The music plays. Suddenly the words feel right. It makes perfect sense. The Norse god Odin is crossing a rainbow bridge into the castle in heaven. That’s one way of reading it at least. The recording switches off. Discussion resumes. A college professor hovers over a giant textbook, consulting a gloss of dead languages. The origin of a key word is debated. Another interpretation of the phrase is advanced. It’s a typical Saturday morning and Adam Harvey’s reading group has nearly concluded their weekly session with Finnegans Wake.

It’s unclear whether James Joyce’s notorious final book can be called a novel at all in the customary sense. It uses an invented language and largely disregards conventions like character and plot. The text contains scrambled fragments of dozens of languages and seemingly limitless quotations from the most obscure possible sources. The uninitiated reader will easily dismiss it as illegible gobbledygook. Members of Harvey’s group, however, insist that it is worth reading despite these difficulties, meeting every weekend like clockwork to soldier through its enigmatic pages.

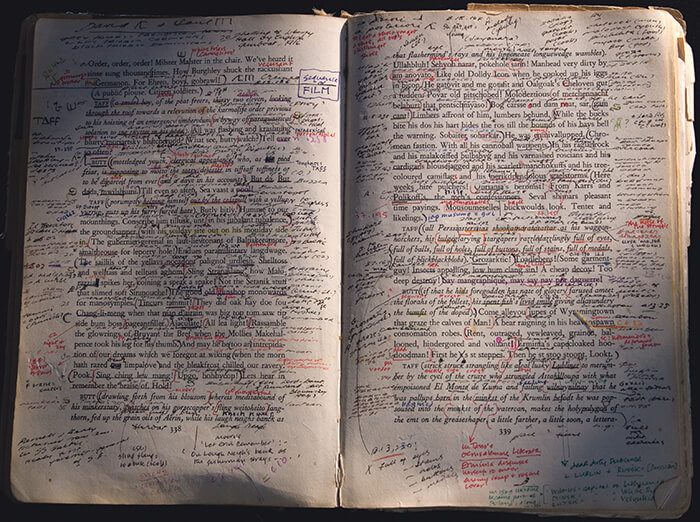

I joined the Joyce group at St. John’s College where over the course of a few hours we carefully read through a difficult page-and-a-half of Joyce’s penultimate novel Ulysses before attempting five rather grueling sentences of Finnegans Wake. Group regulars arrive equipped with stacks of reference material to collaboratively decipher these idiosyncratic books. This approach is especially useful when reading the Wake, where each line has multiple meanings and may require a full page of citations to understand. The book’s opacity rewards repeat readings and careful study, an attribute which has made it a literary cult object for nearly a century, bringing groups of readers together to compare notes and swap cyphers. Now more than ever, the internet has created a global enterprise of Wake scholarship and facilitated a passionate subculture around the book. Harvey’s group in its current form has been picking at this lexical Gordian knot for seventeen years. They’ve just recently cleared the halfway point.

Reading Finnegans Wake is not a task to be completed. It’s a subject to which scholars devote entire careers. “You’ve never really finished,” Harvey explains. The interminable project of decoding the Wake is reflected in the book’s structure, which has no clear beginning or end. “There is no capital letter at the beginning of the first page. There is no punctuation mark at the end of the last page. It would be appropriate to bind Finnegans Wake on a Rolodex and begin reading at any point in the text.” The book is a timeless enigma. The text itself is a recursive Ouroboros, wrapping back on itself. Its carefully crafted mystique encourages obsession and has created fan fervor seldom seen in literature.

