Foto Forum, Santa Fe

February 23 – March 26, 2018

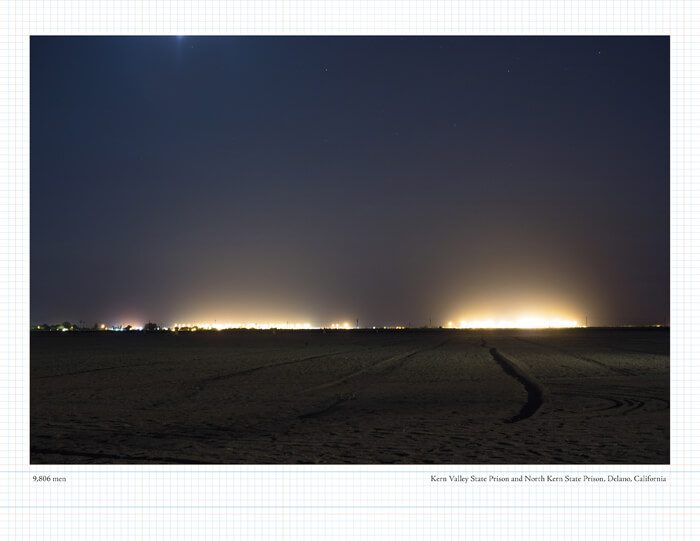

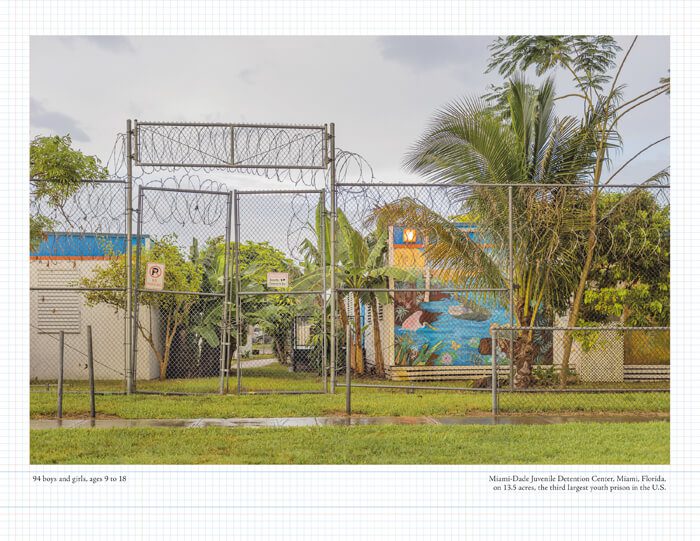

“Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality, understood as recalcitrant, inaccessible; of making it stand still,” Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography. Although she isn’t referencing prisons themselves, they are continually a reality which is systematically hidden from the public view. Sontag was right: reality can be inaccessible, which is also true of the geographical placement of prisons. They are often situated in order to sanction, hide, and isolate the incarcerated. They function as an ideology, a tool to render inmates invisible.

It’s this uncharted territory that Ashley Hunt—an artist, photographer, and professor—has spent the last eight years traveling the U.S. documenting. During this time, he captured over two hundred and fifty images of the prison industrial complex, detention centers, and jails. Foto Forum, a new gallery in the Santa Fe Railyard, has eloquently situated his findings in a solo exhibition, Degrees of Visibility. Upon arrival, the viewer is met by an industrial-esque floor with dozens of photographs. Yet the power of this exhibition lies not in what it claims, but what it poses. It asks us to consider a landscape free from the architecture of penology, a prison-free state.

Photography has the capacity to generate a visceral documentation of reality, and Hunt’s photographs—all of which are subtle in color and poetic in composition—demonstrate the control of the penal system. The photographs create a liminal terrain of transparency for the public to consider the ideologies and constitution of its institutionalization in a wider context. These photographs demonstrate doing time neither as past nor present (which often defines photography) but instead as authentic, alluring, and anthropological. The photographs are accompanied by short descriptions of where they were captured, reminders of the geological separation between each place. They are not devoid of context; they seek to create an ambient sense of reality.

But how to present penological structures through the medium of photography? Rendered on graph paper like a series of field notes, some of the photographs feel as though they are in motion, which reflects Hunt’s methodology of uncovering a penal system so static and hidden from view. A photograph on the back wall, Old Atlanta Prison Farm, resides in a limbo state. The viewer first asks: is this a workspace, shed, or large outhouse? On closer inspection, the caption describes the history of the 1,248 acres purchased in 1917, then closed in 1995 and abandoned. The building is no longer inhabited by persons, but instead plants—reimagined as an environmental placement of growth, life, possibility.

Such intricacies of information manufacture the exhibition as intrinsically political, in which art can allow us to become visible, recognized, and acknowledged. By bearing witness to the architecture of criminality, Hunt curates a visual archive which otherwise wouldn’t exist. The meditation between what isn’t known, and indeed can’t be claimed, is the space we as viewers find ourselves subject to. The abandoned prisons act as a time lapse, a glimpse into a space which used to function and be inhabited. But these images aren’t solely concerned with inaccessibility; they are political, empathic, and carefully orchestrated.

Degrees of Visibility examines the architectural restraints and organization of criminals, as opposed to the intimate lives of those incarcerated. The buildings often appear forgotten, subject to neglect, not only due to their isolated placements but also their design and panopticon surveillance. In these photographs, reality flickers, and we presume that Hunt and the places he documents reside in a reimagined context of their own. But his political agenda is subtly apparent, too. Wooden boards are scattered throughout the gallery on the floor, with print-outs from activists’ prison-abolishment groups. One references Black Lives Matter, another depicts “Resistance.”

These collective traces infuse the project with political weight. But what we are left with, or are asked to ponder, is the means by which Hunt captured these images. His journey demonstrates an important conceptualization of where prisons are often situated: the abject space—which is inherent in their organization and ideology. Hunt’s proposition is limitless and poignant; it prompts us to reconsider sectors of society hidden from view—interpersonally and culturally—and to contemplate them in their aesthetic, socio-political entirety.