May 17 – September 22, 2019

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Often taken as a bellwether of U.S. artistic culture, the Whitney Biennial is renowned for its tendency to provoke political/aesthetic furor. This year’s controversy focuses on Whitney Board member Warren B. Kanders, whose company Safariland manufactures military equipment, including the tear gas canisters reportedly used against Mexican migrants at the U.S. border. When I stepped into the darkened screening room to watch Forensic Architecture’s video investigation of Safariland, there wasn’t a seat to be had.

But overall, the 2019 Biennial prioritizes visual pleasure over political assertiveness. Painting, sculpture, photography, video, and installation are evenly balanced; the selected artists skew mostly young (see John Yau’s analysis of their demographics and educational provenance at https://hyperallergic.com/503928/how-do-artists-get-into-the-whitney-biennial/); the scale ranges from small canvases to giant installations. Occupying one of the Whitney’s city-facing terraces, Nicole Eisenman’s impressive, if baleful, Procession features giant-sized human/animal figures fashioned with deliberate cartoon crudeness from various un-monumental materials, offering a grim satire on (the futility of?) contemporary protest marches. A few floors below, in a work choreographed by Brendan Fernandes, black-clad dancers perform their own ritual maneuvers in and around a cage-like structure, their slowly shifting postures silhouetted against the Manhattan skyline.

As I wandered its three floors, certain themes surfaced: submergence (or emergence) of one object (from) within another; visual

layering; dissection of media imagery; garbage as found object.

In the “buried within” category, Ragen Moss’s oddly shaped acrylic chrysalises, suspended by wire, are a showstopper: daubed with color and scraps of text, their partly transparent surfaces reveal other, smaller volumes nested within. Viewers drift between the two rows of gently swaying sculptures as if browsing fancy clothes in the stores at the Whitney’s heels in the utterly transformed Meatpacking District; aptly, they also bring to mind carcasses hanging on meat hooks. It’s hard to resist tapping them, wondering whether they’d yield their inner treasure if struck, like piñatas.

In Brian Belott’s Untitled series, multicolored blocks of random everyday materials are held together in ice and presented, backlit, in glass-fronted freezers—an update on the classic museum vitrine. In his Dark Silhouette series, Matthew Angelo Harrison casts ethnographic objects (spears, sculptures) within tall blocks of resin, highlighting the vexed history of anthropological spectatorship and cultural dispossession in museum culture. Cascading water and beads of moisture infiltrate the frames of Josh Kline’s photographs of canonical American buildings and corporate headquarters, implicating these authorities’ role in the climate crisis—or perhaps just pissing on them. Tomashi Jackson’s tableaux deploy layering to deliver social critique: black and white transparencies of city maps and housing form dark tassels against vibrant colors, and political campaign buttons are clustered like punctuation marks in works that explore flashpoint cases of New York urban gentrification.

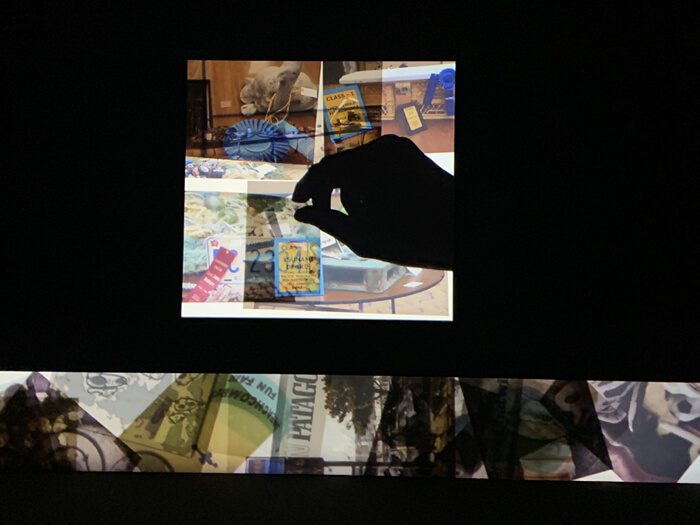

Recalling Melvin Edwards’s steel collages, Robert Bittenbender’s sculptures weave bric-à-brac scavenged from Manhattan’s streets into dense three-dimensional drawings, thick with wire and the odd plastic castoff—luscious despite their lowly origins. In another meditation on garbage, Ellie Ga’s short videos, Gyre 1-3, explore the man-made crap that gets caught in ocean gyres, washed up on shore, and competitively trawled by beachcombers. A curiously old-fashioned (again, layered) visual treatment accompanies her voiceover: a silhouetted hand periodically reaches into the main screen to select a color transparency—like picking a thirty-five-millimeter slide off a light box—then moves it to a “deck” of images on the screen’s lower margin, a magic lantern effect for the digital age.

The symbolic identity of national sports figures is scrutinized in works that deconstruct the dizzying aesthetics of television sports coverage. Jeanette Mundt performs 2-D “stop motion” by splitting her Born Athlete American canvases into vertical panels of varying widths, dissecting Olympic women gymnasts’ mid-air feats to produce an effect of jittery dynamic stillness. In his National Anthem video, Kota Ezawa replaces the high sheen of electronic media with hand-painted watercolor animation of Colin Kaepernick et al. “taking the knee,” using a soft palette and flat surfaces that recall children’s book illustrations—thereby elevating their gestures to a condition of timelessness.

Two sets of photographs dealing with pain and personal identity etched themselves into my consciousness: Elle Pérez’s images of people going through bodily transformations, especially the one of the word “DYKE” being scalpel-cut into flesh, oozing with beads of blood; and Heji Shin’s portraits of babies caught at the literal moment of their coming out. Taken with the collaboration of their mothers, these images show one body emerging from another (form within form again): a squashed purple head contrasts with scarlet blood on white thighs; a furrowed brow emerges from a raw vagina, bloody fist squeezed tight below its neck; a not-quite spherical head at the apex between splayed legs. These incongruous juxtapositions are presented with astonishing directness—a riff on Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, maybe, but from a female photographer’s empathic point of view rather than a male painter’s erotic gaze. For all the gore, I couldn’t take my eyes off them.