Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, Santa Fe

October 4 – 30, 2017

One of humanity’s most important accomplishments, after the invention of written language, is the application of systematic measurements to things like distances, weights, codified sizes of this or that object. Applying number to the concept of a standard measurement has at its root level of significance a kind of spiritual dimension. The truth of numbers can be seen as part of the meaning of the universe—the reality of pi, for example, or in the case of the artist Constance DeJong, the existence of phi.

Mathematicians and scientists, along with philosophers and certain artists, have been enthralled with the idea of a deeply embedded logic in the nature of existence. Some numbers simply will not lie in their constancy as in the reality of pi and phi—the latter referring to the Golden Ratio, also known as the Golden Mean and the Golden Section. And consider one more: the Feigenbaum Constant, which, in the study of dynamical systems, or Chaos Theory, revealed that a system will move from an orderly into a disorderly state by an unexpected but constant number—a geometric convergence as it’s called—a predictable, incremental transition on the way to chaos. And the Feigenbaum Constant, along with pi and phi, is part of the hidden but provable nature of universal law. And for some artists the seemingly dry quanta of mathematical truths are full of rare and juicy metaphors, just waiting to be employed and expanded into the realm of the visionary.

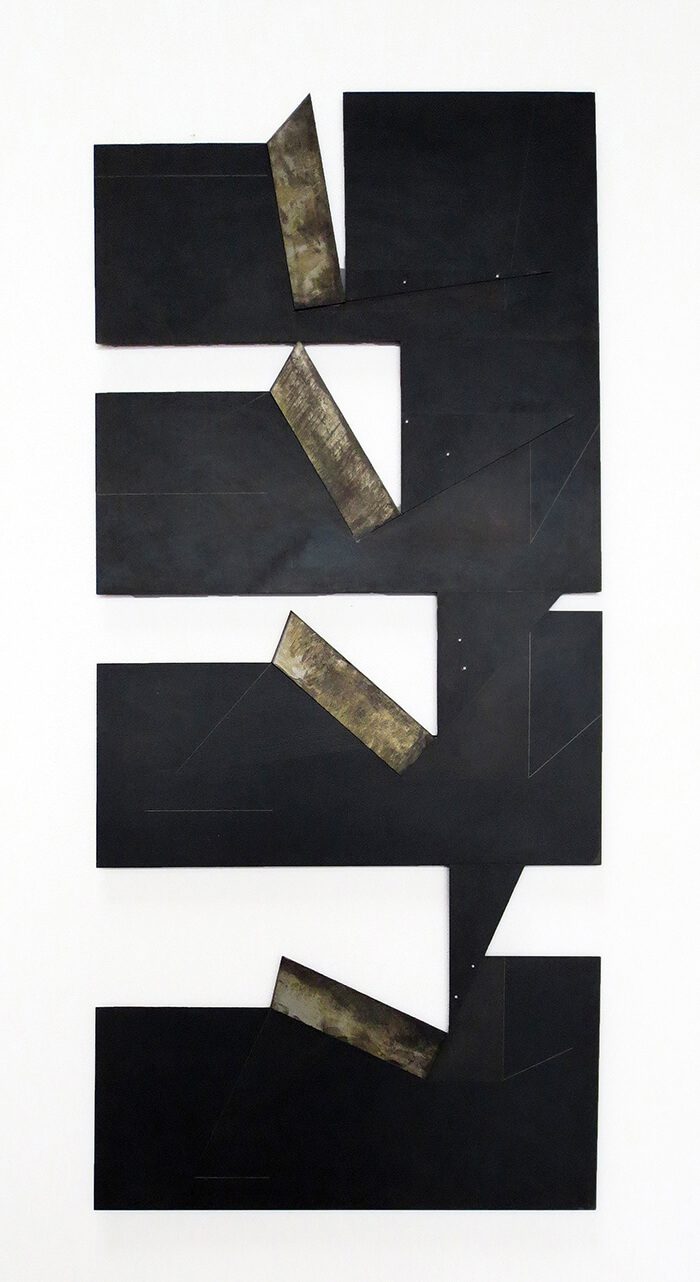

The work in DeJong’s exhibition represents over thirty years of her use of certain materials, precise geometric calculations, and the ephemera of shadows and reflections—the precise and the angular combined with the luminous and the deliquescent. And DeJong’s ephemera are just as important, if not more so, than the rigorous methods with which she strategizes over her sheets of copper, paper, and her lengths of wood.

