Bringing It All Back Home reveals that Patrick Kikut is an unsentimental explorer of the West, manifesting an intrepid curiosity and respect for the land through which he moves.

Patrick Kikut: Bringing It All Back Home

October 28 – December 9, 2023

5. Gallery, Santa Fe

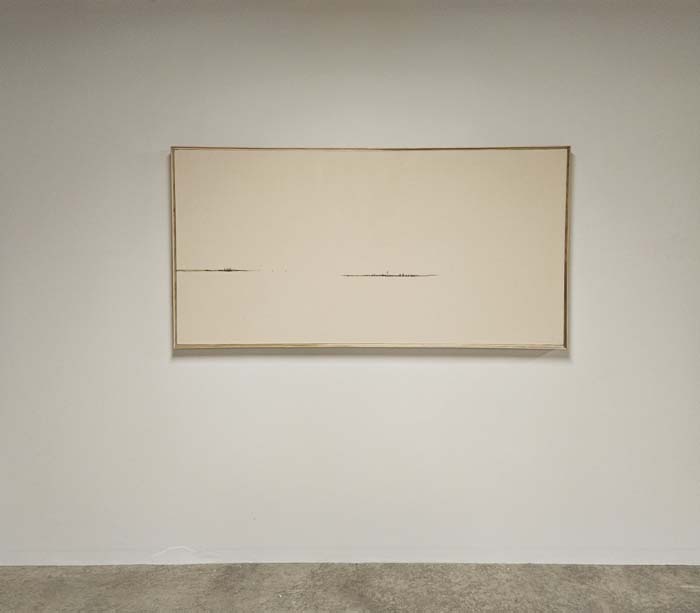

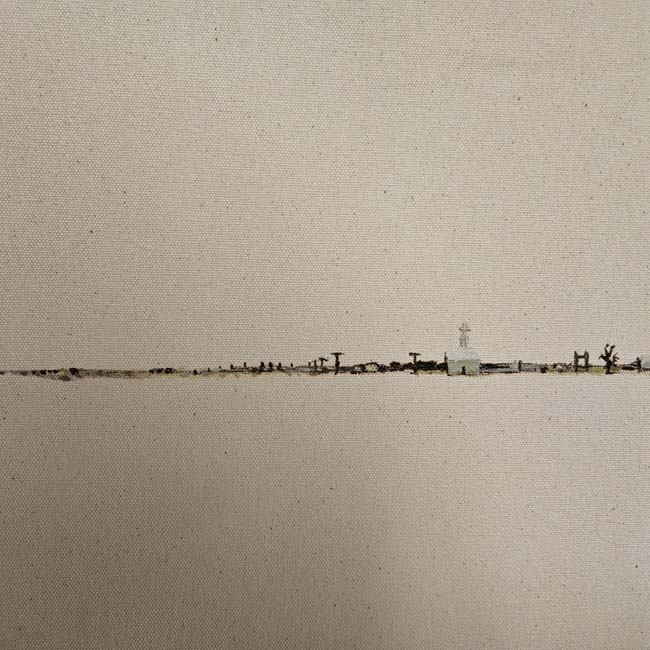

Horizons loom distant and wide in Patrick Kikut’s Bringing It All Back Home at 5. Gallery in Santa Fe. They bifurcate emptiness on paper and canvas and draw the eye to them with a seductive certainty that guarantees your approach.

Prairie Church (2016) is one such piece, occupying a far corner of the gallery as if to suggest your mere presence in the space implies a destination you are moving toward. Like the elusive Point B in Zeno’s paradox, we can only get close, but lucky for us, that is where the magic happens. As with the line that appears to lie on the ridge of a building, separating structure from sky, the horizon doesn’t really exist. Or if it does, it can never be reached. Standing on it is out of the question, unless you are the observed, rather than the observer. The prairie church of the title emerges from the mirage-like horizon at such a tiny scale that the proximity necessary to see it affirms that Zeno was right—you just can’t get all the way there. The piece is from a series titled High Points on the High Plains, in which the high points are barely distinguishable from the horizon that supports them.

With a title borrowed from Bob Dylan’s 1965 album, this anthology exhibition could be said to acknowledge Kikut’s return to Santa Fe, after a seventeen-year teaching gig at the University of Wyoming. Like the potpourri of trout, potatoes, and onion placed on a table in Smoked Trout Stew (2018), from the series Sacrificial Still Lifes, it is a mix. Perhaps the sacrifice in this context is found in a ritual of summing up, hinting at a new beginning.

The Architect (2015) is a small painting occupying the foyer space of the gallery. In it, a lone figure seems to have tentative stature within the implied landscape, simply a band of blue above a band of gray. Its static singularity is matched by the emptiness of the space it occupies. From a series titled Manifestdestination, the piece mutely suggests a frontier space within which the figure seems contained like a piece from a jigsaw puzzle, perhaps entrapped by an imagined destiny. In the main gallery, three paintings from same series, Test – red, Test – yellow, Test – blue (all 2013), offer static mushroom clouds on primary background colors seemingly made pale from the unintended effects of nuclear testing.

The singularity of The Architect is met in the opposite corner of the main gallery by Jack Rabbit (2006), a representation of a hare occupying a space even more featureless than that of its human counterpart in the foyer. The hare is a watercolor of a scanned sticker from a National Parks souvenir store, cut-out and mounted on an oil-based monoprint ambiguously brown. Pixilation from the enlarged scan gives a digitized effect to the rabbit, increasing the distance between subject and object. It is not suggestive of a jack rabbit on the prairie, or even the flash of one in your headlights. This critter is more flickering memory than romanticized portrait.

