One of the most difficult things for an artist to do is to reckon with her own legacy. This is not just a theoretical concern for where one fits into a particular historical narrative—it’s also of material importance. What does one do with all the “stuff” that has accumulated over time, the sketches, the letters, the receipts, the photographs? An artist may destroy all of her correspondence, working notes, or even artworks themselves, out of a belief that they are not significant to posterity. But posterity, like that old cliché about history, is determined by the winners—or in this case, by those whose lives leave evidentiary traces in the form of an archive.

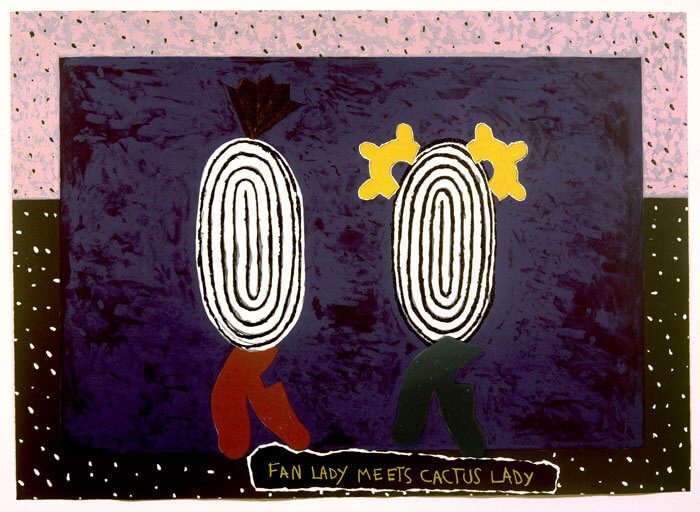

Archival materials have the potential to disrupt or reroute the flow of history. Artist, curator, educator, and writer Harmony Hammond was well aware of this when she began thinking about where to place her collection of “between five thousand and six thousand slides of work by other artists: mostly lesbian feminists but also straight-identified feminist artists, historical work by women artists, and a few slides by male artists (mostly gay or queer-identified),” which she had collected during her seventeen years as a teacher and while writing her book, Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History (Rizzoli, 2000). Hammond had amassed these slides “to supplement slide libraries at universities and art colleges and art books, all representing a white male heteronormative history of Western art.” Knowing that her collection could upend the art-historical canon, she set out to find a home for the slides and other research materials she had collected, and the vast archive related to her decades-long art practice.

To Hammond, the stakes were clear: “Until the 1970s, women and lesbian artists had no history. Without a history, you don’t exist. We are missing from the art-historical narrative. If we don’t find ways to not only make and present our work, but to document it, to preserve the work, and rewrite existing histories, we too will be erased, and I refuse to let that happen.” After sending out inquiries to several archival institutions across the U.S., all but one of which were interested in both those materials documenting contemporary lesbian art and those relating to her own artistic practice, in 2015 Hammond chose to place her archive with the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles:

I made a political decision. While I support small special-focus libraries and archives, given the nature of my papers, I felt it was important to place them within a major archive of American art, thereby inserting feminist/lesbian/queer artists into the larger history and narrative of American art. At the Getty Research Institute, my papers joined the collections of modern and contemporary artists’ papers, including those of the Guerrilla Girls, Suzanne Lacy, Faith Wilding, Carolee Schneemann, Yvonne Rainer, Barbara T. Smith, Mary Kelly, Robert Mapplethorpe, and other feminist and queer artists.

Hammond’s deliberation and her determination to place her archive in an institution where it is properly preserved, publicly accessible, and among other feminist and queer materials is a perfect case study for how an artist might begin to grapple with her legacy. Through her research into contemporary lesbian art, she was able to identify a major lacuna in the history of art, and she was able to make a contribution to begin to fill that gap.

