“You’re really good at real—real is your second nature…”

—dialogue from the film Teknolust

Who was Roberta Breitmore, and how does she figure into the vast body of work by the artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson? Roberta Breitmore was never “real,” even though she was made of flesh and blood; her persona was, in fact, just a figment of Hershman Leeson’s feminist imagination, only more developed than most artificially created alter egos that are set loose in the art world. The documentary images of the fictive person in the Roberta Breitmore Series (1974 to 1978) were my introduction to the work of Hershman Leeson. Breitmore, although a fictional creation, was an attractive blond who had her own apartment, advertised for roommates, went to a shrink, was photographed extensively, and had her own driver’s license. As a feminist art project, Breitmore anticipated Cindy Sherman’s penchant for dressing up in costumes and photographing herself hundreds of times in her project Untitled Film Stills, from 1977 to 1980. That said, if Sherman’s one-off still images of herself as invented women characters have become legendary, I wonder why so many people have blank looks on their faces when the name of Lynn Hershman Leeson comes up in conversation regarding the world of contemporary art. Her science-fiction-y movies alone, Conceiving Ada (1997) and Teknolust (2002), feature no less than the extraordinary actress and quick-change artist Tilda Swinton. Both of these movies—along with several other of Hershman Leeson’s wondrous films—were recently screened at SITE Santa Fe in conjunction with Future Shock, the inaugural exhibition at SITE’s re-designed space in which Hershman Leeson also has an installation, Infinity Engine (2017).

“The artist goes on a journey, not of self-discovery, but of self-recovery, and her amazing self-possession is bolstered by the uniqueness of her visions and her phenomenal technological expertise with which she brings those visions to life.”

Hershman Leeson wrote all of her own scripts, and she directed and produced her films as well, bringing to the screen not only her innovative computer-science fantasies—anticipating our current digitally dominated world and obsession with artificial intelligence—but she has made documentaries as well: Strange Culture (2007) brings to bizarre life the twisted story of artist Steve Kurtz and his arrest by the FBI for being a would-be bio-terrorist. And there is the fabulous overview of the Feminist Art movement in the film !W.A.R.—!Women Art Revolution (2011), as illuminating as any movie could be about the forces that ignited a dynamic constellation of artists, scholars, and activists who finally inserted themselves into the art historical continuum. But the film that establishes and solidifies Hershman Leeson’s ground zero as an artist, poet, and visionary filmmaker is her autobiographical work First Person Plural, the Electronic Diaries of Lynn Hershman Leeson (1996).

As a moving-image memoir and deeply disturbing confessional, First Person Plural covers the years 1984 to 1996 when Hershman Leeson was grappling with her emotional scars and the psychological blowback from a childhood of physical and sexual abuse, followed by a period in her life as a battered wife who, with her daughter, eventually found the courage to walk away from that situation. “First Person Plural” is an apt phrase to speculate on the trauma of an abused person who often undergoes a psychic splintering in the effort to survive shocking realities. Hershman Leeson reveals herself in her documentary as multiple projections of a central self, but not in the sense of being a schizophrenic—i.e. someone who has lost touch with the Plane of the Real and proceeds to live on an Imaginary Plane peopled by distinctly separate personalities. All of Hershman Leeson’s fragments, if you will, are of a piece—integrated into the whole of a woman with astounding creative powers. Although Hershman Leeson presents herself, over the span of twelve years, as a woman undergoing a painful transformation of great significance, she never loses control of her imaginative mind, her genius loci, and its transcendent function as her raison d’etre. The information she shares is indeed devastating—a child who has her nose broken by a broomstick; who has her head set on fire; who has to suffer “visits” from a pathological father; who is physically hurt by her first husband—but so strong is Hershman Leeson’s creative drive that it ultimately provides the energy for her profoundly moving, fascinating, intensely colorful, gorgeously illustrated, sometimes humorous, and always philosophically challenging films.

