Psychoanalytic wordplay about aliens, isolation, space, and place.

Stay-at-home and quarantine orders are the most recent and blatant expression of contemporary neoliberal society’s shift toward an anxious, disconnected social isolationism, a so-called immunodemocracy1 whose sovereignty is predicated on keeping the “infected” Other outside its borders—consider the opposition of immunity to community. Humans, as social animals, are naturally affected by and push back against this imposed isolation by, for instance, seeking out or longing for shared places in which to connect with fellow humans. As art critic and activist Lucy Lippard puts it, place is “the geographical component of the psychological need to belong somewhere, one antidote to a prevailing alienation.”2

And while, yes, the desire to belong somewhere, is one response to an increased isolationism, we may feel the opposing desire to embrace the alienation, and to be elsewhere from others. Think back to the early days of the pandemic when perhaps you felt a sense of relief from being physically isolated from the workplace.

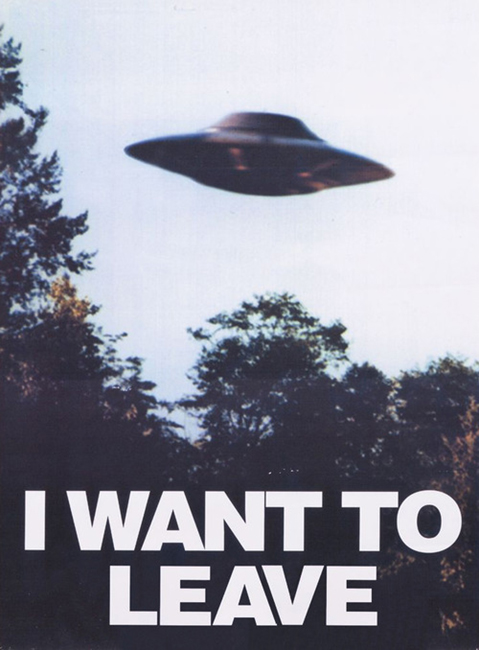

There’s a meme floating around the Internet that sums up this isolationist drive fairly succinctly: it’s the UFO image from The X-Files’s special agent Fox Mulder’s “I Want to Believe” poster, but instead it says “I Want to Leave.” This meme embraces alienation, not only through its direct reference to literal aliens, but also the sentiment of leaving here, this somewhere, to go elsewhere. The Germans have the word Fernweh to describe this phenomenon3; we have this X-Files meme. Think perhaps about responding to the anxious isolation one might feel from being at a crowded party, by leaving, isolating further, alienating oneself—this is self-care.

Or perhaps one might take this to its extreme, like Richard Branson or Elon Musk, and seek to literally leave the planet into that great expansive elsewhere of outer space, or the dead planet Mars. There is a clear death drive in this extreme, rocketing into the cold nothing, toward the dissolution of self, contributing more carbonic waste in the form of spent jet fuel to the atmosphere of a supposedly dying planet left behind. This is the necropolitics of deciding who does and does not survive the death of this planet.

But we’re mostly not stargazing billionaires, and our death drives aren’t generally quite so apocalyptic. In fact, there’s a little death drive in every life-affirming drive, and vice versa—as psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan points out, “the distinction between the life drive and the death drive is true in as much as it manifests two aspects of the [same] drive.”4 Following this logic, we can view the drive to belong somewhere (life drive) and the drive to be elsewhere (death drive) as not oppositional, but pointing in the same direction, away from the anxiety induced by neoliberal ideology.

Whereas belonging creates a strong networked fabric of resistance, isolation can provide the distance needed for new perspectives to develop. The gravitational pull of elsewhere may be strong enough to pull one out of the bubble of immunological society into an outer space which is not just Other, but alien. That is, while it can be difficult, isolation can be life-affirming by introducing one into a weird elsewhere where a counterculture is bound to incubate. Just because I want to leave, that doesn’t mean I don’t also want to return—hopefully with spectacular, incomprehensible, alien ideas and ways of living.