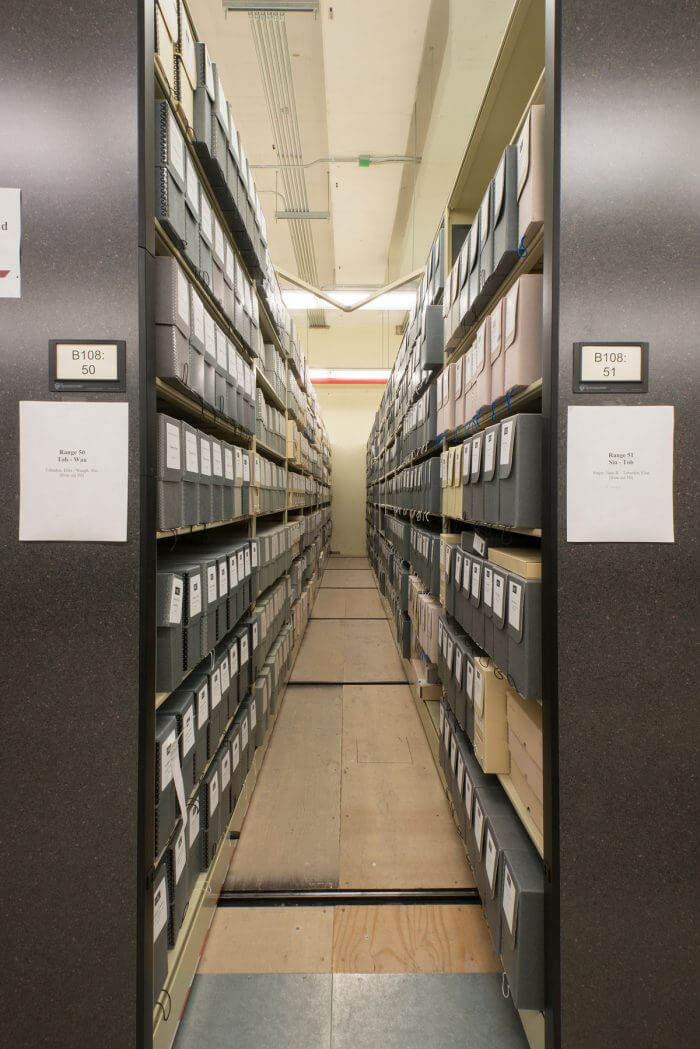

Absences in the archive are just as important as what appears within it. At the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, a large humanities research center with holdings of rare books, manuscripts, photographs, art, and personal effects, Andrea Gustavson is the head of instructional services. She works to create curricula for faculty and graduate instructors who wish to teach with the collections. Working with archival materials in the classroom offers opportunities for students to learn about the construction of history—that history does not emerge fully formed but is the product of a series of choices, not only about what gets included, but who gets to write that history in the first place:

If I structure the class right, I save time at the end for the students to talk about what’s in the room and what’s missing from the room. I’m getting them to think about identifying historical gaps, absences or silences in the collection. That opens the floor for a conversation about the fact that I have selected these sources and there is labor behind the processing of them, that there are decisions that go into the acquisition and preservation of them. I ask them what I should go looking for next year, and if I can’t find it, why could that be?

There can be many answers to that last question, and what those answers might be is the crux of how collecting and preserving archival materials contributes to the understanding of history. As Gustavson explains, one of her main goals when discussing absences within archives with students is to get them “to understand that some historical records may never have existed; or if they did, then they weren’t saved; or if they were saved, they weren’t preserved; and if they are preserved, then maybe they’re not accessible.” These layers of creation, preservation, and access lie at the heart of what archives do: they try to carry the material evidence of the past forward and to make them available… forever.

The intensity of this goal, this theoretical forever, can often make archives feel uninviting. As Carolyn Steedman has noted in her book, Dust: The Archive and Cultural History (Rutgers, 2002), “atmospheric conditions in the Public Record Office, being at the optimum for the preservation of paper and parchment, are rather cold for human beings.” But there is another, metaphorical coldness that forms a common assumption about the archive—that it is a place of calcified history, a monolithic bastion for the historical canon.