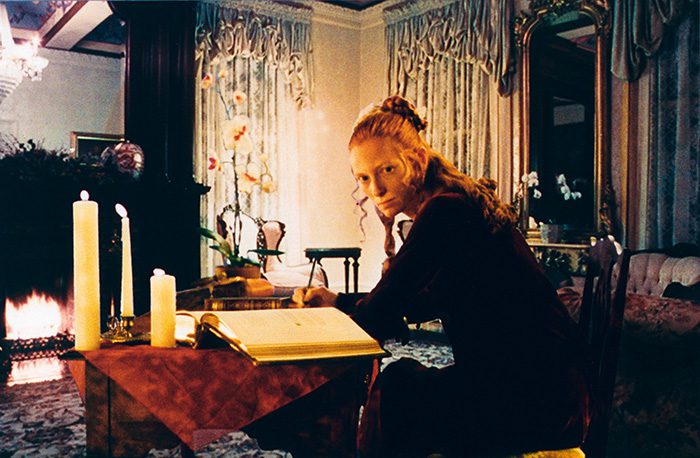

It has to be said that in Hershman Leeson’s movie-as-memoir, never for an instant does she traffic in histrionics, self-pity, or a sense of pushing the boundaries of truth to serve a set of artificial psychological constructs. The artist goes on a journey, not of self-discovery, but of self-recovery, and her amazing self-possession is bolstered by the uniqueness of her visions and her phenomenal technological expertise with which she brings those visions to life. Hershman Leeson proceeds from the world of her dreadful personal secrets—compounded by the history of the Holocaust that she deftly interlaces into her own story—and emerges as a revelatory genius with an affinity for strong, productive, creative, and individualistic movers and shakers, giving them a voice and animating their lives in a series of brilliant, thought-provoking movies. In particular, Hershman Leeson has embraced women who have stories of their own to tell—the feminists of !W.A.R., for example, or the nineteenth-century Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace, a daughter of Lord Byron, brought to life in the film Conceiving Ada (1997). Ada Lovelace, as she would become known—and played by the luminous Swinton—was both a product of her society and a pioneer mathematician and writer, as well as collaborator with Charles Babbage, working with him on his mechanical computing machine. It was Lovelace, though, who published the first algorithm intended for this “Analytical Engine,” helping to develop seminal ideas about the mathematical language necessary for coding machines that would become the prototype for twentieth-century computers.

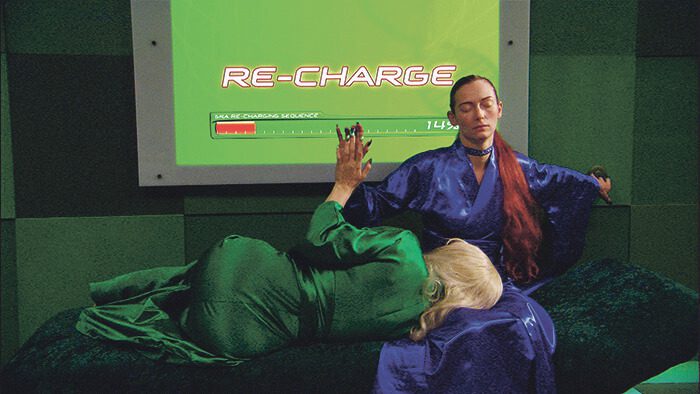

If the construction of Roberta Breitmore was a thread from Hershman Leeson’s prolific store of alter egos, so was the computer scientist in the movie Conceiving Ada, the fictional Emmy Coeur, who creates a cybernetic bridge to resurrect the character of Ada. Coeur brings Ada back to life by transmitting some of her own DNA, by way of zeroes and ones. The re-creation of Ada is far fetched, we know, but in the context of a movie made twenty years ago, what seems a huge stretch is now just the tip of an artificial-intelligence iceberg that is floating in an ocean of computer simulations and heading toward your own front door. To say that Hershman Leeson is prescient doesn’t even begin to tap into her utterly charismatic mindset. Following by only five years on the heels of the story of Ada Lovelace—and Ada’s belief in the power of numbers to manipulate machines so they can, for example, create repeatable patterns and make music—the film Teknolust (2002) provides a visual glut of the ravishing Swinton playing cyborg triplets—Ruby, Marine, and Olive—as well as playing the role of the computer scientist Rosetta Stone who invents them. Make what you will out of the name that Hershman Leeson gave to the nerdy and wily scientist Rosetta Stone. That would be a whole other article.

