Desert X 2021 offers large-scale, photogenic works that, while politically charged, lack a distinct impact.

Desert X 2021

March 12–May 16, 2021

Coachella Valley, CA

Awe, as defined by neuropsychologist Paul Pearsall, is the “overwhelming and bewildering sense of connection with a startling universe that is usually far beyond the narrow band of our consciousness.” I did not experience Awe at Desert X.

Desert X is a relatively new outdoor international art biennial (now in its third iteration in California) whose installations are spread out at various locations across Coachella Valley. The exhibitions have featured big-name, international artists (Doug Aitken, Mary Kelly, Postcommodity, Jeffrey Gibson, Alicja Kwade to name a few) and curators along with artistic director Neville Wakefield.

Previous DX biennials seemed to have fallen into the category of Big Fun Art (Desert X is not mentioned in the linked 2017 article, but launched in the same year), with largescale, superbly photogenic works that looked striking on Instagram punctuating the desert landscape with decidedly un-desert-like features: bright colors, crisp edges, lights, and reflective surfaces. Desert X 21, however, falls only into the Big category, forsaking the Fun for a more political perspective. This is perhaps their corrective and response to the roundly criticized Saudia Arabia edition held in 2020, which was sponsored by the Saudi Arabian government, a body long known for its human rights violations.

DX 21 still brings the Big, but many of the works are more politically charged, and more desert-driven than aesthetically driven, but many failed to make much of an impact despite this welcome shift in curatorial direction.

The Fun is still to be had, however, by spending the better part of two days driving around Palm Springs and Palm Desert with some friends: through sparkling downtown, gritty residential neighborhoods, through incredible wind farms, and up steep hillsides with expansive views of the human-covered, hostile desert landscape (sensible footwear recommended) to view each of the works.

According to Desert X’s didactic materials (a program guide and map that can be picked up at the très cool mid-century modern Ace Hotel), DX 21 was curated along the premise of the desert as a concept, place, and dramatic intersection between the natural world and the human world. Of the eight installations that were open during my visit, few really met these criteria. The strongest take on these ideas was Never Forget, by Nicholas Galanin, a Tlingit and Unangax̂ artist. Constructed as a mirror of the Hollywood sign, the words “Indian Land” occupy a sweeping valley adjacent to the Palm Springs visitor center, echoing the Hollywood sign’s bombastic promotion of residential development. Sitting on the edge between Palm Springs’s distinctly Californian flavor of pristine facades and the rocky desert mountains, Galanin’s monumental installation recalibrated the advertising language of signage as a rejection and reclamation, one that has reverberated even more as it continues to be shared across social media.

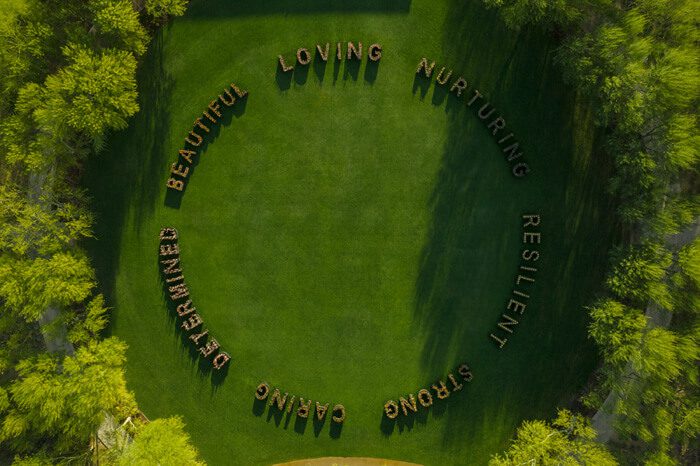

Within the circular tondo of the Sunnylands Center and Gardens, a beautiful desert garden, was the most lovely and most frustrating installation. Ghada Amer’s Women’s Qualities consisted of raised, letter-shaped garden beds that spelled out words such as “Beautiful” and “Resilient.” These cliched qualities of women were so baffling that I turned to the program guide to demand an explanation. The text claims “Recognizing that women are taught to model behaviors and traits shaped by others, and that art history—the history of painting, in particular—is largely shaped by expressions of masculinity, Amer subverts these frameworks through aesthetics and content.” No such subversion occurred for me, nor for the families enjoying the paradisiacal gardens, pointing out, “See? Isn’t mommy beautiful?” to their children. (But you know what? She is.)

Zahrah Alghamdi’s What Lies Behind the Walls was particularly memorable. A freestanding monumental wall made, from the distance, of slabs of dense earth (up close, of foam flocked with dirt). It served no purpose as a wall, and thus spoke to borders, to the arbitrariness of human politics, and to our smallness and hubris on this miraculous rock spinning through space.

If you really want to witness a dramatic intersection between humans and nature, however, drive sixty miles south to Bombay Beach. This small enclave sits on the edge of the Salton Sea, a large lake made by accident in an attempt to create and irrigate farmland in the desert.

After the valley filled with water, enterprising types seized on the opportunity to create a lakeside resort in the 1950s, which crumbled when the lake became toxic due to chemical runoff from the farms beginning in the 1980s. What’s left is a small neighborhood and the ruins of the resort on an otherwise forsaken beach. Here, a smattering of ironic-verging-on-nihilistic art installations dot the beach. These include a “dead sea forest” (literal in every way), a solitary swing set out of reach in the water, a forlorn mailbox, and an upholstered chair where you can sit on the precipice and contemplate falling out of reality altogether.

In the village, it’s sometimes difficult to discern occupied dwellings from art installations, from what’s simply been abandoned to graffiti. A Bombay Beach Biennale instigates the creation of new works, some of which are seemingly left intact to linger unattended, probably to decay. There’s a drive-in movie theater consisting of scrapped cars all facing a blank screen, and an office for Sotheby’s International Reality.

There, in a remote, dead-fish-smelling scrap of desert, I was more aware of the absurdity of humanity’s tenuous relationship with the land and desert, felt its fallout more viscerally, and witnessed the curious, charming capacity of humans to turn ashes into something inspired than I did among the works of the international coterie of artists and curators of Desert X. On Bombay Beach, I was pulled out of this world for a moment. And when I came back, I could see everything around me in sharper focus, as though through a cleaner lens. That, I believe, is Awe.