SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe

October 7, 2017 – January 10, 2018

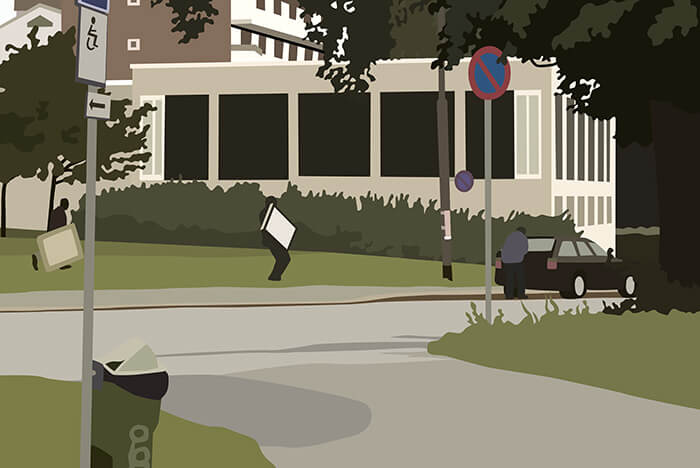

Few artists have explored flatness as deeply as Kota Ezawa. Using digital tools, for the past several years Ezawa has transformed appropriated imagery into deceptively simple compositions. A Rembrandt loses its impasto and atmospheric perspective to become a series of organically shaped tiles of color, or a Shang dynasty vase becomes a two-dimensional silhouette. Many of these digital drawings Ezawa then transfers to the surface of lightboxes, so the resultant objects glow with an almost eerie luminosity. His current exhibition at SITE Santa Fe’s newly expanded SITELab revolves ostensibly around the idea of crime and theft. The Crime of Art, like Ezawa’s works, is also a deceptively simple title. Almost all of the works address art theft in some way: lightboxes arranged salon-style display Ezawa’s renderings of all the missing items from the famous 1990 heist of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Also present are images of the museum as it exists now; Gardner insisted that her prescribed installation be permanent, thereby prohibiting the replacement of the paintings. So the frames stand, empty and seemingly awaiting the return of their charges. Other lightboxes picture scenes lifted from surveillance footage of the 1994 theft of Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

The monograph published in conjunction with The Crime of Art includes works not in the Santa Fe installation—a rendering of The Scream, an image of the famous telecast of the O.J. Simpson verdict, and others. The book’s essays offer a glimpse into some of Ezawa’s intentions and the effects of his paintings in a broader artistic context. All three writers note the artist’s pared-down style, which hearkens back to paint-by-numbers and collage. The significance of Ezawa’s style is most striking and compelling when used in the works that reproduce paintings. Considering differences between original and copy leads easily into discussions of authenticity and aura, a favorite topic of art historians and critics. But what of the images that picture not the works themselves but robberies in progress or their aftermaths in the museum? These lightbox works don’t lend themselves to the same interpretation as the replicated paintings. It might be more productive or interesting to discuss them in relationship to digital surveillance technology, or as the presentation of the action of theft as an artwork itself. But these interpretations don’t really go anywhere. Ezawa’s ubiquitous style flattens his works into a cohesive visual whole, but it also belies a conceptual fluency that doesn’t extend to his varied subject matter. He has unified the works together under the rubric of theft, but in the process the individual works don’t necessarily hold up on their own beyond their recognizability.

And perhaps this is Ezawa’s endgame. His works don’t illuminate the motivations behind crime so much as test the limits of recognition. How abstracted can his works become before we lose sight of their referents? In a 2008 interview, Ezawa alludes to this notion: “I’m trying to look at my own work with cold eyes—not liking or disliking it—just trying to see what’s happening. And I have a feeling that the imagery that is my animation is hyper-recognizable, in a way more recognizable than the original.” Here Ezawa seems to be saying that his work is more recognizable as his own than the original is recognizable on its own; his style has become more identifiable than his source material. Ezawa is specifically referring to his digital animations, which splice together fragments from films. In The Crime of Art, his video of the same title features sequences portraying art theft from Hollywood movies—among them How to Steal a Million (1966) and The Thomas Crown Affair (1999)—refigured in his signature style. If a viewer weren’t familiar with the films, the references would not necessarily matter for an understanding of the action on screen. But the understanding that comes with such comprehension is easy and fast, not necessarily signifying more than the idea of theft. The ideas embedded in the films themselves, of movie stars as thieves, of Hollywood’s tendency to glamorize a heist by laying a soundtrack and creating suspense through editing and plot, are lost in Ezawa’s reworking of the imagery. Not that such interpretations are impossible and that recognizing an abstracted version of the original isn’t fun—the man standing behind me in the gallery while I watched the film exclaimed, “That’s Peter O’Toole!” when he recognized the scene from How to Steal a Million, even though the nondescript face on the screen looked nothing like O’Toole. This seems to be part of Ezawa’s intention: to pluck images of popular culture or of high repute out of their historical specificity and to level them all with his stylistic technique. Many degrees removed, the flattened images can’t help but function in a new way, as sites of remembrance and recognition.