Teknolust is rigorously stylized, gorgeous to look at, funny, and in the end, a vision of “replicants” who at first suggest some computer invention run amok; yet, in the last analysis, the simulations morph from futuristic icons into creatures of flesh, spirit, soul, and moral wisdom, laced with a sense of humor. And the chameleon-like Swinton dominates nearly every frame—larger than life and embodying the notion of the imperfect nature of perfection. She has charisma to burn. Swinton also has a role, though a much smaller one, in Hershman Leeson’s documentary Strange Culture; she plays the late Hope Kurtz, wife of artist Steve Kurtz, the latter accused of being a bio-terrorist. Strange Culture is a brilliant quilting of real events and individuals who are at first played by actors; then the real individuals on whom the story is based make appearances as the odd and tragic events continue to unfold surrounding the arrest of Steve Kurtz. The story blossoms in all its convoluted weirdness in the realm of a conspiracy theory embroidered out of nothing—at least nothing illegal or remotely terroristic. The final section of the movie depicts the actors and the real individuals together, discussing the evolution of Kurtz’s narrative and how it might eventually be resolved in the courts, short of sending him to prison. What set everything in motion in Strange Culture was (1) the premature death of Kurtz’s wife, Hope, due to natural causes, and (2) the FBI’s misinterpretation of artistic research into genetically modified organisms. They asked: how could THAT possibly be art?

The viewer enters the film as if into a labyrinth of speculation: What is art? Who gets to decide what art is and what it couldn’t or shouldn’t be? What is the way that science is done? Should artists cross over into scientific terrain to make work that is inscrutable to an uninformed public?

As part of an artists’ collective called Critical Art Ensemble, Kurtz and his wife were putting the finishing touches on an installation to be shown at Mass MoCA in 2004. One of the aspects of the installation was an investigation into cultures, legally purchased, of genetically modified organisms. However, right before the artists were to install the exhibition, Hope unexpectedly died in her sleep. Kurtz called 911; the medics arrived, as did the police; they took a look around; they saw all the scientific apparatus and petri dishes filled with “powders”; they confiscated Hope’s body; and then they arrested Kurtz for possible murder and for being a potential maker of weapons of mass destruction.

Strange Culture seesaws between outrageous presumptions and the nightmarishly possible. The viewer enters the film as if into a labyrinth of speculation: What is art? Who gets to decide what art is and what it couldn’t or shouldn’t be? What is the way that science is done? Should artists cross over into scientific terrain to make work that is inscrutable to an uninformed public? What is the nature of the real, and who gets to test the waters of artifice positioned on the fulcrum of an artist’s vision?

In some form or other, these questions weave in and out of Hershman Leeson’s practice as an artist and a filmmaker of great imaginative depth. In addition, her work is fed by all the digital and technological shadows that flicker against the walls of her mind and the foundational experiences of her childhood. In her expansive world view, the personal becomes the cultural, becomes a refractory mirror of the time we live in with all its nuts and bolts of coding, iterations, simulations, information theory, feedback loops, and the transition from orderly states to disorderly ones. Hershman Leeson has envisioned the overlap of the human and the artificially intelligent and what that could possibly mean for a meta-narrative of our own pluralistic lives.

Like the serpent that bites its own tail, I loop around to the word charisma and its original meaning. It comes from the Greek and means a gift; it also means to favor, to possess a divinely inspired grace or talent, as for prophecy and healing. If the charismatic shoe fits, let the artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson wear it.