LewAllen Galleries, Santa Fe

January 26 – March 16, 2018

Tucked into a quiet nook in the northwest corner of LewAllen Galleries’ rather showy structure is a gem of an exhibition. Quest for the New: Modernism in the Southwest features artworks by a who’s-who litany of Santa Fe’s early twentieth-century art colony, from Cinco Pintores members Josef Bakos, Fremont Ellis, Willard Nash, and Will Shuster to Taoseños Emil Bisttram and Andrew Dasburg; and the furthest-flung of all of them, John Sloan, a New York painter who would become known as a key member of the Ashcan School.

Curated by the gallery’s director of modernism, Louis Newman, with able assistance from Victoria Addison of Addison Rowe Fine Art Gallery, the exhibition provides evidence for Santa Fe’s significant contributions to the grande dame herself, American Modernism. (For the purposes of this article, by “Santa Fe” I mean the entire population of artists who spent time in northern New Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century. I have an abiding horror of the term “Southwest” when it comes to art and will refrain from using it again here.) The artists who arrived in the teens and twenties and moved into the Canyon Road neighborhood—because it was cheap, if you can imagine—were determined to create an art for the people, and that is exactly what they proceeded to do.

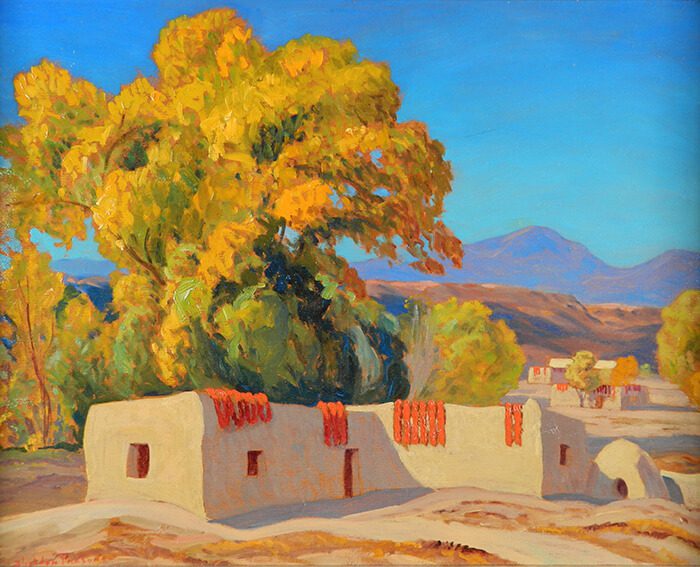

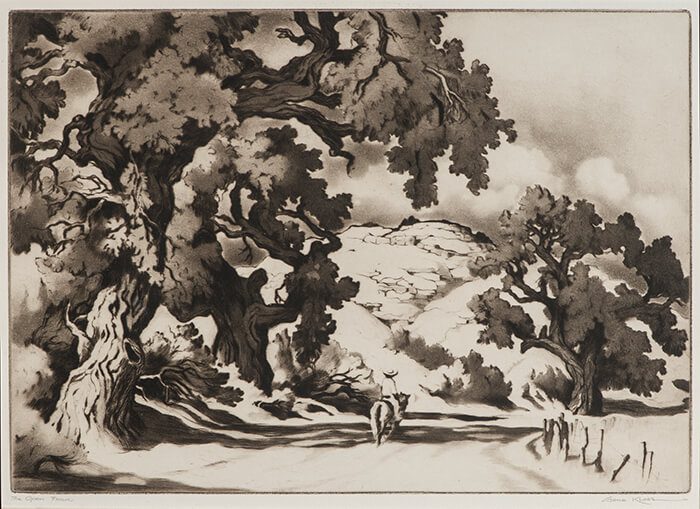

One need only take a look at a small oil-on-panel piece by former New Yorker Sheldon Parsons in order to understand how successful the early Modernists were in presenting, as matter-of-factly as any Ashcan painter did in the slums of Manhattan, quotidian life in northern New Mexico. In Alcalde NM, a simple low-slung adobe complex with red-chile ristras drying on the walls is set against a cottonwood, its leaves aglow in brilliant oranges and yellows. Above this radiance, the deep blue of the sky seems overwrought, though any local can tell you it’s the real thing. Parsons’s colors are ridiculous, deeply saturated, and true to life; the Ashcan’s dark, sooty palette had no relevance in New Mexico. Alcalde is a very simple landscape, as is his September 30, a picture that refrains from indulging in sentimentality. In fact, it is brushed with such a light hand that it is nearly an oil sketch, a thing of color and line with a matte finish that belies the rosy gold hues of autumn here. Exhibitions such as this one need to be seen through the eyes of the avant-gardists themselves; we have ruined our vision with an abundance of contemporary knockoffs of precocious scenes based, usually poorly, on the type of work by the cadre represented in LewAllen’s gallery of regional Modernism. Bisttram’s depiction of the Ranchos de Taos church and Dasburg’s pastel vision of a Village Road have become signs of a now-hackneyed “Santa Fe style” of art. This show slaps us back to our senses; these early Modernists were on to something exceptional that should probably have come with a warning for future generations: “Do not try this at home.”

Surprisingly, the Santa Fe connection to American Modernism has roots in New York. The Armory Show in Manhattan in 1913 brought the avant-garde face to face with the Academy, only to spurn its faded charms. We know that several of the artists in Quest for the New saw the landmark Armory exhibition; a couple even participated in it—Dasburg and Sloan. The fact that Sloan and his wife spent thirty summers in Santa Fe is telling, especially when considering that Sloan shared credits with Robert Henri as a central member of New York’s Ashcan gang who appalled the Academy by painting gritty scenes of life in the tenements. It was Henri who convinced Museum of New Mexico founder and director Edgar Lee Hewett to introduce an open-door policy that included so many of these young Modernists in the new state capital’s arts center.

In a conversation, curator Newman expressed wonder at the intimate relationship between Manhattan’s bohemian set and the renegades of Santa Fe. Of course, romanticizing the spirituality of New Mexico has become a tired trope. Nonetheless, it is out of the cliché that truth emerges. It was an undeniable sense of the power of the place itself that lent an overwhelming authority to a Modern art that would ultimately be distinguished as American, rather than European.