Name: Virginia Dwan

Born: October 19, 1931, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Lives: Santa Fe, New Mexico

Role: Gallerist, art patron, and social activist

Quote: “I generally say they had to exist—they had to be built. That is still my feeling. These were pieces that demanded to be built, because they were significant additions to humanity.”

Virginia Dwan, best known in the Southwest for her support of land art and artists, as well as the Dwan Light Sanctuary in Montezuma, New Mexico, boasts a career that reaches far beyond the desert. Originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota, Dwan got her start in Los Angeles with the Virginia Dwan Gallery, which eventually expanded to New York, where she represented artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Yves Klein, Sol LeWitt, Edward Kienholz, and many, many more. Dwan, the heiress of manufacturing conglomerate 3M, was able to take risks on challenging art. She played a major role in supporting some of the most definitive earthworks, such as Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson, The Lightning Fields by Walter De Maria, Double Negative by Michael Heizer, and the still-in-progress Star Axis by Charles Ross. She is still a passionate supporter of the arts and speaks fondly of working with artists and being a part of the creative process.

Dwan moved to Santa Fe more than thirty years ago based on a recommendation from her friend and notable land artist, Nancy Holt. “Nancy said it was a beautiful place with amazing sunsets, which to me sounded like technicolor. When I finally visited for the first time, it felt like coming home. New Mexico spoke to me, and it was very powerful. I have been here ever since.”

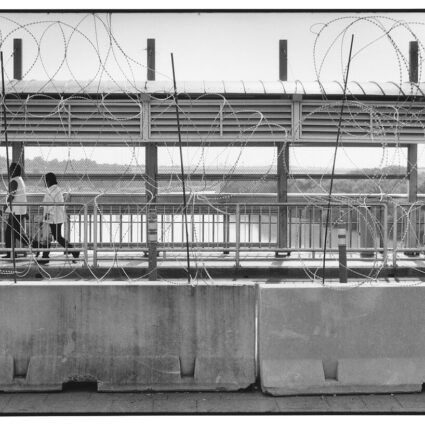

Virginia and I scheduled a phone interview on a Sunday. That particular Sunday fell only hours after two deadly shootings—one in El Paso, Texas, and the other in Dayton, Ohio. We kept our date, but the mood was heavy as the conversation kept drifting towards the news. Dwan, eighty-seven years old, said that she had been thinking about the shootings for much of the day. “It seems particularly clear to me today that diversity is something that people fear and are challenged by. Both tragedies were based on not wanting strangers to come in. Not wanting a different perspective. Not wanting a different language, because that’s uncomfortable. People are the same way about art. They want a nice landscape that they can feel comfortable about. They don’t want to see the different or difficult perspectives.”

She has been compared to the Medici family, who spurred on the art of the Renaissance, her involvement with minimalism and land art having made a profound impact not only on the careers of individual artists but on all of art history.

“The art that I showed in Los Angeles and New York was considered avant-garde in the 1960s, but what it really amounted to was artists seeing through a different lens than most of us do most of the time.” The “different lens” Dwan speaks of was something seemingly effortless for her to tap into, where others—even major players in the art world—could not. Where there was a wash of color or a mound of rocks, she saw something more.

She went on to speak about land art and offered a surprising perspective: “Even land art brings to mind that we are preparing to go live on Mars. There is an assumption that the earth will not be inhabitable in the near future. That really, really engages me. I have great-grandchildren, and the thought that the earth will change and be trashed is quite painful to me.” The Dwan Light Sanctuary in Montezuma is a response to these concerns and aims to offer an antidote. The sanctuary is a non-denominational gathering space that is rooted in faith and something “deeper than function.”

Dwan sees art as an active force that can shift perspective and has the power to ignite change, even if only on an individual level. The artworks she supported have challenged the state of affairs; many are still not even accepted as art by some. Dwan continues to believe deeply in the artworks she has supported and feels that the pieces “demanded to be built, because they were significant additions to humanity.” She was one of the few gallerists and art patrons to encourage and help produce such demanding and difficult work, thus paving the road to new movements. She has been compared to the Medici family, who spurred on the art of the Renaissance, her involvement with minimalism and land art having made a profound impact not only on the careers of individual artists but on all of art history.

We spoke of many difficult things that day—from climate change to mass violence. She kept reiterating, “I want to do something.” For someone who has already done so much, there is still much to do. Her hopes are that land art will continue to draw attention to the planet and act as a catalyst to change perspectives, slowly, person by person.