In this essay, nicholas b jacobsen braids together ongoing histories of Mormon and U.S. settler colonialism and genocide against Nuwu and Diné peoples at Pipe Spring National Monument and Lake Powell.

In the desert, there’s a spring. For thousands of years, Kai’vi’vits Nuwu families (Kaibab Southern Paiute) have cared for this water. They talked to it, farmed with it, and drank from it. In the 1870s, my cultural ancestors built a fort on top of that spring and cut the Kai’vi’vits off from it. After a century of settler-colonial control, the spring’s visitors are now warned: “DO NOT drink the water.”

The sandstone fort now stands as a monument to Mormon pioneer fortitude. The National Park Service calls this fort “A Story Built in Stone.”

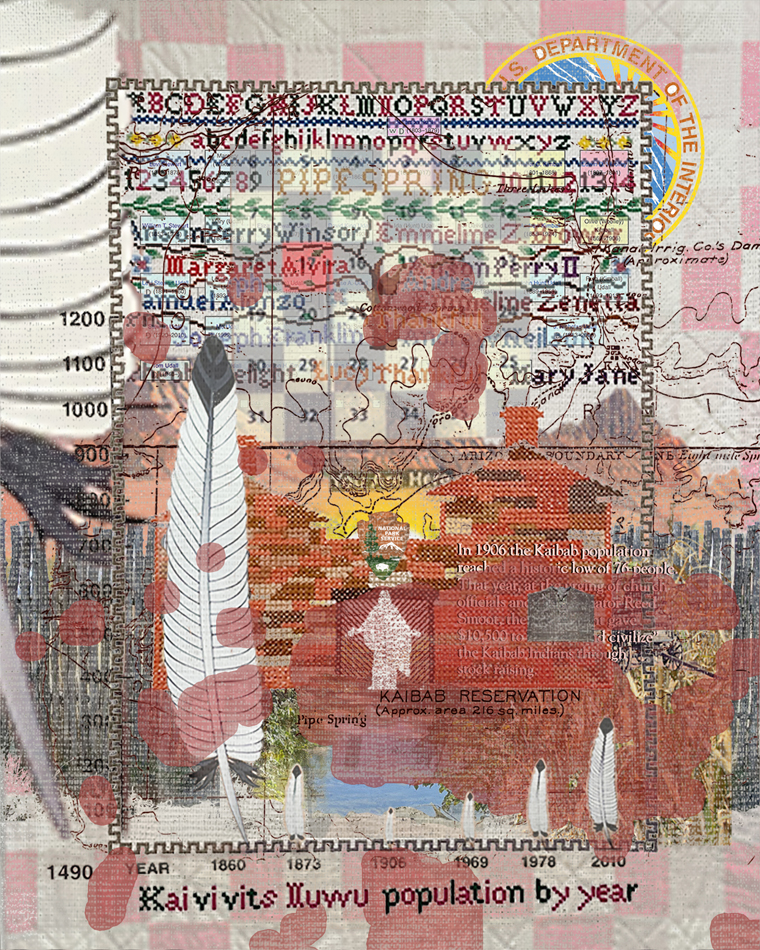

But the stones’ stories are quite different. Unlike the Department of the Interior, they don’t frame this genocidal occupation as one of “conflict and compromise.” Their stories are explicit in the ways these pioneers stole and occupied Nuwu homes, lands, and waters. The Kai’vi’vits, who’d already been grieving the loss of ninety percent of their people killed by Spanish diseases and enslavement, buried another ninety percent of their family members as Mormons drove them to starvation.

Forty-four years after Matungwa’va (Pipe Spring) was stolen by Mormons, the U.S. returned it to the Kai’vi’vits as part of the Kaibab Paiute Indian Reservation designated about sixty miles north of the Colorado River. Sixteen years later, at the behest of a prominent Mormon family, the U.S. took Matungwa’va back and rendered it a National Monument. This family, the Heatons, were made supervisors of the Monument and continued to live on and profit from this stolen land and water, just as Mormon families had since 1863. Though the Kai’vi’vits are legally entitled to a third of the spring’s water, after 160 years, they still have no access to it.