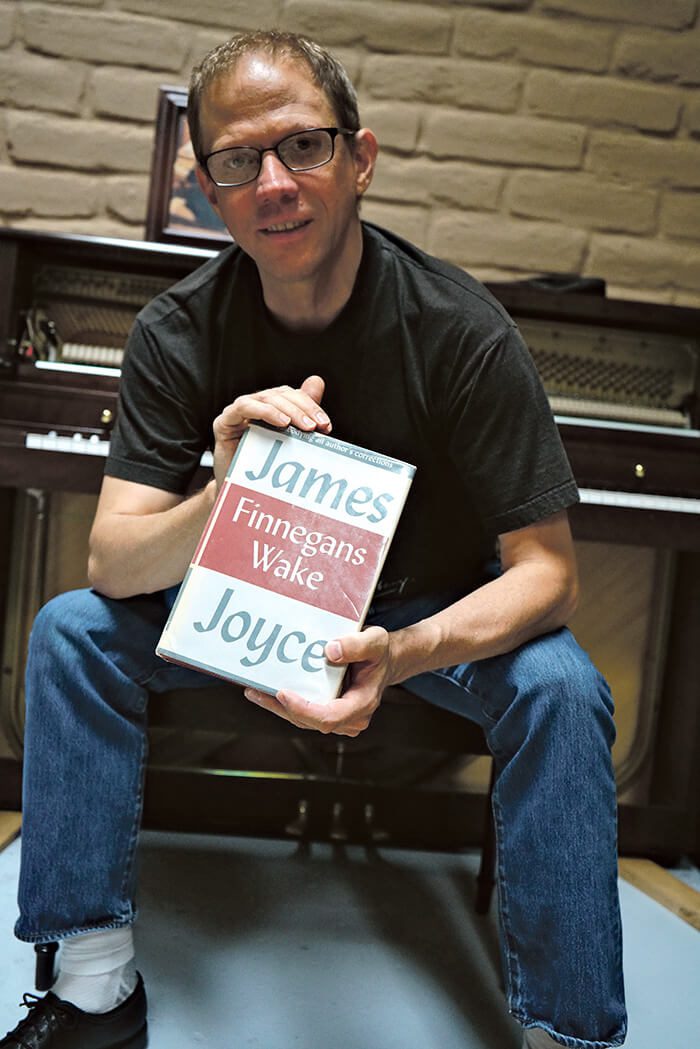

Harvey attained notoriety in Joyce circles as the guy who could recite entire chapters of Finnegans Wake from memory, a feat which he has been performing publicly for sixteen years. Trained in theater, he started memorizing passages from the book as monologues back in the early nineties when Blue Moon Books & Video was still renting Joseph Campbell lectures on VHS tape. “It was the ambition of an arrogant young actor,” he recalls. “I thought that I would be a sorcerer and that sparks would fly out of my fingers.” Years later, Harvey has played to venues around the world and even without digital pyrokinesis, his stage adaptations have been warmly received in Dublin, Trieste, Edinburgh, New York and beyond.

Harvey knows how to evoke the magic of Joyce’s language. His performances benefit from the years of study he has invested in understanding the multiple meanings of each word in the text. The Wake is essentially made of puns and the right intonation is essential to understanding the joke. Over the years, Harvey’s stage show has evolved to include an illuminated projection of the text which allows the audience to read the words as they are being recited. Presented in this way, Harvey renders Finnegans Wake an (almost) intelligible and elegant work of living language.

“I don’t know if I could perform Finnegans Wake again without music… Working with Mike’s music changed my entire perspective on how it should be done.”

SETTING THE WAKE TO MUSIC

The studio is serene. The acoustic padding on the ceiling removes any unnecessary noise. Light filters from the skylights. Harvey leans over a computer screen, examining a blue waveform. He consults a notepad and reads a number: “The next cut will be at twelve minutes two seconds point seven nine six.” The engineer grins and says, “You’re a very organized young man!”

Clips of the final mix come from the enormous monitors. First the hypnotic bass track plays solo. Then a pause. Then Adam’s voice enthusiastically bounces out of the same monitors. Then another pause. Then both tracks play simultaneously.

Harvey and the studio engineer Jono Manson are mastering Harvey’s album-length collaboration with punk rock legend Mike Watt. The recording is part of the online audiobook project, Waywords and Meansigns, which pairs readers with musicians to set selections of Finnegans Wake to music. For this installment, Watt’s original bass score accompanies Harvey’s recitation of Chapter 7, a passage he is well acquainted with as a performer.

Any collector of punk and hardcore records knows that Mike Watt’s band Minutemen was a pivotal arrival on the Los Angeles scene at the outset of the eighties. The band was the first recruit to Black Flag’s SST Records, a prestigious label which went on to release a veritable who’s-who of indie music in subsequent decades. After the untimely death of the Minutemen’s guitarist in 1985, Watt went on to found several other groups. Harvey saw one of these in 1990, an amalgamation of ex-Minutemen called fIREHOSE. “That night was amazing,” he waxes. “Everyone was thrashing and bumping in a frenzy of mutual enthusiasm. For that night, I became a true mosh-pit millionaire.”

Mike Watt is hard to get on the phone. I wasn’t able to grill him about Finnegans Wake, but the experienced reader will notice Joyce’s fingerprints in the titles of Watt’s songs. The Ulysses tribute “June 16th” appears on the Minutemen record Double Nickles on the Dime. There’s also the fIREHOSE track “Up Finnegan’s Ladder,” a punk rock plot summary of the famously plotless book. Watt is allegedly the kind of guy who interrupts band practice for trips to the public library. His literary side appears in solo albums inspired by academic subjects ranging from Dante’s Divine Comedy to the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch.

Watt and Harvey’s composition for Waywords and Meansigns is a joy to hear. Watt’s bass track is minimal and contemplative, advancing slowly and complementing the lyricism of Joyce’s words. Harvey’s performance highlights the storybook quality of the chapter and finds natural momentum in the undercurrent of the music. The final piece alternately showcases Watt and Harvey’s talents, allowing each to shine during musical interludes and vocal solos. It is a faithful adaptation, successfully evoking and enhancing the musicality of Joyce’s linguistic extremism.

“I don’t know if I could perform Finnegans Wake again without music,” Harvey tells me. “Working with Mike’s music changed my entire perspective on how it should be done.”

Since director Derek Pyle started Waywords and Meansigns in 2014, the project has grown to include readers and musicians from all over the world. “Adam and Mike are just one part of a project that involves a couple hundred people,” he tells me. “We have people from Berlin, Amsterdam, Japan, Poland, and the UK. We would never be able to do a project like this without the internet. In the 20th century, when you needed a record label to put out your music, you would never have found someone willing to put out sixty hours of stuff in a made-up language.”

Waywords has much looser parameters than similar internet-based adaptations like Plymouth University’s Moby Dick Big Read, which paired visual artists with readers like Tilda Swinton and David Attenborough for every chapter of Melville’s whaling epic. Pyle’s project takes a more free-form approach, embracing the experimental, non-chronological spirit of the source material. This approach seems entirely appropriate for a book so dependent on reader interpretation. “Joyce invented his own language to write this book, so there’s no wrong way to read it,” Pyle explains.

Watt and Harvey’s forthcoming contribution will complete the second edition of Waywords, which will soon boast two separate recordings of Finnegans Wake in its entirety. Like the Wake, however, Waywords and Meansigns doesn’t stop when the book ends. The project will continue into its third edition, allowing successive performers to discover new meaning and new music in a book that can never be finished.

Information about Adam Harvey’s weekly Joyce reading group can be found on his website, joycegeek.com.