Esther Hz discusses soil and soul in her studio and reveals her passion for farming through zoetropes created for the exhibition agriCULTURE at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

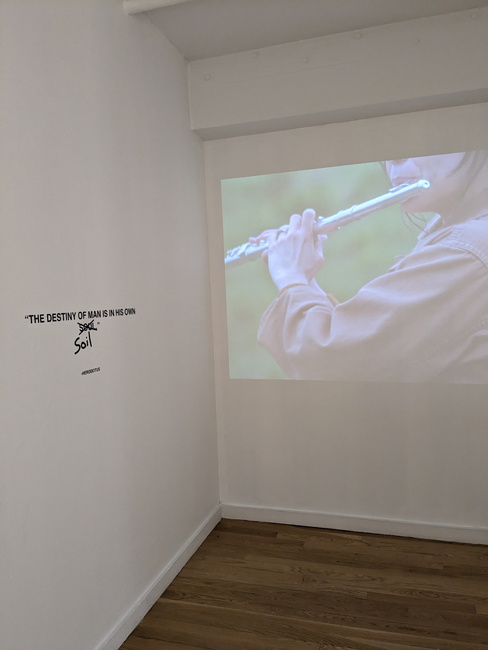

Esther Hz recently played her flute at 262 hertz to a group of cows on a vegan, biodynamic farm. (As the symbol for “hertz,” a unit of frequency that measures, for example, the sound of a flute, Hz offers “hertz” as one possible pronunciation of her name, which is short for Hernandez.) At first, the cows ignored her, but soon they got into the groove, exhibiting conscious awareness of her and their surroundings.

A recording of this performance is included in the multi-venue group exhibition agriCULTURE: Art Inspired by the Land. While the Denver-based curator and artist alludes to scientific studies about the benefit of music to de-stress cows, Hz finds the experience mostly de-stressing for herself.

“I started to get obsessed with cows [including] cows on social media [portrayed as] psychic creatures,” Hz comments before relating a recent TikTok video in which a herd of cows leads the police to a car thief who attempted to hide among the cows after crashing into their pasture.

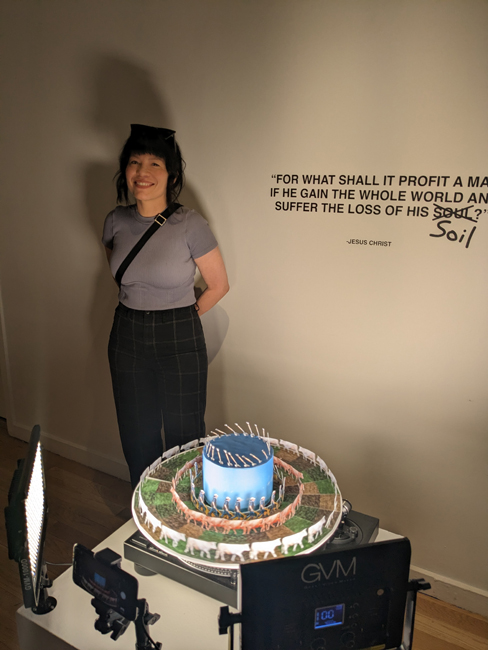

While we were both diverted by the soulful soil she praises in her zoetropes for agriCULTURE at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, Hz’s artistic and curatorial practices demonstrate a commendable breadth, spanning interests in the natural world, the human psyche, and cosmos beyond. As head curator of the downtown gallery Union Hall, she curated Traverse, an exhibition of performance and video works for Denver Month of Video, which overlaps with her interest in land and art. The artists featured in this show interact with various landscapes—from Chrissy Espinoza’s haunted and claustrophobic motel interiors to Jenna Maurice’s whimsical performances in the expansive desert-scapes of California’s Death Valley—sparking discussions of how one’s self relates to and interacts with one’s environment.

