June 14 – September 15, 2019

SITE Santa Fe, Santa Fe

I step from the gallery to a sky streaked with black, and my eye is drawn to materials: the slate-colored gravel path in the Railyard Park, the steel tracks, wood ties, the chunked granite between the rails. While I wait for the train back to Albuquerque, my attention turns to the earth, slathered with asphalt. A plump black ant hurries along with some small corpse folded into its mouth.

What Endures is, and is not, a question. It’s not incidental that I’m focused on the elemental details of my surroundings, that I want to take apart the anthropogenic landscape, break it down into its simplest ingredients. This act is central to Nina Elder’s process—and to the subjects of the featured work, which spans from 2011 to the present.

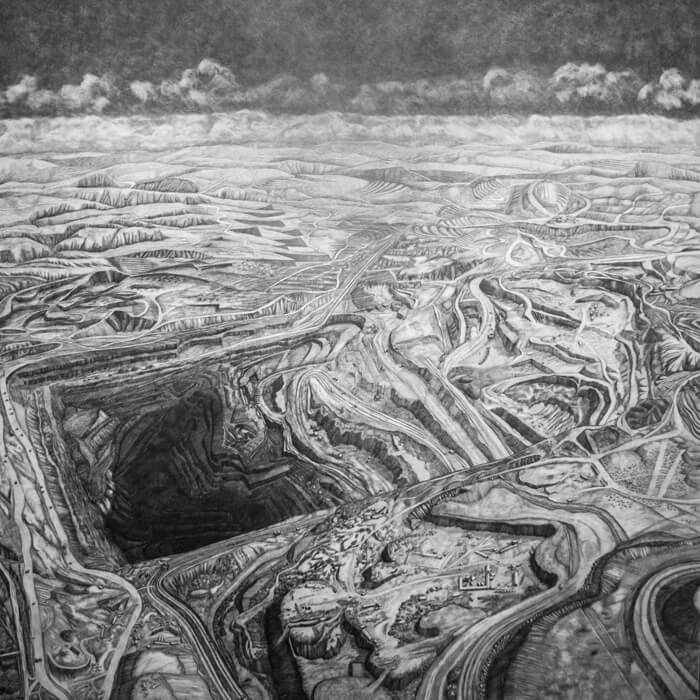

“I edit humans from these images,” Elder says in the audio guide to the show, “leaving only their enduring traces.” Several haunting large-scale drawings feature pit mines owned by the Kennecott Corporation, sites of systematic excavation, each one a unique—and uniquely ravaged—body of land. In Kennecott Corporation: Grasberg Pit, Indonesia (2016), pit benches spiral down to the vanishing center of what was once a mountain. The vast mine site descends sharply from a range of surviving peaks, and despite—or perhaps because of—the precision of Elder’s lines, it is conceptually difficult to reconcile the presence of these peaks, the tufts of cloud floating just above, with the lifeless basin at the drawing’s center.

In Kennecott Corporation: Haerwusu, China (2016), drawn with graphite and pulverized mining slag, the pit is a gaping hole, a dark point where the eye falls and falls and falls. Hills stretch off into the distance, evoking something bucolic, but pit benches and roads rut the landscape—there is no clear start or end to the excavation. Along one edge of the pit sit speck-sized squares, suggestive of cars; in the foreground, tiny rectangular structures that must be buildings. It’s here, depicting the smallness of the spaces that humans fit into, that Elder invites the familiar comparison between ants and humans.

“My ongoing questions,” Elder tells us, “are whether these are disaster sites? Or are they unintentional monuments to humanity?” In either case, they demonstrate that while we may be to the mountains what the ants are to us—miniature, yet quite consequential—a pit mine has very little in common with an anthill.