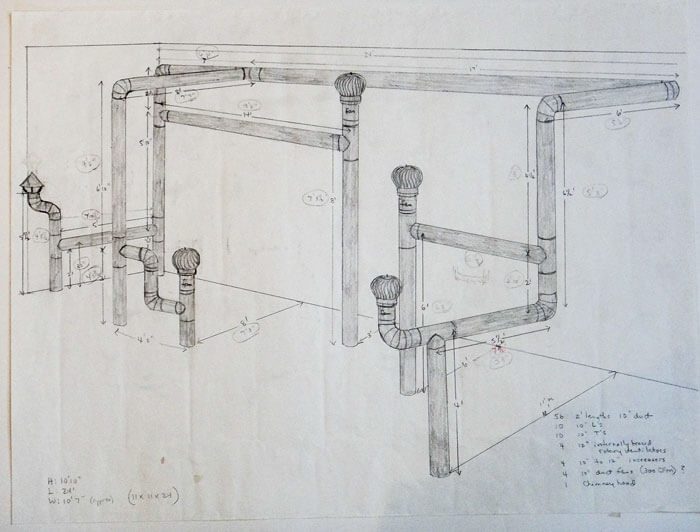

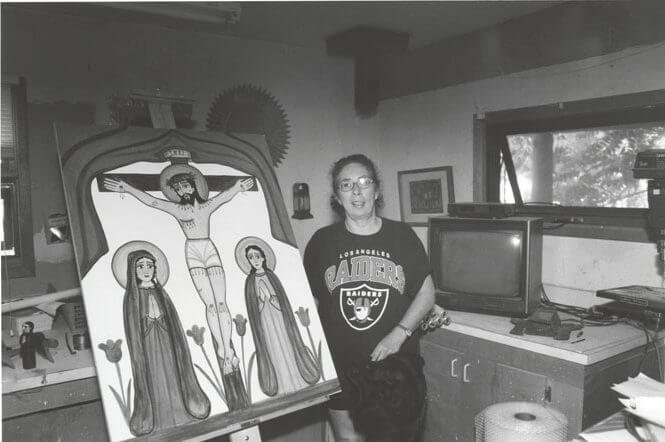

Many archival institutions are striving to combat this idea by expanding their collections. At the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C., highly specialized staff work to identify and acquire personal papers and institutional records that broaden the idea of what is “nationally significant” in the history of American art. Josh T. Franco, as the Archives’ national collector, has plans to augment the collections in several subject areas. One is santerismo, the Mestizo-Hispano tradition of carving figures of saints: “We have, just by the numbers, the largest collection of artists’ papers and records [in the U.S.]…. We have Abstract Expressionism covered. Conceptualism and Minimalism we’ve got. But santerismo we don’t have covered as well.” Through his research, including in materials donated to the Archives of American Art by New Mexico collectors Chuck and Jan Rosenak, Franco has been in touch with several New Mexico artists, including Marie Romero Cash, who recently donated a sketchbook and a series of sketches to the Archives of American Art. Through Franco’s work on santerismo, he is building new connections among materials already in the Archives’ collections, as well as supplementing them with more significant holdings.

The work that archivists, educators, and artists do to preserve and provide access to archives is, as Hammond makes clear, political. It is also highly personal. Sifting through the evidence of one’s own history can be a daunting process, and it can be difficult to know how or where to start. Franco offers some practical advice to artists who are thinking about what to do with their own archive. First, an artist shouldn’t worry so much about whether her materials are organized correctly. For the Archives of American Art (as with other institutions), the order in which an artist arranges her materials, as idiosyncratic as it may be, is of as much interest as their content. Franco also suggests that artists visit their local university or other special collections library to see what sorts of materials archives collect. And finally, Franco advises, “Don’t throw anything away.”

This last dictum might seem overwhelming to anyone with limited space and is thus, again, political: even saving one’s own materials is imbricated with issues of class and other sociopolitical factors, and those with the means to preserve are those whose collections ultimately end up in institutions. Andy Warhol famously chucked all his office detritus, anything from half-eaten food to mail to financial documents, into a cardboard box each month and had it shipped to a storage facility in New Jersey. Not many artists have the ability to hoard so extravagantly. The artist Tom Martinelli, archive and digital resources manager for the Holt/Smithson Foundation, who worked with artist Nancy Holt to organize and preserve items related to her artistic practice ranging from photographs, sketches, journals, receipts, and other paraphernalia, is well aware that Holt’s ability to hire him was a key factor in the maintenance of her legacy (Holt passed away in 2014). But he also sees something else at work in an artist’s decision to think about the future:

For me, part of it comes back to coming to grips with the value you place on yourself or don’t place on yourself. An artist can always give a list of things to do once they are no longer around, but the process is deeper than that. It gets into personal psychology, what you know of yourself, how well you think of yourself projected into the future, how you think of your past. Every artist has to figure it out for themselves—you’re on your own, figuring out what’s really important and what are the gems of your own history. Nancy knew the value of her work.

