A-Z West, Andrea Zittel’s decades-long art experiment presently stewarded by High Desert Test Sites near Joshua Tree, investigates the architecture of everyday life by stripping items to their most basic components.

JOSHUA TREE, CA—Andrea Zittel is hard to pin down. The galleries that exhibit her work want to call her “an American artist… whose practice encompasses spaces, objects, and modes of living.” The architects and designers that reference her work like to repeat a quote of hers from 2015: “It’s impossible to talk about art without talking about design.” It’s clear to me that she’s all of those things—an artist, a designer, an architect—and then some. In my mind, the best thing about her is the moment you think she’s one thing, her work shatters expectations. Perhaps the one resounding question that brings together all of her various projects is one she set out to answer at the beginning of her career: “how to live?”

It’s a rudimentary question, as straightforward, at first glance, as questions like “how to walk?” and “how to talk?” And yet, buried beneath its surface are the many complex relationships between humanity’s need for freedom, security, autonomy, authority, and control. For this reason, it makes sense that Zittel has conceived of her own work as a “life practice.” If that life practice is a stethoscope, the heartbeat of society is the sound she’s listening for.

Questions on the periphery of her singular inquiry like “what do you need to live?” immediately branch off into “how much is too much?” and “what can you do without?” In a way, that cascade effect might be the best way to make sense of Zittel’s vast and eclectic body of work. Each of her projects represents a souvenir collected along the way, as she’s descended further into the rabbit hole of one expansive question.

Long story short, all of this was buzzing around my head when I toured the pioneering project that first drew the San Diego native into the desert twenty-three years ago: A-Z West.

Stewarded by High Desert Test Sites since 2022, A-Z West is a lot of things. At first, it was a five-acre parcel of land—originally homesteaded in the 1950s—on which sat a two-room cabin Zittel rebuilt to serve as a “home away from home” and studio in 2000. Over the years, the project has grown to eighty acres that include several additional homes, an office and workshop, a guest cabin, shipping-container workshop spaces, a chicken coop, a garden, a classroom (the list goes on).

Walking between different areas, there were moments when I felt like I was wandering around an obscure summer camp, hidden away in the rain shadow of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains. The dusty roads connecting one building to another, open-air firepits, and jackrabbits scurrying out of sight made the whole space feel like an only semi-tamed wilderness. When peering into individual structures, however, I felt like I was walking into a Minimalist painting.

Zittel’s experimental project, tucked into the rocky hills looming over Joshua Tree, California, claims to encompass all aspects of day-to-day living, such that “home furniture, clothing, food all become the sites of investigation in an ongoing endeavor to better understand human nature and the social construction of needs.” Jonathan Griffin wrote for Cultured that Zittel’s work “is intentionally designed to align with a unique mode of existence that draws on Modernist utopianism, contemporary environmentalism, and progressive self-sufficiency.” But what does all that look like, in the flesh?

Simplicity. Simple, geometric patterns; bare, unadorned surfaces; the most basic possible relationship between utility and design.

“When you remove the things from your life that you don’t need, what’s left?” posed Zittel while gazing out at the sprawling Mojave desert. It was late in the morning, so the sun was bright and the air cool.

Perhaps the best representations of this reductive approach are Zittel’s A-Z Wagon Stations (2004). A reference to the covered wagons that journeyed across the western frontier, these sleek, simplistic pods are built to easily collapse, transport, and reassemble. No larger than the footprint of a twin-sized bed, the pod-like structures feature all the bare necessities, including a small curtained window, a shelf, a mattress, and a large, curved door that opens skyward like the backend of the family van.

Sitting inside one of them, I wondered—besides air conditioning, perhaps—what would I really miss, if I were to move into one of these? The first word that came to mind was “space.” Room to think, room to pace, a door to slam when I’m angry, a variety of spaces whereby I might compartmentalize my already constrained work-from-home life. The second words: “indoor plumbing.”

When it comes down to it, the last question we vaulted-ceiling-obsessed Americans ask ourselves when it comes to shelter is “what don’t I need to live, really?” We amass, we collect, we expand, we consume. Compulsively, without thinking, culture-wide: “more” is the word constantly on the tips of our tongues.

“It’s not necessarily meant to be a comfortable experience,” Zittel tells me. “Living like this, even for only a few days—it puts everything into question.”

Of course, you can’t help but question your life out in the desert. Whether you live in a quiet suburb or a bustling city center, spending any amount of time in the blankness of the desert is a shock. It’s like somebody shut off the music you’d been listening to your entire life and replaced it with vapid silence. In a way, Zittel’s work has that exact same effect.

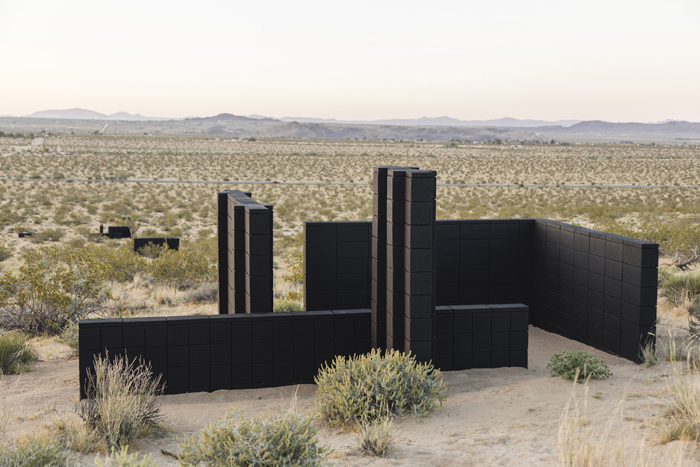

Planar Pavilions (2018) represent this feeling best. When examining the permanent public works with the rough and rocky hills in the background, each of the ten Planar Pavilions’ walls appear like the skeletons of structures under construction. Though none of them have roofs, their series of vertical planes function enough like a division between outside and inside that they might even be called homes. From the opposite perspective, however, with Twentynine Palms Highway immediately in the background, semi-trucks bumbling toward town, these semi-structures feel like ruins.

“Ten years ago, none of this was here,” Zittel tells me, pointing at the twinkling lights of the faroff city. “I’m really interested to see how the meaning of this place changes, as Joshua Tree continues encroaching up this road.”

I’m interested, too. In fact, that observation makes me want to return to A-Z West every year, just to revisit each of its paradigm-shaking micro projects to see how time inevitably changes them. How will the effects of climate change challenge this experiment? As summer temperatures rise and winter storms worsen, will the Wagon Stations one day be entirely unlivable? Will Joshua Tree eventually develop these wild hills? Will this investigation into the architecture of daily life mean anything, once we run out of resources with which to build new things?

“As someone who lives and works in Andrea’s designed spaces every day, I allow myself to answer that question—‘how to live?’—within every small act of experience,” says HDTS administrative coordinator Hannah Bartman. “Sitting at a desk, drinking a cup of tea—the question of ‘how’ eventually turns into ‘why.’”

I can think of no better way for the question “how to live?” to evolve, as future generations pick up where Zittel left off. After all, why live life the way we do? Why not rethink absolutely everything?