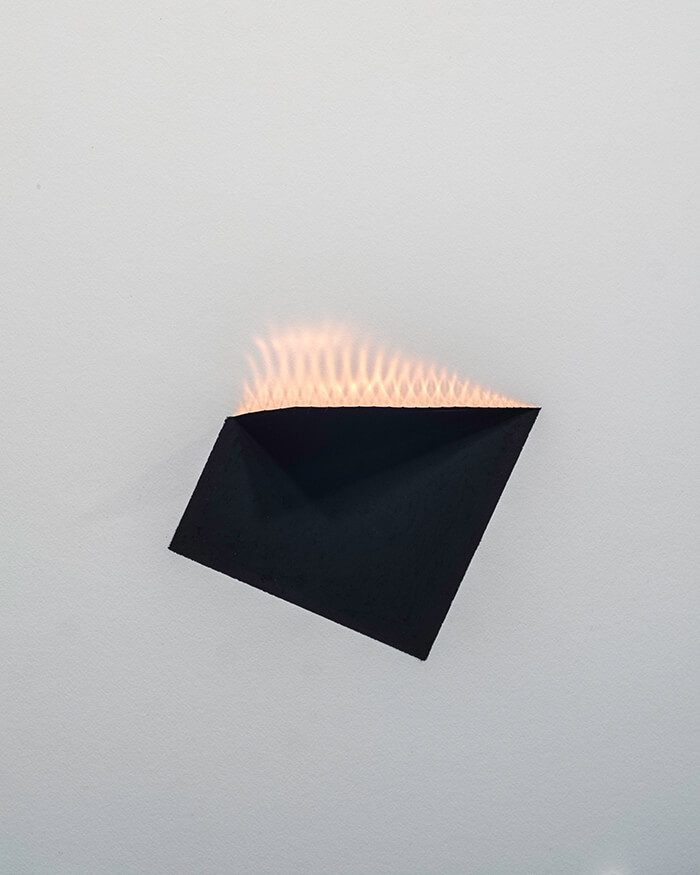

DeJong is a visual tactician, extremely formal in her investigations of the Golden Ratio, but she is anything but doctrinaire. The visual and tactile quality of her drawings and mixed-media reliefs are supremely elegant constructions possessing subtle variations on the shape of squares, triangles, and rectangles often accompanied by finely etched copper lines that glow from the matrix of her dark patinated surfaces. And then there are the copper reflections, like delicate cloud-like blushes, lending to DeJong’s formality a breathtaking fragility. This is particularly evident in three small wall reliefs—square/grid 12, square/grid 6, and square/grid 5, all from 2016. Shapes that at first appear like black trapezoids—each drawn with a conté crayon on board—have at the top a tiny copper “shelf” that is attached at right angles to the board. Each copper extension has a very subtle texture embossed into its surface so that, when each piece is lit properly, an irresistible pattern is reflected from the surface of the diminutive piece of copper to the vertical backing. The reflected light from the copper has a dimensional appearance that is almost holographic. The effect is one of a delicate beauty and this quality lies at the heart of DeJong’s carefully thought out formal relationships that comprise an arc of the linear and the ephemeral.

In effect, DeJong relies on the quasi-mystical reality of the Golden Ratio to guide her constructions, along with the physics of light with its hints of a spiritual component. And the artist’s reliance on a strict geometry is given strength by her enduring intrigue with shadows and reflections—forms that are there but not tangible, existing only by virtue of an imaginative control of all the variables. In DeJong’s vision, obdurate matter—copper, wood, steel—becomes wedded to the mystery of suggestion, coupled with this law: the angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection—as true for the nature of light as for the workings of metaphor.