In Colette Hosmer’s living room, a bookcase contains shelves full of jars of turtle bones, porcupine quills, dead insects, and other sundry specimens the artist has collected from the natural world. Having long informed her sculpture practice, these specimens now inspire a different practice: writing.

Beginning in 2000, Hosmer spent the better part of a decade living and working between Santa Fe and China. While in China to participate in symposia, fabricate work, and exhibit, she also embedded herself in small communities and scoured the markets for materials. Having been thrown a series of curve balls by life a few years ago, Hosmer recently talked to us about her shift from making sculpture to the very different creative process of writing.

Clayton: Tell us about your current studio situation.

Colette: I have a ton of stuff in storage because my mom moved in with me about a year ago, and the whole top floor used to be my studio for 25 years.

I miss it, because I didn’t work intellectually, in fact I tried to make that step aside… I worked with my senses. So I really miss that studio space. I felt like I was kind of starving, so some months ago I went to storage and got some of this stuff out [gestures toward jars of specimens]. It helps to be around this natural stuff again, because I worked with it for so long. I like the creativity of writing, but it’s lacking the… sensual part.

So much of the writing I’m doing about China has to do with the markets and the studios I created there. My art supplies came from the wet markets, open markets, and especially being around the smells, the sights, and sounds. Getting up and going to the market early in the morning to buy my art supplies was a joy. If I was depressed or feeling lonesome once I was there for six months, I’d go to the market and the sounds, the smells, and the energy were just fabulous; I fell in love with those places. So [seeing this] helps influence the writing.

Clayton: How did you transition from your sculpture practice to your writing work?

When I came back from China last time, and had a solo show at Zane Bennett with the work that I’d made there, I got sick and I couldn’t get well. I had Hepatitis C. We figured that it was from a blood transfusion in 1983, so I’d had it over 30 years and didn’t know anything about it. The treatment failed after a year of misery, and then they developed a new drug and I was magically cured in three months. But when I was ready to get back to work again, my fabulous sister was diagnosed with terminal cancer and I moved to Oregon for a year and helped her until she died. Then my mother moved back here with me, and that’s why I have no studio any longer, she’s living with me now, she’s 97. Strong little French woman, she goes up and down stairs a bunch of times a day, beats me at every game.

It’s been a real long transition, but I really feel like I’m surfacing again. You don’t realize you’ve been under water until you come out of it, and you go, “Jesus, that’s where I’ve been the last few years.” These last several months, I was beginning to come to the end of this thing, and now I can feel excited again. It feels strange, because I didn’t realize I wasn’t excited. But now, it’s all coming back. It’s been a couple of detours. I don’t know what kind of road I’m going to be on now.

I’m researching and I’m extremely excited about some remote residencies. There’s one in Florida. It’s this really isolated, remote island, you’re dropped off there and you take care of yourself for a month. You bring your food, you’re on solar, so as the storms come in you might lose the electricity. I love things like that. You just wing it, and it’s a solo deal. Because you don’t know what’s going to happen, that’s what I loved about China so much, you have to roll with the punches.

Clayton: You said that you’ve tried to keep the intellectual at a distance in your practice. Is there a reason for that?

No, I just worked with the materials that I worked with and that inspired me, and the work came from somewhere else, I didn’t intellectualize what I was doing.

