Roswell Museum and Art Center, Roswell, NM

July 29 – October 2, 2016

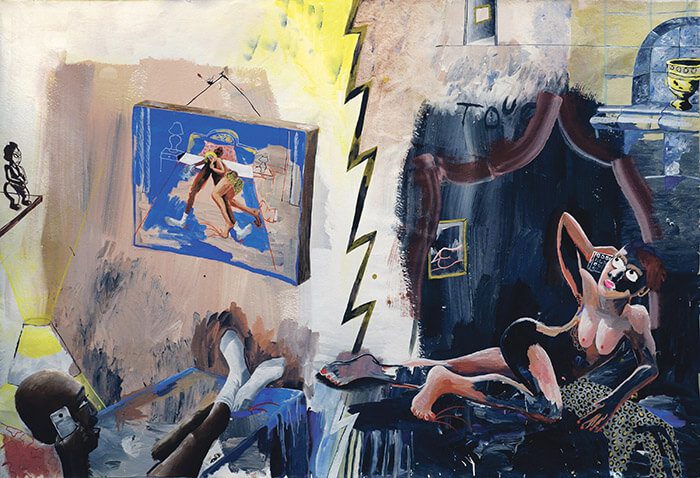

One art critic from the Bay Area, Jessica Zack, referred to Cate White’s work as “vivid tragicomic painting… with its skin-in-the-game vitality” and that is what first hits you—White’s go-for-broke passion for art, life, social justice, and racial fairness. It seems that there is nothing that White won’t investigate and bring to the expressive surfaces of her work: sex, gender issues, literary references, cross-cultural struggles, interracial love, and the history of art. And then there is the energy of her textual zingers that she embeds on the picture plane, zapping the viewers like a vaccination—both infecting them with new perspectives in seeing and helping to cure them of preconceived cultural notions about what is acceptable to bring to the table for consideration. White is not a prude, and she wants to share her unique exuberance with us.

White, who lives in Oakland, received a Roswell Artist-in-Residence Grant to live for a year, fully supported, enabling her to make art unencumbered by the need to make money; and the show at the Roswell Museum and Art Center is part of her residency and its only requirement—to produce enough work for an in-depth exhibition. One of the positive aspects for an artist on the grant is that there isn’t much to do in Roswell except work and be stunned by the light, the expansive views, and the subtleties of the terrain. As all the artists in residence are mature to begin with, they already come to Roswell with a vision and the skills necessary to explore and continue to authenticate themselves as artists. And it is this word “authentic” that comes to mind viewing White’s work—her conceptual boldness, her painterly verve, and her daring crudeness of style that serves her view of herself as an outsider and an iconoclast of cultural blandness.

The light? Our collective history as it passed from the caves of Lascaux to big urban cities to the plains of Roswell? The intangibility of the human condition?

White’s boyfriend Rory is one of the reappearing protagonists in her current cycle of paintings. In one, Rory and Me in a Cliff Dwelling, the two sit facing an opening in a dark cave looking out to the raking New Mexico light and an immensity of space with snakes floating in the air above a faint horizon line. Both the artist and Rory sit in the foreground with their naked bodies at a slight distance from one another as they meditate on—what? The light? Our collective history as it passed from the caves of Lascaux to big urban cities to the plains of Roswell? The intangibility of the human condition? What gives this painting a stab of humor is that Rory has on white athletic socks that he wears in most of the other paintings he is featured in—signifiers of a working-class life, perhaps, but immortalized as symbols of a transcendent spirit where art and life are fused.

There is much to study in White’s large painting The Keys to the City. Not only is this a witty send-up of Diego Velázquez’s famous work Surrender of Breda (1634), it is a tour-de-force image full of erotic tropes, painterly derring-do, an all purpose multicultural joie de vivre, and a zany sense of humor she rarely censors. We come away from this art historical appropriation and ask ourselves: are we on the right side of history? And then comes the question: what exactly does that even mean? In the end, White can only speak for herself about where she belongs and why, but one thing is certain: she is unabashedly polyamorous in her pursuit of painterly goals, and her strategies for the conquest of the canvas aren’t subtle and secretive. White’s is an openhearted lust for artistic adventure—she is one who tilts at windmills like a female Don Quixote. The blades of the windmills are cultural signifiers of great import to White, whether they represent the takedown of white supremacy, working-class heroes, alien space invaders, or a portrait of the artist, her red cape flying behind her, as she rides off into the sunset on a horse with its rich and glossy coat.