A voice calls to me from a car parked on Washington, just off Silver, and I bend to face the woman in the driver’s seat.

“Are you looking for something in particular?” she asks.

“Yes, that mural,” I say, pointing to the painting that stretches across the wall of Kei & Molly’s Textiles, behind her. “Why? Do I look lost?”

“Sometimes,” the woman—a stranger—startles me by saying.

A week earlier, at the start of a self-styled tour of Albuquerque murals and street art that will include more than fifty pieces, I’m standing on Broadway, lost in the Albuquerque of Francis Rivera’s Desert Bloom. I struggle to orient myself at first even though Rivera’s perspective of the city, looking north from the Guadalupe overpass, is mere blocks from my own vantage point at the South Broadway Cultural Center where the mural hangs. Its broad scope speaks to the influence of the Mexican muralists, but there’s no semblance of strife, historic or present. It is a vibrant, jazzy piece, nostalgic for a version of the city that is unfamiliar to me. Or is it, I wonder, crossing to the murals at Castillo Park, the city itself that has become unfamiliar after many years lived away?

I climb back on my bicycle and make my way north. For the moment, I am one part native, two parts transplant, riding through my hometown as I would through another country, eyes open for what I haven’t seen, thinking about what it means—what it takes—to know a city.

For the moment, I am one part native, two parts transplant, riding through my hometown as I would through another country, eyes open for what I haven’t seen, thinking about what it means—what it takes—to know a city.

Over the bridge, near the railyards, I find Crossroads Conversations, “a mural for the community, by the community.” Against a magenta/black sky, three human silhouettes filled with icons of identity and place ride a blue line that might be the river or might be the edge of day. One sits astride a lowrider bike whose front wheel encompasses a scene with four Latina women sitting on the roof of an early 1950s coupe. In her torso, near her heart, stands a kind-eyed, mustached man in a cowboy hat, his right hand closed around a tool for working the land. Hibiscus blooms float from her hands to her hair. Another figure pedals a bicycle whose seat is a for sale sign.

A couple blocks over, I stop at the former B. Ruppe Drugs—one of the landmarks in Rivera’s mural at the SBCC—and admire Nani Chacon’s graceful portrait of the late Maclovia Zamora, an herbal healer who was co-owner of the pharmacy. The few scraggly weeds pushing up at the base of the wall seem to belong to the mural, with its oversized renderings of yarrow and other plants Zamora used as a healer—work not inconsistent, in her cultural tradition, with her Catholicism.

The murals in Barelas feel rooted. They are on cafés, churches, the walls of old storefronts. I cycle through the neighborhood often and always feel my heart smile when I pass Working Classroom, in what used to be La Mexicana Tortilla Company, but today is the first time I stop to fully take in the art that covers its walls. On the west, in Educational Justice will guide us into the future we deserve (2017), a person whose skin is cast blue wears a cap imprinted with the Diné words for “Water is life.” Cloudy, painted skies threaten to storm, but leaves and buds sprout from a small book, Las Mujeres, that the person’s hands are ready to catch. This is just one part of a complex mural, led by artist Layqa Nuna Yawar and created, like most, by the hands of many.

Down Eighth, I stop at a quartet of pieces near Coal and continue to Park Avenue. On one wall off Ninth, a woman’s face, chiseled and serious, gazes over a landscape of jagged plateaus. Green lines divide the red and turquoise stripes of her face, and white lines divide the green and pink strips of terrain. This is Joseph Arnoux’s Blood Quantum. The title refers to the controversial, arbitrary terms that divide those qualified from those not to gain membership in certain tribes. As I ride on, my mind wanders to other arbitrary terms—terms used to define belonging to nations, cities, even neighborhoods.

The next stop on my tour, pulled from the handy but by no means comprehensive map at murosabq.com, is in the Sawmill district. I ride in circles—discovering another mural along the way—before realizing that what I’m looking for is behind locked gates. I could seek entry, but I’d be breaking a rule I established somewhere along my ride through Barelas: this tour will feature no murals that require payment.

Nearby, I pass a Little Free Library and decide to see whether the books inside can tell me anything about the people who live in this neighborhood, where townhouses on converted industrial sites abut older, quirky, working-class homes. Amidst the usual V. C. Andrews novels and outdated Frommer’s guides, I find one gem: a well-loved copy of Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony.

I’m looping south, again. On First, wild letters and war machines on an auto shop wall mirror heaps of metal being processed across the street. Nathan Nez’s brightly colored hummingbirds hover at Health Care for the Homeless. “Learn to write!” someone has written neatly in a downtown alleyway, over Jaque Fragua’s wall of Pueblo patterns. At the Copper Building, painted on all sides during the 2018 Mural Fest, I linger with TJ Meade and Ben Harrison’s piece, where a field of sky and blackbirds, powerlines and tiny squares, is watched over by a pensive woman.

The sun is high by the time I conclude the first leg of my tour, east of Broadway, beholding the victorious call to Honor the People—Protect Mount Taylor (no date, possibly 2014).

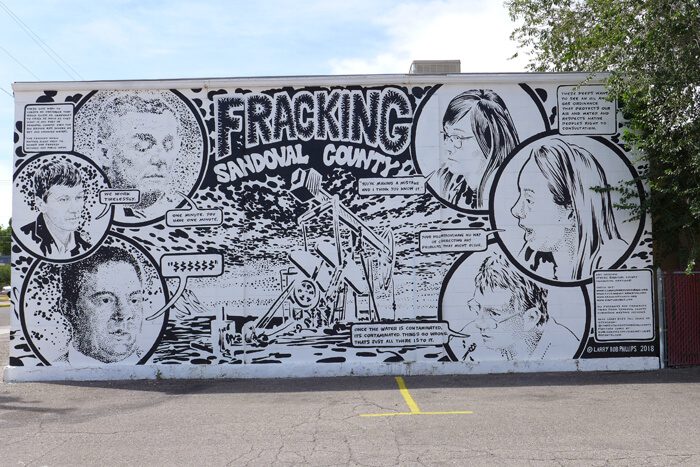

Days later, I pull into the double-muraled gas station at Lead and Yale. How many times have I driven by without seeing either mural, without looking? Facing north, a Native woman, three blades strapped to her thigh, stands across a field from an ominous horizon of pumps and drills. “Protect our water,” the work is signed—an invocation against the Dakota Access Pipeline. One of my first stops in Nob Hill is also about water: Fracking Sandoval County (2018), by the prolific Larry Bob Phillips, done in his classic monochrome, features subjects and words drawn from the actual minutes of county commission meetings.

On foot, I weave between Silver and Central, up to Washington and back, at some point acquiring a casual tour guide—a true transplant to the city, who admits to sometimes feeling lost in this country, on this continent, yet has also come to know Albuquerque. He points me to a piece by Lalo Cota, to a mashup of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

The wall behind Cowboys and Indians Antiques is an urban landscape of patterns and minimalist humanoid figures. Street art, the story goes, was born last century, in New York City; when the discussion extends beyond that, it’s often to the prehistoric caves of Lascaux, in France. But I think of Big Man Panel, created by Ancestral Puebloans in Cedar Mesa, in what is now Southwest Utah, when I reflect on the figures within figures, the otherworldliness of the people in this mural. I later learn the artist was inspired by Mimbres iconography.

Take this not as a template but as a provocation.

To write of any journey is to lie a little. I’ve omitted some of the city’s best-known murals, some of the newest, and most easily found. I’ve withheld a few personal favorites, pieces to be discovered by those who will. Take this not as a template but as a provocation.