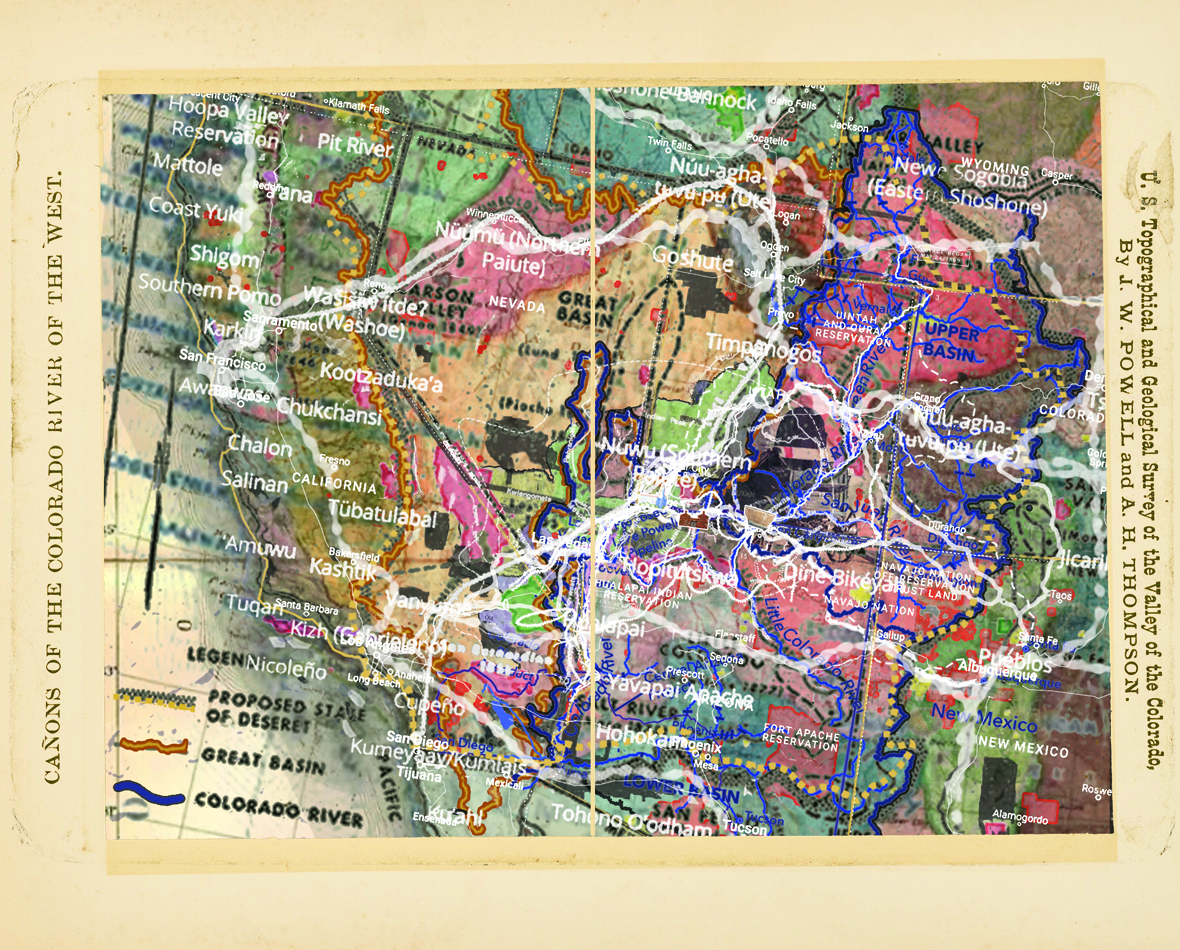

This spring of truth is a tributary of a broader history of the colonization of the Colorado River. From the 1870s, when John Wesley Powell headquartered his Colorado River mapping trips at Pipe Spring fort, to the 1950s, when Mormons and the U.S. brought Powell’s dual goals of damming the Colorado and assimilating Indigenous peoples to fruition—these fluid histories continue to flow into our desiccating present.

