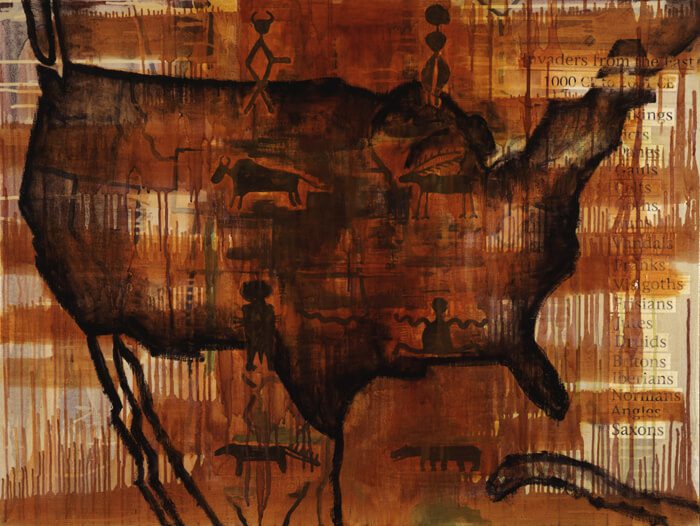

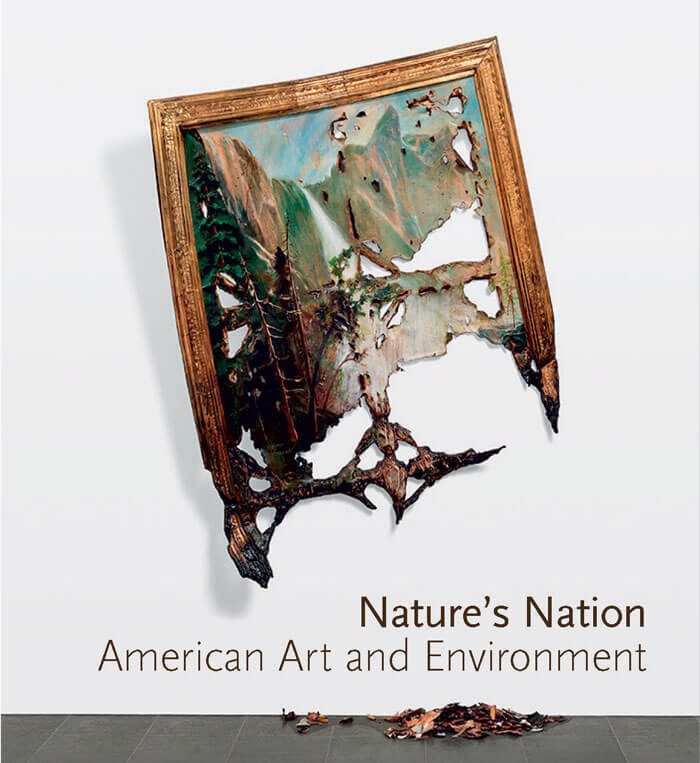

Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment, which catalogues an exhibition that opened last fall at Princeton University Art Museum, proposes a reorientation for American art history around ecology and environmental history. It includes essays by prominent artists and scholars such as Salish artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Anne McClintock, author of the influential postcolonial feminist text Imperial Leather. The monograph also tests the boundaries of its own theories by critiquing artists for the environmental impacts of their materials and creative processes.

In the introduction, curators Karl Kusserow and Alan Braddock call for an ecocritical approach to art history, compelling investigations into the materials and processes of artistic production. They urge us, for instance, to inquire about the toxicity of the materials that go into art-making and how those materials are extracted. They ask us to think about how images are framed, who they benefit, and what labor practices go into their production.

Harvard University scholar Robin Kelsey follows this charge in his essay “Photography and the Ecological Imagination,” stating that photographers and viewers tend to “disregard the material apparatus” that produce photographs. While pulling examples from art history in which photographers make the means of production visible—Lee Friedlander’s Mount Rushmore, South Dakota (1969), for instance, shows the photographer’s reflection in the window of the visitor center—Kelsey accuses University of New Mexico professor Subhankar Banerjee of “suppress[ing] awareness of photography’s participation in our profligate economy.” Kelsey suggests Banerjee’s Caribou Migration I (2002) should have captured a shadow of the aircraft from which he took the image. Rather than aim his critique at the curators who selected this particular photograph and framed it in the exhibition, Kelsey reads Caribou Migration I out of context with the artist’s full body of work, which includes written and photographic representations of the equipment and the labor that goes into production.

If capitalism distracts us from “the reality of production,” as Kelsey argues, one way it does so is by representing ecological crises as products of discrete individual choices made outside the social and political discourses that maintain capitalist modes of production. In other words, blaming Banerjee for photography’s role in the economy is like blaming a factory worker for all the plastic straws in the ocean. What Kelsey’s critique reveals, then, is a potential flaw in ecocritical thought: the failure to account for the discursive roles of the observer (himself) and the distributor (the museum) in the production of nature and nation.

This oversight notwithstanding, Nature’s Nation provides an important reorientation for American art history by setting ecology as the material basis for social and political critiques of capitalism. The curators offer the book as one example of how to proceed, and, with the urgency of our times, they encourage other scholars, critics, and artists to take it further.