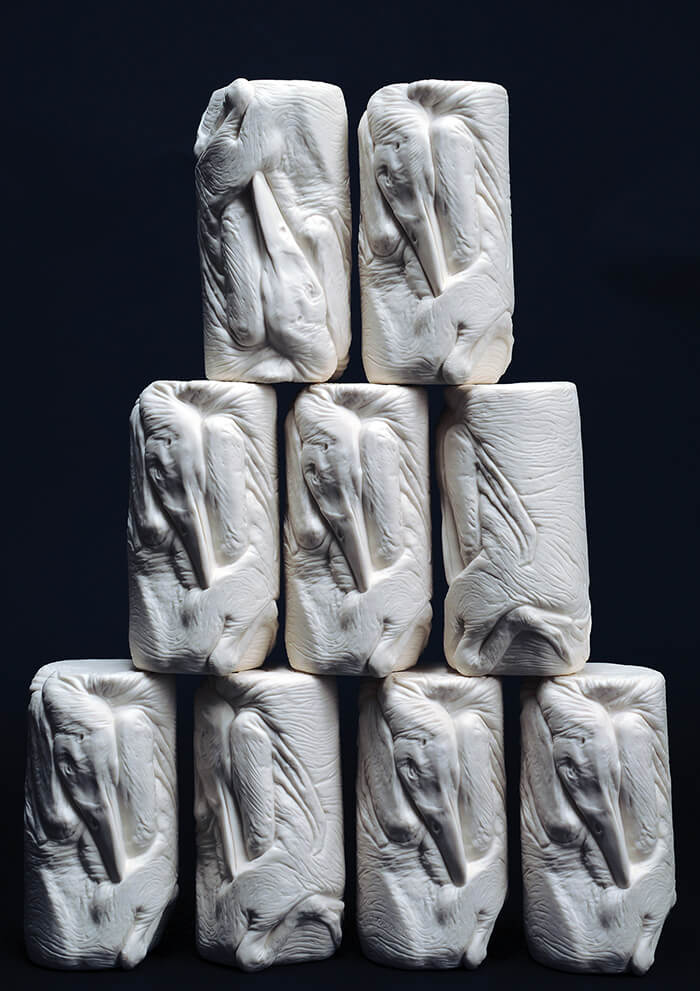

It began with working with fossils. Or making fossils. I had a beetle farm, and they helped me process the skeletons. I love that work, because it was this incredible cycle: the beetles went into four cycles from eggs to larva, the larva grew and grew and did most of the work. Then they would pupate, develop into beetles, and the whole thing would keep going ‘round and ‘round.

A lot of the work I did didn’t result in gallery pieces. I just loved the process. I really thought that contemporary galleries weren’t going to accept this kind of work. I just wanted to do it.

Being interviewed, it was always hard for me to talk about it, because I didn’t think about it in words. And now, with the writing, it’s an interesting progression. I’ve always written wherever I’ve gone because I work in a solo way, so writing is like talking to myself, you know? But it’s always just been journaling, not ever thinking about writing to publish.

Lauren: How long have you been journaling?

Oh god, I guess it started kind of spotty in the seventies. Yeah, pretty much all the way through, and it just became more and more steady. There were various boxes all over the place and a couple of years ago I dug them out and dated them. Now when I’m writing, if I want to revisit a certain period or experience, I know where to go.

It’s really helping with the writing now on China. I wrote everything, and always carried a notebook—good thing, ‘cause I’m older and you forget the regular stuff. If they were interesting, I wrote down conversations and word-for-word dialogue, so it’s fun for me to go back and re-experience some of the best times and have a snapshot to draw from.

Clayton: How do you move the energy of your studio practice into the writing practice you’re in now?

That’s been difficult. Because of what life has offered me, I don’t think I would have made the transition, or been trying to make the transition, if it wasn’t for the illness, and my sister dying, and my mom moving here. I didn’t realize it, but… I’ve been fed, internally fed, for so long with a creative process, that I didn’t realize I was dying on the vine, you know? Aside from all the grief and sadness and pretty intense experiences.

I was nudged in that direction, and I found that the creativity in writing felt good. It surprised me how similar the process was to what I experienced making sculpture. It seemed like a natural direction to go in, and even if I had a studio, I don’t know how excited I would still be about doing body of work after body of work, having show after show, and maintaining that kind of a schedule and lifestyle. I may have been coming to the end of that anyway. That’s easy to say now. If I was still in it, I don’t know.

I loved making the work, but dealing with that other side of it feels more sterile to me. I’m an introvert, so I wasn’t into having all the interviews and getting to be right up front. But it was an important part of it. I totally accepted that and I always understood that 50% was doing the work, and 50% was getting it out there.

