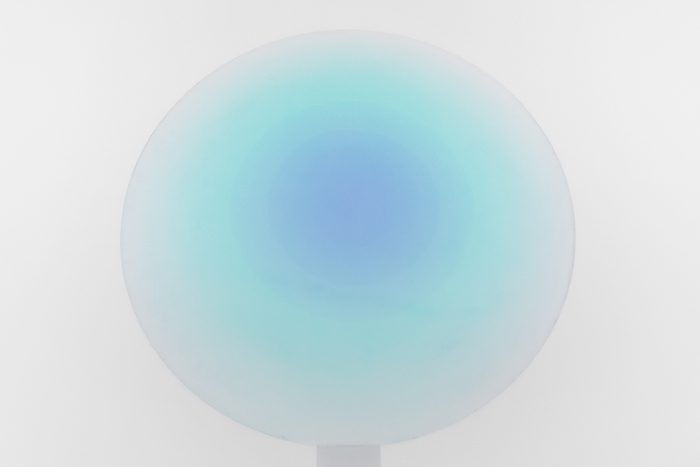

For example, Caoba recently curated Helen Pashgian: Presences, an exhibition celebrating Pashgian’s contributions to the Light and Space movement of the 1960s in Southern California. At almost ninety years old, Pashgian’s works have gone largely and historically underrecognized. With Caoba’s own experiences as an artist—especially her understanding of materials and process—she is able to talk with museum visitors about Pashgian’s inventive methods of working with color, light, and perception in the solid form of resin.

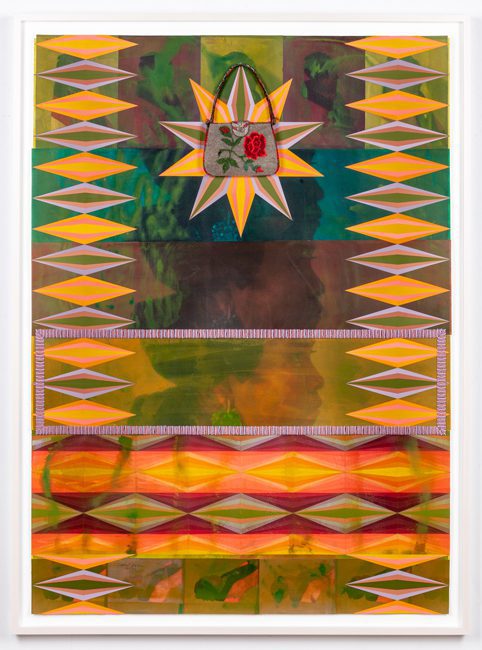

Currently on view through August 21, 2022 is SPECTRUM, a solo exhibition of works by Nani Chacon (Diné, Chicana) that includes newly commissioned large-scale paintings, a double-sided woven tapestry, and a survey of the artist’s public murals and personal archive. The show is described as one that “explores cultural repair and radical colonial resistance through masterful visual storytelling and re-telling,” with the pieces drawing connections between story, space, and time. Developing SPECTRUM was a chance for both Caoba and Chacon to draw attention to important issues such as representation of Brown women in art and the continuation of Indigenous cultures.

“I always consider art to be a vehicle for rousing critical awareness and consciousness of the world around us,” says Caoba.

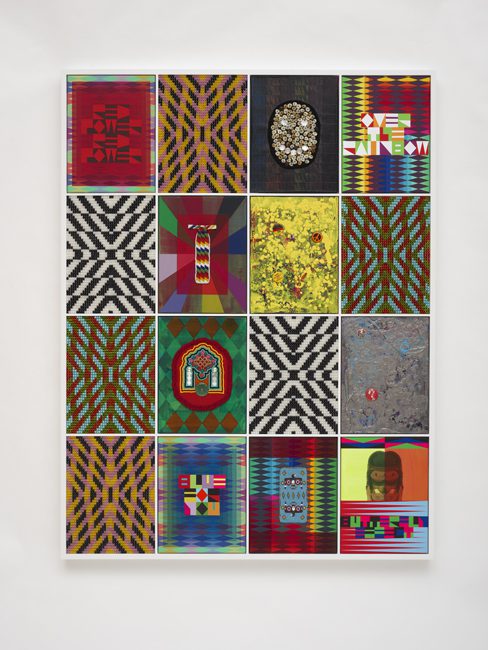

The Body Electric, a survey of multidisciplinary artist Jeffrey Gibson’s paintings and sculptures, as well as a video installation, community-engaged performances, and a large-scale mural, is also currently on display at SITE Santa Fe (through September 11, 2022). The show highlights expression as related to representation, exclusion, and belonging in Gibson’s signature colorful, patterned handling of material.

By commissioning works such as these, SITE brings artists and audiences together for meaningful experiences that extend far beyond the museum walls.

“A lot of what keeps me energized and engaged is the idea that we, at SITE, are investing in new ideas, and we are helping artists manifest new work as opposed to collecting. It’s a joy for me to do this work,” says Caoba. (SITE Santa Fe is a non-collecting institution.)

Some of those new ideas can be seen in the upcoming exhibition Shirin Neshat: Land of Dreams, a project that the Iranian-born, New York-based artist and filmmaker conceived of while spending time in Corrales, New Mexico. The show will include approximately 100 photographs, a two-channel video installation, and a feature-length film, all of which explore how dreams—while deeply personal—are a point of universal connection.

Caoba also says that exhibition-making requires much more than simply a curatorial vision. It’s a constant state of negotiation from the moment of inception to opening night, then to its reception by the public and the media. From there, the show takes on its own journey and will forever be shaped by time. And time, as we know, shapes us all.

“There’s been just so much trauma with the pandemic and climate change and global displacements. And we’ve bore witness to the rise of white supremacy and its return to mainstream politics,” says Caoba. “We have to continue to confront how deeply embedded the legacies of racist structures are in our schools, media, government, and institutions. For me, moving forward, I’m constantly asking, ‘What is the role of the museum? How do we serve our community?'”