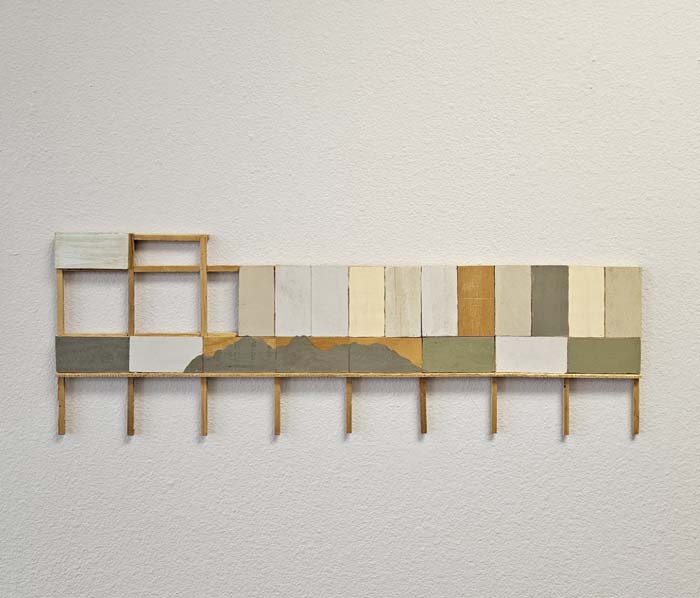

Ridgeline (2012), one of several wall-mounted, model-scale billboard frames that reoccur within the show, features a line passing through two peaks of a ridge. The line is not drawn, but formed by the edges of wooden rectangles representing sheets of plywood as seen on wind damaged billboards that are proliferate along two-lane roads. The mountain ridge represented in this piece is partnered in the same room with Scenic Overview/South Dakota (2017), in which the structure of a roadside stand features its’ own ridge in the form of a beam made of lodge pole pine. In both works, landscape is the peripheral subject, either as seen through a skeletal image in the foreground or as background superimposed.

In another billboard piece, rica (2012), the ghost of the final four letters of the word America reveals the structural metaphor: these scaffoldings are us—what’s left of the country after wind. Again, the lattice-like structure is skinned with tiny multi-hued analogues to sheets of plywood, with a minimalist palette mimicking the weathered surfaces of the abandoned billboards that are its progenitors. In a few years, billboards will have been stalking American roads for two centuries.

Two large portraits of Crow children on the back wall of the gallery bear witness to visitors just as they did on a toothpaste billboard on the Crow Reservation in Montana. Among the last pieces produced in the series Wind Damage, these Crest Kids (2012) were made at the same scale as they appeared on the original sign, though these are handmade duplicates made in the artist’s studio.

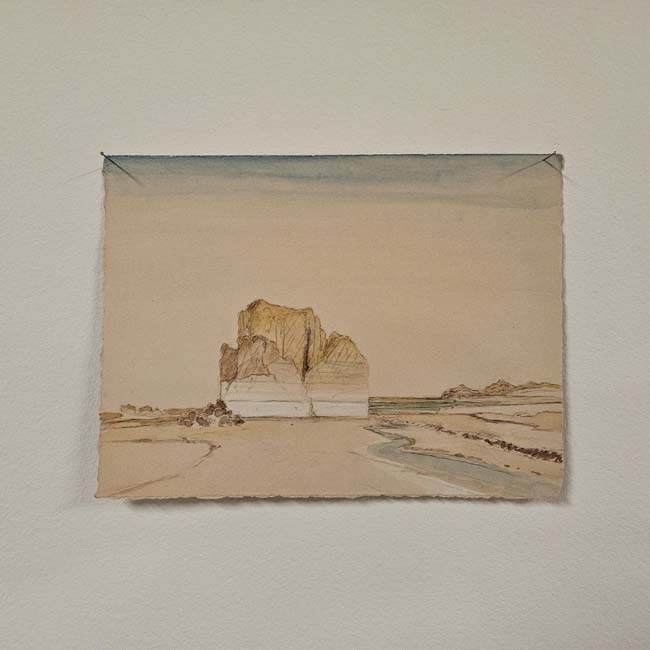

Snowbound Speedboat/Wyoming (2016) is among the largest works in the exhibition and is one of three works from the series Square States and Moonscapes. In it, a trailered boat is further grounded by snow. The quiet and stillness suggested by the image is complemented by the tiny sketch installed next to it. The six-by-eight-inches mixed media field drawing, Long Walk to Lone Rock (2022), requires a lean-in to view it, in contrast to the step-back look required for the much larger sixty-one-by-seventy-three-inch painting, but is just as suggestive of solitude. It is from images collected on a 2019 river trip during which Kikut as the lead artist joined other artists, writers, and conservationists, retracing the 1869 route of John Wesley Powell on the Green and Colorado Rivers. Vision and Place, a book documenting this project and examining the innovations and contradictions of Powell’s expedition in light of climate change and cultural shifts, is on hand to view in the gallery.

Taken as a whole, the works regathered for Bringing It All Back Home reveal that Patrick Kikut is an unsentimental explorer of the West, manifesting an intrepid curiosity and respect for the land through which he moves.