Santa Fe has been at the forefront of historic preservation since the early 1900s, when it fashioned itself the “City Different” in response to the “City Beautiful” movement that was driving growth and tourism across the U.S. Since that time, architects and preservationists here have worked to protect and promote an architectural language designed to entice people to Santa Fe.

Our first century of preservation was not without issue, however. The vision of “who we are” was defined by a particular group of people who critics say had romanticized ideas of what that meant. It turns out, the detractors are not wrong—the Santa Fe Style, formalized in 1957, is an idealistic mash-up of styles pulled from a selective memory that favored “traditions” that did not really exist in Santa Fe until they were introduced in the twentieth century—including layered massing, upper floor terracing, and facades borrowed from Acoma and other Pueblos and their missions. The critics are also not wrong that the architecture that was mandated does not respond to our culture or environment in the sustainable ways that our early vernacular design—based on local needs, materials, and traditions—once did.

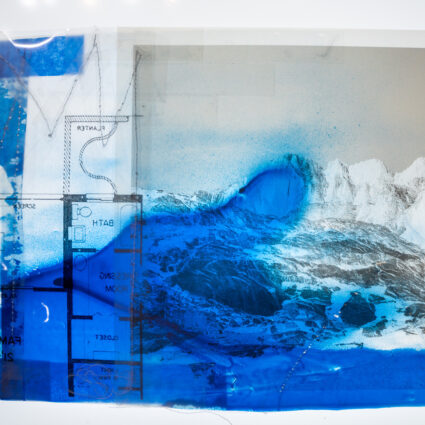

This discussion of what is authentic is important, as throughout New Mexico—despite our efforts at preservation—the buildings, sites, trails, and lifeways that once provided for the people have often been obliterated. We borrowed shapes and materials, rather than harnessing our historic practices—especially our water, building, and agricultural traditions. This is the problem with emphasizing “style”: it is fundamentally a surface treatment.

We are also confronting a generational difference in the community as many of our older preservationists are retiring. Preservation was a local movement before it became a profession, and while the older generation may have grown up in the neighborhoods they are trying to preserve, the economy has shifted such that younger generations of preservationists are more likely to have moved around, and will likely never be able to afford to live in (and thus take ownership of) the places people want protected—especially not in Santa Fe.

Plus, bodies—and banks—break. The cost and the hard work of regular maintenance for traditional adobe is prohibitive over time, which is why we don’t build much of it anymore. Even our local preservation institutions—some nearly a century old—have struggled. One quietly sold off most of its inventory of historic homes in recent years; others are attempting to offer guidance in areas with very different functions and demographics than in previous decades. Still other institutions have few options other than to throw their efforts behind the preservation of public buildings, because those projects are some of the few able to capture grant funding. Preservationists working over the past few decades have likely witnessed at least one project that took a decade or more to raise the money for—and dozens of projects fail to launch, usually, again, due to money.

Due to the lack of housing assistance and rising prices in the high-end residential market, some of our treasured historic sites are at risk of being sold or demolished. One thing that that could help: owners of registered historic buildings—of which there are five thousand or so in New Mexico—can take advantage of an existing 25% state tax credit (it’s 50% in any arts and culture district!) applied to their future state tax liability. So spend one hundred thousand dollars on restoration, get up to twenty-five thousand back in credit. The challenge is that the credit currently has to be used in five years, meaning that it only works if you pay more than five thousand dollars a year in state taxes. This makes it so that only the wealthy and large (often out-of-state) corporations can use the program. If the legislature extended the credit payback to match the federal one—which is spread across nineteen years—it would be more feasible for individuals and small businesses to preserve their important historic places and invest that money back into their communities. This would help keep historic buildings in New Mexicans’ hands for years to come. (An aside: preservationists, including myself, are currently working with local and state organizations on a bill to expand the credit period for the 2021 legislative session, so let your state legislators know if you support this idea!)