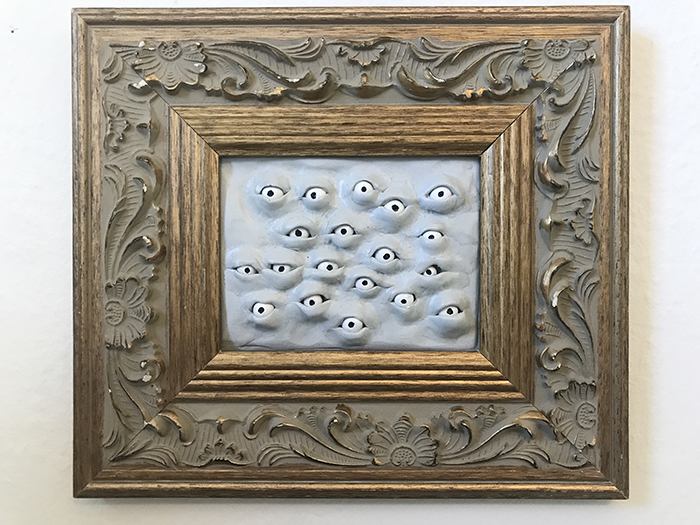

As a self-taught artist, Hz experiments with various media, including body casting, puppet-making, and automaton construction. Moreover, Hz seeks healing through her art practice as she finds creative and lighthearted ways to confront personal or collective psychic injuries or stresses.

“I’ve been told [that] all of my work is so different,” Hz half-laments from her studio in her apartment in the City Park neighborhood. Having recently moved her studio into her home, it looked more like a home office, neatly littered with artistic experiments made from plaster, clay, and apoxie sculpt. Following an interest in stop-motion film, Hz plans for her cartoony sculptures to animate themselves through internal mechanisms. Such upcoming pieces include moving, molded body parts hanging inside box frames.

Hz has always considered herself a practicing artist, but, as a former farmer, she found little time for art-making. Additionally, having attended a permaculture school in Eugene, Oregon, before urban farming at Produce Denver and then managing the urban Blue Bear Farm at the Colorado Convention Center, Hz remains passionate about agricultural work as an act of self and communal service—providing self-sufficiency and the opportunity to deeply nourish the masses. And, as Hz informed me, it all starts with good soil, the micro-biomes that line our digestive tracts, betraying where we source our food (which, under capitalism, is not necessarily where we live).

Soil plays a crucial role in Hz’s work for the agriCULTURE exhibition, which paired artists with Boulder County farmers. Connecting with Aspen Moon Farm in Longmont, Colorado, Hz worked with a biodynamic farm following the cosmic philosophies of Waldorf school founder Rudolf Steiner. Emphasizing the sacredness of soil, biodynamics uses natural and mystical techniques to enrich crops. Thus, the ten unmilked and unbutchered cattle they keep produce fertilizing manure—and that’s it. These bovines also enjoy the occasional schoolchildren choir (if not Hz’s flute).

