Leslie-Lohman Museum and NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, New York

April 24-July 21, 2019

The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum, Miami

September 14, 2019-January 2, 2020

Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

March 5, 2020 to May 31, 2020

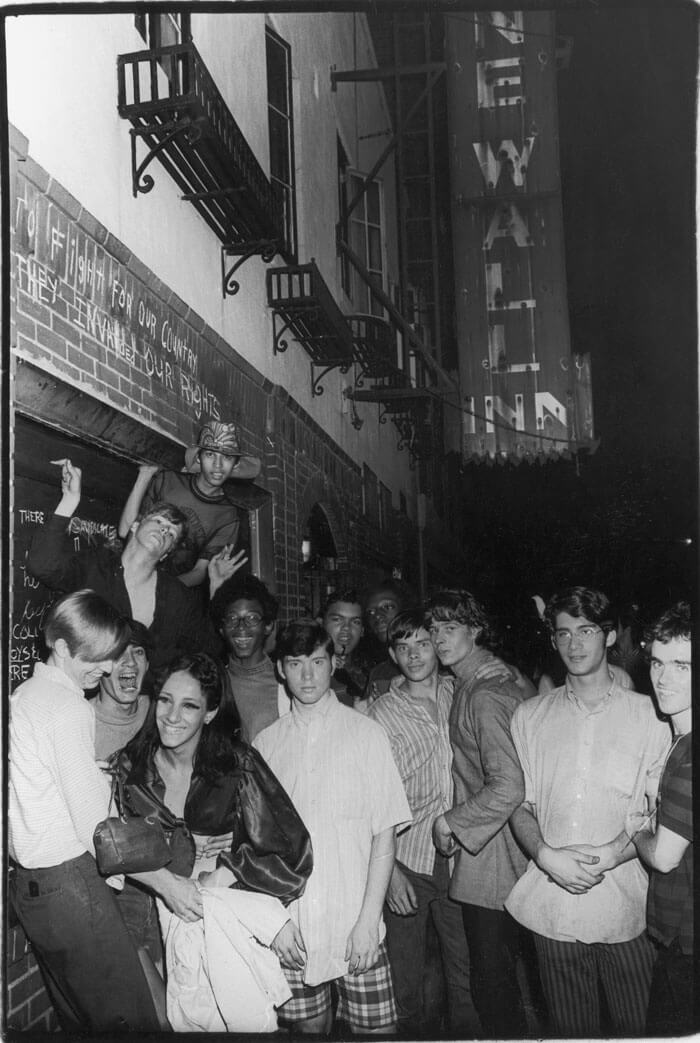

It’s late June 1969, and the young people clustered on Christopher Street look giddy, some performing, others a bit shy before the camera. Neither they nor Fred McDarrah, the Village Voice photographer who shot Celebration After Riots Outside Stonewall Inn (1969), could have known that the riots—the spontaneous result of a few Stonewall patrons deciding to disrupt “business as usual” during a routine shakedown of the Greenwich Village bar—would come to be seen as having sparked a revolution in the gay rights movement, but that spark seems to light their bodies and faces.

McDarrah’s photograph is one of more than 150 photographs, prints, paintings, video clips, and other works that will be on display at the Leslie-Lohman Museum and NYU’s Grey Art Gallery in Art After Stonewall, 1969-1989. Organized in seven thematic sections, the exhibition moves in roughly chronological order from “Coming Out” to “We’re Here,” with “Sexual Outlaws” and “AIDS and Activism” two of the five stops along the way.

