Moab Arts Reuse Residency program in Utah, which attracts worldwide artists to make pieces out of rubbish, challenges the concept of detritus and trash.

MOAB, UT—Moab has a citizenry of about 5,000 with a population of three to five million, if you count the tourists.

This statistic is often measured in dollars but could just as easily be demonstrated in pounds of waste produced annually. Moab’s waste management department estimates that tourists generate close to 20 percent of the trash that ends up in its landfill.

The irony of this, of a place so magnetically gorgeous accumulating the detritus of every passerby who comes to revel in its desert splendors, was not lost on the Moab Chamber of Commerce in 1986 when it dubbed Moab’s landfill “America’s Most Scenic Dump.”

In the spirit of this cheeky superlative, the city funds the Moab Arts Reuse Residency, a one-month program where artists are invited from around the world to create works of art using Moab’s trash.

“I think trash is a really interesting reflection of a place, especially here,” says Melisa Morgan, associate director of Moab Arts and Recreation. “It’s extremely abundant due to the nature of our community because of the tourism. I think the program incites a conversation about how we use resources here.”

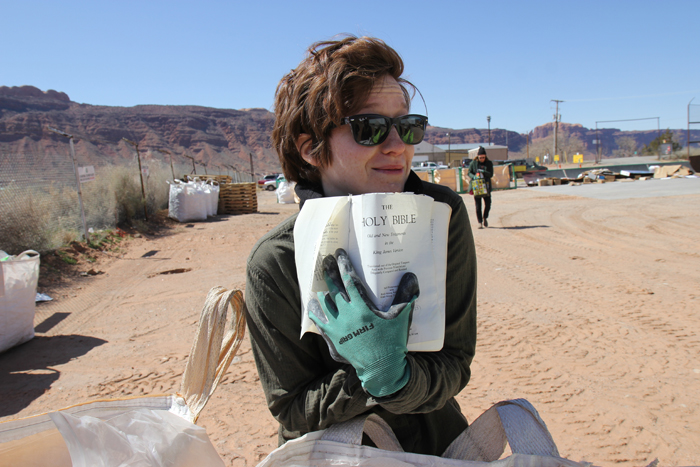

During their stay, artists are encouraged to re-evaluate how they source materials through direct engagement with the Canyonlands Solid Waste Authority. Through this partnership, artists have access to materials at the recycling center, the landfill, and the local thrift store, WabiSabi.

Last summer, Moab Arts hosted Justin Tyler Tate, an installation artist and fabricator who often works with recycled materials. He created a twenty-foot-tall play structure titled Track & Trail out of reclaimed wood and tires.

“Everything was recycled except the screws,” Morgan says, including the bike-powered lighting system that illuminated the structure.

On his website, Tate writes: “Track & Trail seeks to not only generate culture, but also power, turning that which is seen as waste (in terms of time spent playing as well as discarded materials) as that which is able to give life to society.”

Most recently, the residency hosted Noémie Despland-Lichtert and Brendan Sullivan Shea, the Brussels-based designer-architect duo who make up Roundhouse Platform. Much of their practice centers on sustainable construction, and they used the residency as an opportunity to draw inspiration from many of the region’s lauded natural builders.

“For such a small community, there’s such a density of different types of people and different kinds of intelligence that are crystallized in the community,” Shea says. “It’s been really productive for us to tap into those streams of knowledge and incorporate that into our outlook as designers.”

Morgan says she intends for the residency to grant artists the time and space to develop new ideas that they can later apply to their typical practice.

“It’s really difficult to produce something super concrete when you’re only here for four weeks and you don’t know what materials you’ll find,” she says. “In my mind, the program is much more about the process and having the freedom to see what’s possible.”

Shea and Despland-Lichtert were inspired by the 1,500-pound bales of cardboard at the recycling center. “We like the idea of using compressed waste material as building blocks for larger construction,” Despland-Lichtert says.

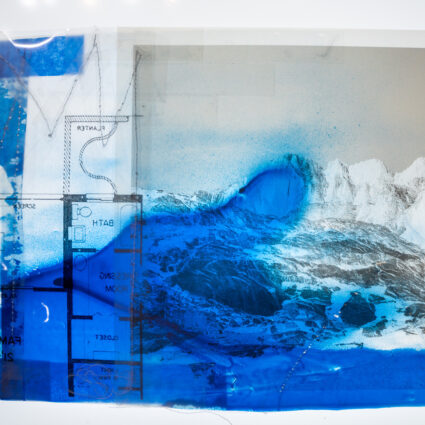

The duo used the residency to delve into some conceptual work comparing the stratification of Moab’s famous geology to the stratification of the landfill, research they outlined in a zine titled Pre-Cretaceous / Post-Consumer. Much like the history of deep time, they posit, a contemporary history of the town can be read in the layers of its trash.

This year, Moab Arts hopes to host a total of four artists, pending budget approval from the city and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. The Moab Arts Reuse Residency offers artists a $1,000 stipend and free housing.

“I think the best thing art can do in a community is act as a lens for seeing something differently. I’m not sure that our community lives with an awareness of the amount of waste created here due to the nature of our economy,” Morgan says. “We want to bring in artists who can give us a fresh perspective on our situation and what’s possible.”