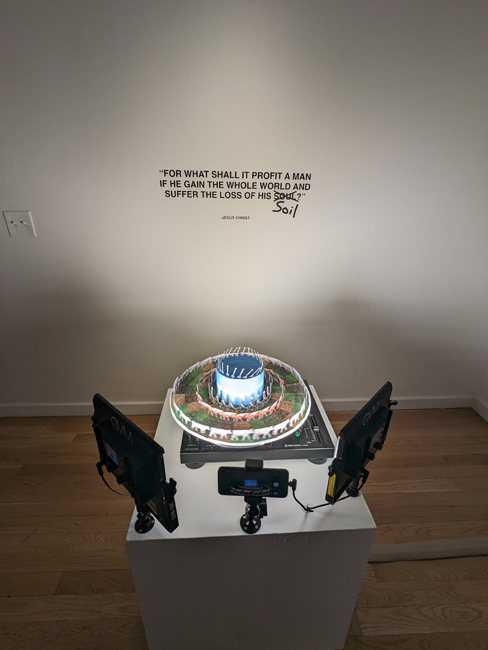

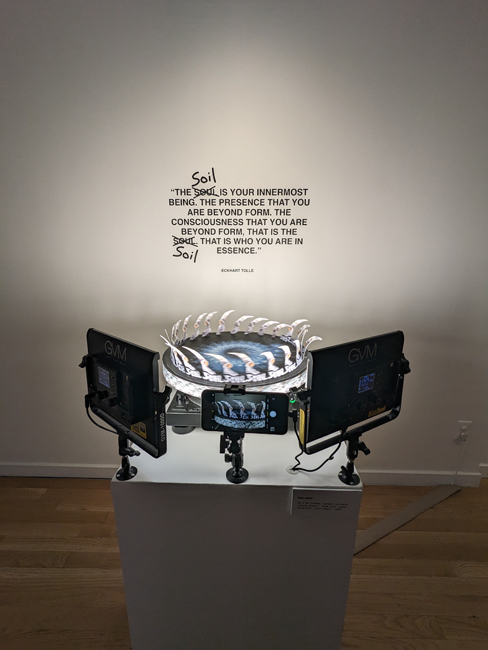

Taking the metaphysical implications of Stenier’s biodynamics to heart, Hz’s two zoetropes for agriCULTURE consider the soil’s mystical wheel-of-life significance. Enabling life through nutrition, soil also disables life through food scarcity when mistreated by chemicals and other nutrient-stripping disruptions.

Hz’s Celestial Beings honors the soil-keeping cows while Soil/Soul animates a particular Steiner-inspired method of soil enrichment known as BD500 “cow horn manure.” Demonstrating the ritualistic production of BD500, in which the farmers of Aspen Moon bury a manure-filled cow horn, this zoetrope contemplates Steiner’s pseudoscientific hypothesis that the horn “radit[es] astrality,” assisting digestion and, thereby, composting. Linking the soil’s micro and macro aspects by depicting the cosmos above and micro-activity in the ground below, Soil/Soul reminds us that as earth cultivates life, it also reclaims it in death, returning the decomposed matter to the universe.

Tones of spirituality, comedy, and healing emerge as powerfully legible focuses in Hz’s oeuvre. Occasionally working in the nonprofit sector, including with girls and women from the foster care system, Hz has invited others to play with her in her studio, listening to their histories and visually replicating their stories into art pieces that might offer pathways to self-repair.

In her 2018 sculpture Genesis, Hz cast a young woman’s face in plaster, creating a visage in which oyster mushroom mycelium overtakes half of the head cast. Hz met this person, dealing with dying and deceased parents and substance abuse, through her nonprofit work. Both Hz and this woman agreed that a mushroom mask justly represented her experiences.

Returning to her fascination with dirt, Hz expounded on bioremediation—the natural detoxification of soil—as a metaphor for “de-cluttering” or cleansing our psyches and thereby accessing our “truer selves.” Genesis thereby experimented with mycelium to symbolically and psychically palliate her grieving collaborator.

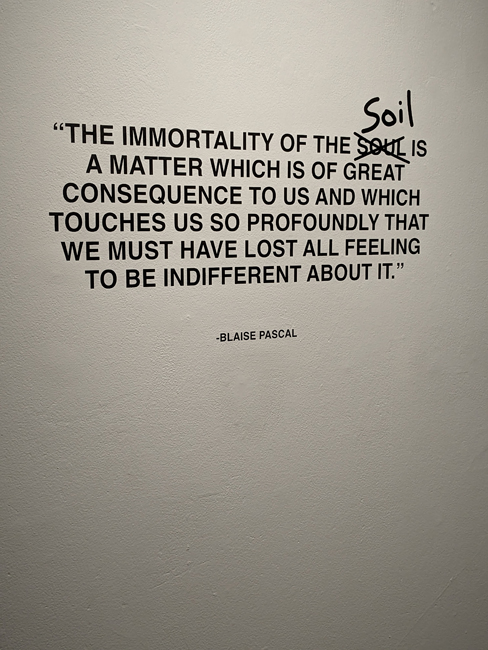

In a predominantly irreligious art milieu, searching for an authentic self becomes a tandem inquisitiveness about the soul. At the opening of agriCULTURE, Hz printed quotations about the soul, replacing “soul” with “soil.” Quoting Herodotus, for instance, Hz offers: “The destiny of man is in his own soul soil.” This rephrasing reminds us of our rootedness in the land we occupy, how inextricable physical existence is from that of the mind or spirit, and how our treatment of our surroundings profoundly impacts our future. Such metonymical slippage also underlines Hz’s distinctive artistic voice, using humor to accentuate her intellectual acuity while bolstering her audience’s awareness of the magical elements of everyday existence.