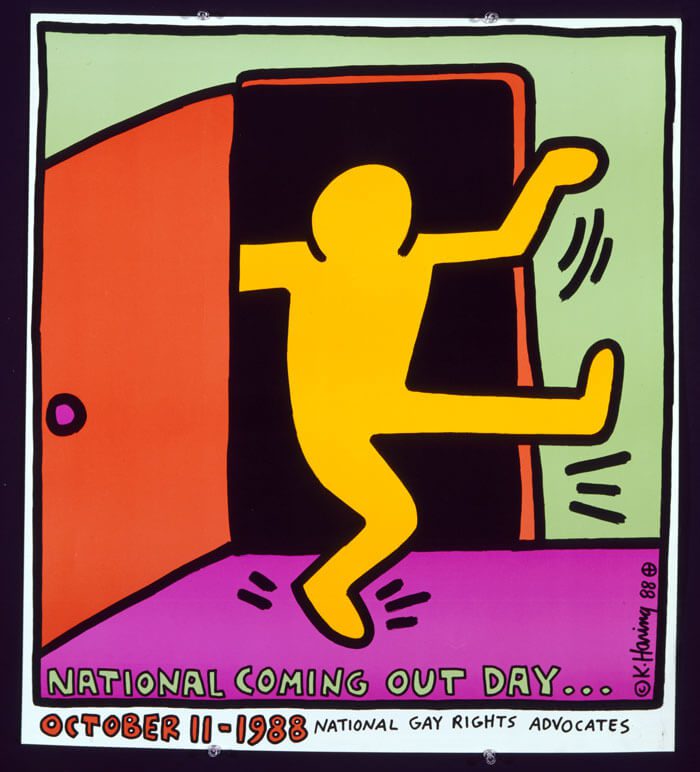

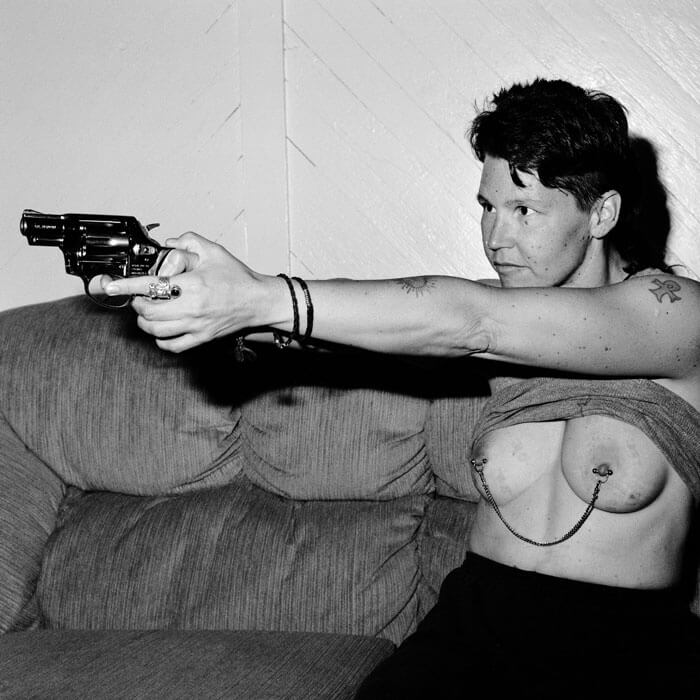

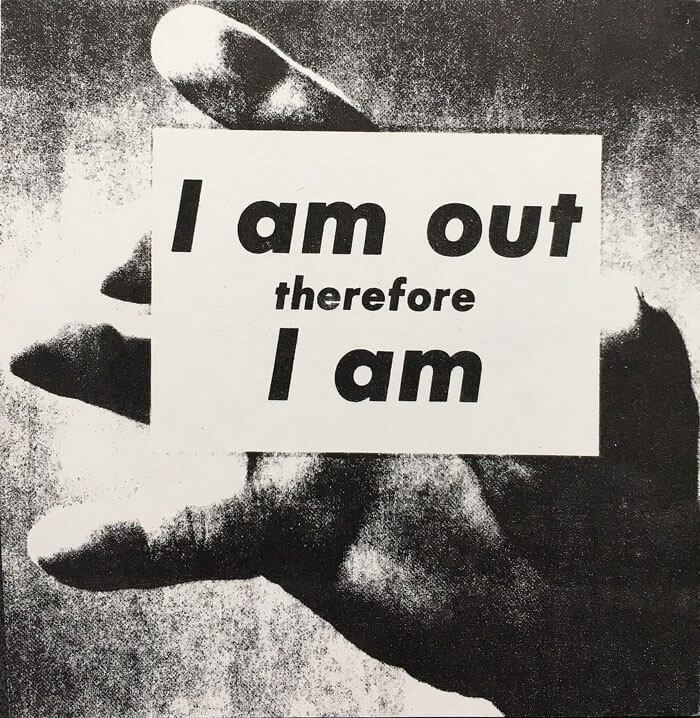

The show is ambitious in scope. Works by familiar names (from Robert Mapplethorpe and Nan Goldin to Andy Warhol and Keith Haring) will appear along with works by less well-known artists, a choice which lead curator Jonathan Weinberg hopes will bring more widespread attention to artists like Morgan Gwenwald and Alvin Bastrop. In the late seventies and early eighties, Bastrop spent hours photographing men on the since-demolished West Side piers, and The Piers (Three Men on Dock) (n.d., 1975-1986) is a gentle image of three nude black men, their backs to the camera, their vulnerability and desire as palpable and tender as their youth. Sunil Gupta’s Untitled #8 From Christopher Street (1976) is another example of the space where documentary photography meets political act. It’s a simple image—two gay men walking down the street—but their pride is evident in their posture, stride, and dress. Of course, the photograph as document is deceptive. In Honey Lee Cottrell’s self-portrait, Bulldagger of the Season (1981), a butch woman in briefs, her shirt unbuttoned, confronts the camera. Conceived as a response to the passivity of the Playboy centerfold, Bulldagger is striking not just for its subject’s power, but for her sexiness.

Not all the artists featured identify as gay or queer, and not all aligned socially or politically during the post-Stonewall years. Alice Neel’s huge, psychologically revealing portraits invite a casual, if disconcerting, sense of intimacy that is impossible to experience with the photographs and collages of David Wojnarowicz, an artist best known for the electric scrim of rage with which he met homophobic responses to the spread of AIDS.

Art After Stonewall and the accompanying catalogue promise to bring a critical, yet intensely personal lens to the story of Stonewall’s impact on the arts—and to the indelible impact of artists on this pivotal era in the gay rights movement.