At the Amon Carter in Fort Worth—known as “Cowtown”—the exhibition Cowboy made waves by reimagining the mythology surrounding the American cowboy.

Cowboy

September 28, 2024–March 23, 2025

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

There is not a more quintessentially American archetype than that of the cowboy. The lore is both popular and beloved: the fated rivalry between “cowboys and Indians,” the wide-open plains, the rugged individualism.

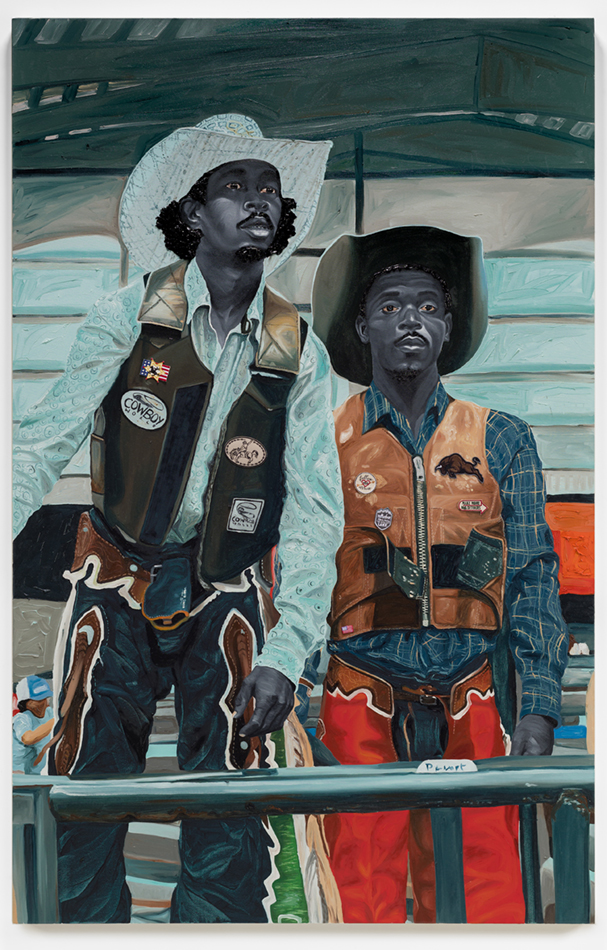

In the city of Fort Worth, Texas, known as “Cowtown,” an exhibition titled Cowboy made waves by reimagining and reexamining the traditional mythology surrounding the American cowboy. The group exhibition was organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver before traveling to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, whose permanent collection was built on depictions of the Old West by artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell.

Of the twenty-eight artists featured, I was intrigued to see how artists living in the Southwest unraveled the clichéd “cowboy” narrative.

One altar-like display features objects and clothing that artist Gregg Deal (Pyramid Lake Paiute) uses while performing, reimagining the stereotypical roles Indigenous people often play in historical accounts as he takes on the imagined persona of a futuristic figure named Toge Pudu (Not So Long Ago). Los Angeles–based artist rafa esparza, in collaboration with Dallas-based artist Fabian Guerrero, created a large installation featuring paintings, photographs, video, sound, and an adobe floor with dancers’ footprints highlighting queer Norteño (a subgenre of regional Mexican music) culture. Arizona-based artist Angela Ellsworth fashions prickly bonnet sculptures out of corsage pins, referencing oppressive gender roles reinforced by societal and religious norms.

Less than two weeks after the exhibition opened at the Carter, it mysteriously closed for a few days with no explanation. When it reopened, a new sign stood at the entrance of the gallery warning visitors of “mature content”: the museum’s remedy to visitor pushback. This reaction especially indicates why we need more exhibitions like Cowboy in cowboy country.

I find myself wondering what the residents of Cowtown struggled with more: the diverse, contemporary depictions of cowboys that counteract the homogeneous, hypermasculine tales? That the Remington and Russell illustrations, alongside Hollywood representations, were exploited as a tool for diplomacy and the justification for land appropriation? Or, perhaps, that the romantic myth of the heroic, John Wayne-esque cowboy protagonist is only that—a myth?