Powell’s recommendations for large-scale reservoirs were based on his observation of Mormon irrigation practices in these arid lands. Similarly, Mormon doctrines shaped the Department of the Interior’s Tribal Termination and Glen Canyon Dam projects.

Mormonism teaches that the peoples Indigenous to this continent are among the descendants of a group of white, ancient Israelite immigrants who were cursed “with a skin of blackness” after they apostatized from Mormonism. These cursed peoples are later promised that when their descendants, who are said to be contemporary Indigenous peoples, assimilate to Mormonism, they’ll be made again a “white and delightsome” people.

U.S. Senator Arthur V. Watkins, a practicing Mormon from Utah, wrote the U.S.’s 1953 Tribal Termination legislation and was a major supporter of the Glen Canyon Dam project.

In a letter to his Mormon Church leaders, Watkins expressed his belief that Tribal Termination, meant to strip federally recognized tribes of their reservations and federal support, would “help the Indians… become a white and delightsome people.”

The next year, Senator Watkins defended the Glen Canyon Dam project in Congress against the Sierra Club by quoting Genesis and testifying that the U.S. is “following the commandments of God” by building this dam.

Manifest Destiny never ended. The religiously justified, federally supported colonization of Matungwa’va destroyed Kai’vi’vits Nuwu lives and lifeways. The religiously justified, federally enacted tribal termination policies, though it was rescinded after three decades of court battles, destroyed what little land and sovereignty tribes had left. The religiously justified, federally enacted Glen Canyon Dam and flooding of Lake Powell destroyed miles of Nuwu and Diné farmlands and water access.

Just as the Kai’vi’vits are still cut off from Matungwa’va despite being legally granted access to it, the Navajo Nation’s access to the Colorado River has been limited despite holding primary rights to the water since 1868.

In December 2020, after eighteen years in court (and after suffering some of the highest rates of infections throughout the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic due in part to a lack of water access), Utah finally settled with the Navajo Nation, granting them 81,500 acre-feet of water access. Three years later, after a twenty-year-long court battle with Arizona, the settler Supreme Court determined that although it is the U.S.’s treaty obligation to ensure recognized tribes have water, they don’t have to do it anytime soon.

About an hour west of Matungwa’va is the so-called Saint George valley. Here, Mormon pioneers built another set of sandstone walls over a Nuwu spring. The Saint George Latter-day Saint temple, with its red-stone walls washed white, stands as another monument to Mormon pioneer fortitude. The cattle that grazed on Matungwa’va’s grasses fed the laborers who built Saint George and its fortified holy house. Through their theft and occupation of Nuwu lands and waters in the Saint George area, my ancestors starved the Tonaquint, Paroosit, and Ua’ayukunant Nuwu to extinction.

A century after this temple’s construction, I was raised in that valley. Today, Saint George is “America’s fastest-growing city” and is running out of water. But then, so is every other city and farm dependent on the Colorado River watershed, which is perhaps why the U.S. and its states are in no hurry to ensure Indigenous Nations have access to these waters.

Pipe Spring Fort was built to defend my ancestors’ genocidal occupation of Kai’vi’vits land and water. Pipe Spring National Monument continues to serve this same purpose. Once we didn’t need these forts to exert our dominance physically, we made monuments and memorials to defend our dominance ideologically. We set our versions of history in stone and buried the rest.

But buried histories act as springs do. Held by the earth, they rise in offering to those who know how to care for them and listen to them.

May we, too, be held by the earth, that we may know, listen, and care.