The issue of cost should matter to all of us, because whether it’s the million-dollar restoration of the Santa Fe Depot or the many millions it is estimated to cost to restore the Palace of the Governors, tax-payers end up footing the bill for the preservation of our shared public spaces. Yet current design practice largely obscures the process and costs of restoration from the community. On one hand, I believe the public—who owns these buildings—has a right to be informed, because these restorations will only last a couple of decades and then the process will be repeated, likely for even more money. My gut check says: “Is that sustainable? Who decides? Isn’t an informed community better able to preserve?” On the other hand, I love the idea of our modern buildings representing who we are now, or who we might be—just like when they updated the Palace of the Governors to match the new ideals of Santa Fe Style in the early twentieth century and, more recently, with modern buildings like SITE Santa Fe, which would never have been realized if consensus was required.

Current design practice largely obscures the process and costs of restoration from the community.

We can see many of these current preservation issues playing out in the new Vladem Contemporary in the Railyard district. The State had a vision for a contemporary museum that utilized the footprint of a historic building that had multiple levels (thus, was not accessible for individuals of all physical abilities), so it was functionally unusable as public space. Due to that and deferred maintenance, the original space could not accommodate the museum without great expense. The State decided to hire a young, innovative architect who designed something modern that would also solve these accessibility issues. The community—different people with a diversity of agendas and concerns—was not asked to participate along the way, and many took issue with the project as first designed. One architect friend worried during the redesign (which at last took into account the community’s opinions) that these changes might result in something “designed by committee, lacking a cohesive set of goals.” As well-intentioned as the implied civic promise of “Trust us: we are hiring the best experts” is, the community gets to decide where it places its trust. And redesigning costs a lot of money. Figuring out how to balance all these voices is a complicated but necessary element of how we preserve going forward.

The Vladem museum’s use of a historic building as a base layer also highlights the need to address accessibility. Throughout New Mexico, the tradition of making one-room additions has left us with steps at many doorways and in hallways—a designer’s nightmare, as a single step almost guarantees that people will fall. Multiple steps further complicate the design due to how long corresponding ramps must be. When these elevation changes cannot be smoothed out, a building is usually relegated to residential use, even if it is quite large. As someone who is going blind and also has a broken hip awaiting surgery, I benefit from accessibility accommodations like ramps and elevators. However, as a designer, I also wonder how we can empower people to preserve great historic buildings despite these challenges. Which brings up a big question for me: if an old building is not “great,” is too big for a home, and cannot be made accessible, shouldn’t we (clutches pearls)… consider other options?

Ultimately, people are the most important consideration in preservation.

When I speak to my peers about these issues, we always circle back to the idea that our community and what we preserve has to work for everyone—not just be pretty. For me, the resolution comes down to two key points: 1) Without innovation, we cannot get to sustainability, because we cannot afford what we have been doing, and we cannot afford not to change. And 2) The “best intentions” have actually made invisible some great old buildings and their incredible histories. We should work to protect these, like Olive Rush’s house on Canyon Road, the Fényes-Curtin-Paloheimo house on Acequia Madre, and the Spanish Pueblo Revival El Delirio at the School for Advanced Research. So I say let modern buildings be new and respectful and real! Because in fifty years, to the kids growing up here now, these buildings might just be their generation’s historic treasures.

Ultimately, people are the most important consideration in preservation. It is vital not only to give them a voice and access, but also to make sure that the talented staff in our city and state governments are allowed (even encouraged) to work towards preservation for the long term and good of all. Right now, these offices meet their mandates and “get by,” but positive change requires investment in the future. If we ask our mayors and our legislators to provide additional funding, these offices could work to increase brick-and-mortar grant funding, improve policies and programs, streamline processes, and create and administer grant programs—all of which would offer a lifeline for more New Mexicans to preserve the places we love.

The preservation issues we face are bigger than one article can address. This is just the start of the conversation. In coming issues, as well as in salons and panels, architectural and community leaders who care deeply about this place will join us to discuss how Santa Fe and New Mexico can exercise sustainable preservation leadership for the next century.

Let’s fix this.