Clayton: At what point in your career did you realize that? The 50/50?

Oh early on. I didn’t like it either. I believed it was important to do, whether it came naturally or not.

I never felt like I fit the description of an artist, that was always a struggle. I don’t have an art degree, and I think some of it comes from that too. I started way in the back woods in northern North Dakota, right under the Canadian border; I was born and raised there. Very remote, and 50 years behind the rest of the country, so I had a lot of catching up to do. It was kind of a natural evolution. It wasn’t necessarily planned, on my part.

But then it’s really frickin’ rewarding after [a show] is over (laughs), especially if I felt really good about a body of work. There have been shows that I’ve felt really good about, and knew that came from some place really true, and that didn’t sell worth a damn. That was okay, except for the fact I had bills to pay. But it was okay emotionally and psychologically. Because I knew the work was real.

Lauren: It sounds like your experiences in China were so transformative, what have you taken away from that time? Is that the crux of your writing now?

I realized that I was writing a lot about the exceptional experiences I had there, and I started thinking, I’m not writing a lot about the art that I’m making. But it’s all related, because it was every waking minute. It wasn’t like, now I’m going to do art, and now I’m going to do this—it was all one thing. Because the art is a life, it’s not a profession. It’s a life.

But I’ve started to be able to write more about the art, and to be able to write what I’d never really had words for during a lot of my career, and that’s interesting. Because I’m finding this new expression going from just working with my senses, and having them inform me, to intellectually translating it.

Your question is such a good one, because what I learned about going to China was that I loved spending months in one place, becoming part of the community, working with the people that lived there. I realized I loved living like that because I didn’t have the usual responsibilities and demands that we do in regular daily life here, that I so often find myself moving through unconsciously. For a full day there in China, I was conscious all the time. Really, truly conscious and alert. By the end of the day, I’d be exhausted. The sounds, the smells, the visuals: everything was new, so I couldn’t go to sleep. I was just awake all the time. I saw and experienced more than I ever felt I had the capacity for.

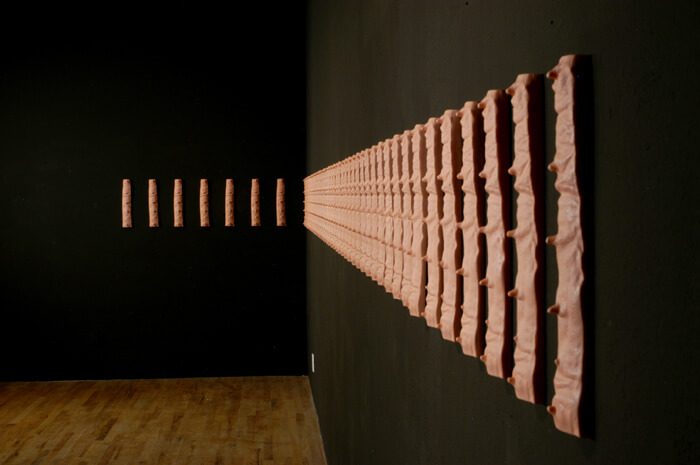

For six months, I lived on an island where there were no cars. I lived in an old villa with cold water, no heat, no air conditioning, I loved it so much. It was just like a bloody struggle to keep yourself relatively clean and fed. I worked in my studio, I’d go to the market, get supplies. I’d sharpen chopsticks sometimes for tools until I could find the right ones, because I worked with clay and plaster a lot. I loved it, that basic kind of work. And it took all day, took all your time, just to work and keep yourself alive.

Clayton: What is the goal with the writing, is it going to culminate in a book?

That’s my lack of planning. Things kind of take their own course, and if I just work, I end up someplace. I’ve gone from short stories to essays, and then I think it should be a book… I kind of go back and forth, but I’m back to the book thing now, starting at the beginning.

Clayton: So you don’t necessarily have an end game with what you’re writing?

No, it’s kind of like with the art. It’s like I’m doing it because it’s food.