Holt had the foresight, most likely from the time she spent preserving and promoting the legacy of her husband, Robert Smithson, to understand that the materials that accumulate as an artist lives and creates work have value—so she saved them.

And this brings up another issue: we can’t really know where we fit into history. Professional archivists understand this. Their job is to catalogue, arrange, and preserve materials, and to describe them as objectively as possible. Interpretation is the job of those who conduct research, whether they be scholars, other artists, or amateurs. And those interpretations can veer onto unexpected paths. Martinelli recalls, “The Smithsonian has a bunch of Bob [Smithson]’s tax documents. And a particular historian went through Bob’s expenses and made certain assumptions that Bob was seeing a shrink, which Nancy thought was so funny. She just got a kick out of that. This is what can happen. People extrapolate stories.” The line between the personal and the professional can often blur within an artist’s archive. For Martinelli, there is a separation between Holt’s work and her life, and he sees his role partly as a steward of Holt’s attitudes regarding that distinction:

We were very good friends, so I can represent some of her point of view of things. The story about Bob’s expenditures and imagining a therapist is an invention out of the artist’s control. At Holt/Smithson Foundation, we make decisions with Nancy in mind, and that includes her privacy.

I’ve never understood [the] total separation of an artist’s life and her art. It’s impossible. The boundaries between art and life are blurred and entangled. That said, I do think the artist or writer should have a say in what is made public. (I recently destroyed a batch of very old and embarrassing love letters!) The fetishizing of “celebrities’” possessions can get pretty nauseating, and the archivist, working with the artist, has to consider a delicate balance between information and invasion of privacies.

The thought that one’s love letters may one day see the light of day in a historian’s book or article may be enough to prompt some artists to relegate all of their personal items, or items which may seem to them to have little research value, to the bonfire. It’s important for us to remember that we don’t know, that we can’t possibly see, all the ways in which items of the past might come to inform the history of the future. Franco offers an example of how personal items can provide important context for an artist’s life:

Andres Serrano’s papers have his natal charts, and, in Lucy’s papers actually, there are Julie Ault’s letters to Lucy where she did crystal readings on Lucy’s behalf and then gave her the breakdown of the analysis and told her which crystals she should have with her and why. Ault is associated with gritty New York activism, and Serrano is associated with his bodily fluids and really striking portraiture, of course from Piss Christ but also the homeless series and the KKK series. Those materials that show an underlying interest in the occult in the art world, that don’t necessarily show up in the artwork itself, are really fascinating and something only the archive can offer.

Lippard, who notes that neither she nor Ault remembers those letters, points out, “in the ’80s, Julie’s crystal reading[s] were not seen as incompatible” with her artistic practice. This is a fact that could easily be lost after generations, just as we have so little evidence of the ethos of past cultures whose records of everyday life are not extant.

There are countless anecdotes such as this that emerge from archival research. These minutiae are, ultimately, what make history rich and varied, rather than monolithic and exclusionary. There is much evidence, too, that archival materials are already facilitating new histories. Martinelli foresees a new generation of scholars and artists who will get to know Holt’s work once her papers become accessible (the logistics of that access are still in process). Gustavson, who witnesses each semester the experiences of the over eight thousand undergraduates who learn about archival materials for the first time, describes some as “shimmering with excitement, because they have figured out something that really nobody has put together yet, and they are understanding how scholarship gets made, how history gets written, how cultural studies arguments are significant.” And Hammond, whose focused goal was for her archives to represent a heretofore invisible chapter of art history, says of her efforts, “While not yet fully catalogued, the Getty Research Institute reports that the papers and images in my archive are already being viewed and utilized by many art historians, curators, teachers, and other artists. A huge ‘burden of representation’ off my shoulders. Mission accomplished.”