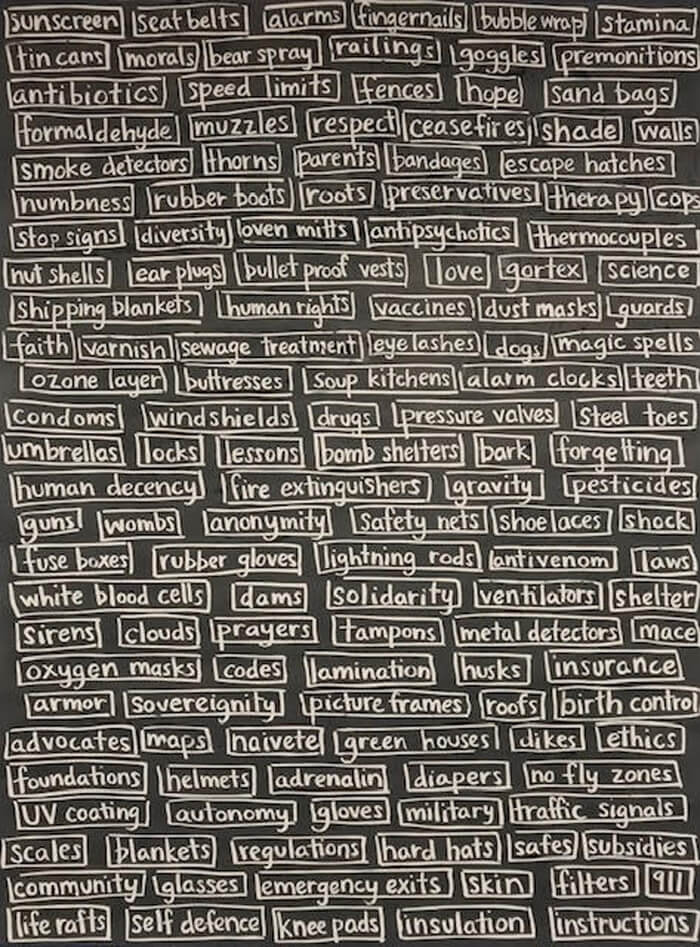

Adjacent to these drawings is work from Elder’s newest project, a series of incomplete, nonhierarchical lists. After circling through, I find myself compiling my own, inspired by the exhibition: an incomplete list of things that human society depends on. Ants are there, aerating the soil. Copper, extracted from the Kennecott Corporation’s mines, used for pipes and electronics, is there. Uranium, too.

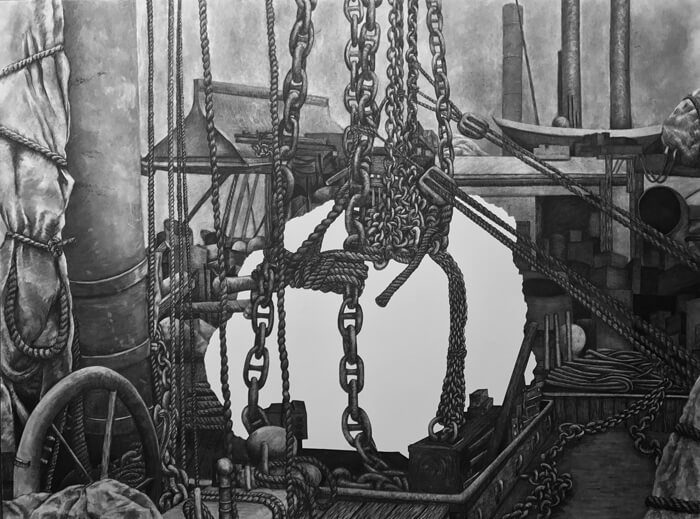

The earliest piece on display, made with graphite and radioactive charcoal, is an intricate drawing of “the gadget,” as the bomb for the test at Trinity was known to its creators. “A name diluted by the technicality,” as Joshua Wheeler writes in “Children of the Gadget,” “that it was only a test device, a name meant to hide the significance of what we were about to do. Just a gizmo or a widget. A little doohickey. . . Just toying with the nauseous joy of physics.” Elder consciously draws a parallel between her practice, getting lost in the details of drawing, and the physicists who lost themselves in the mechanical details of the bomb.

“It’s just a pile of rocks,” I say of Unprocessed Uranium (2017), somehow still capable of shock at the simple fact that uranium is a natural thing, not even a “resource,” but one of the infinite building blocks of the world, a material presence, seemingly harmless to life—just a pile of rocks until some scientists figured out that it could be used to decimate a city.

“I feel,” Elder says, “that I am memorializing wilderness lost.”