form + concept, Santa Fe

September 28, 2018 – November 17, 2018

What does it mean to make landscape paintings in 2018? Just this morning I was reading the recently issued UN Climate Change Report about coming food shortages, growing wildfires, and other ecological disasters. After digesting this and thinking about our nation’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, again I ask, what does it mean to be making landscape paintings now? In his first solo show with form & concept, Matthew Mullins talks nature. His focus is not on our impending self-created doom but on society’s disconnect from the natural world, which, in truth, brings us to where we are today. With so many different bodies of work in the exhibition, it’s a stretch to hold this theme as an umbrella for the entire show. There’s a blending of Euclidean geometry and pastoral mountain settings that succeeds in some paintings but not in all. Canopy, one of Mullins’s paintings that works, consists of a rendered aspen cluster, embedded starburst pinstriping, and a pair of wavy, interlocking patterns that simultaneously create a world inside the canopy and offer a view on to the horizon. The implied order and structure of the paintings work through the use of pinstripe patterning, but it can also flatten out a painting when the patterns are not integrated Call it a cage or a prison, the pattern overlay ends up as a container for the landscapes.

A set of observational watercolors of New Mexico peaks, while intimate in scale, possesses a much greater presence than Mullins’s other paintings. They’re honest, without gimmick, and irregularly shaped with a patterned edge that speaks well to Mullins’s past interest in quilting. The rich atmosphere in Shasta has the distant, pale blue peak floating along with the clouds above the tree line. The watercolors deserved more spacing than they were given (overhanging is a constant problem I see while gallery hopping in Santa Fe, and it flattens the work).

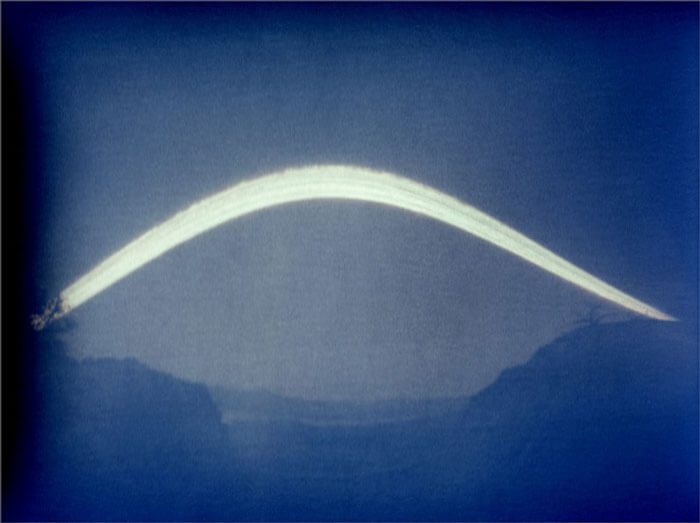

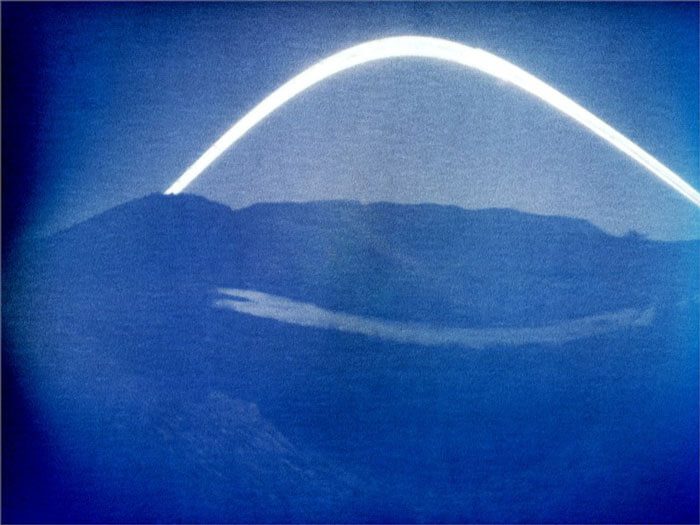

The highlight of the show and what really brought me in to see Mullins’s work is his set of pinhole solargraphs that are closely aligned with the show’s title, The Sun in Our Bones. To fully understand these solargraphs, you should know that Mullins hikes deep into northern New Mexico backcountry to set up his pinhole cameras that risk being destroyed by extreme conditions and wildlife. The works are outside of the studio, products of overlapping performative elements of endurance and mapping along with chance metrics rooted in game theory. Not all pinhole cameras survive the six-month timeline required to produce one of the images. Chama River looks to be situated at a bend in the river south of Abiquiú Dam and at the foot of Trujillo Hill, which is also the dividing line of the Colorado Plateau and the Rio Grande Rift. Mullins captured a stunning solar arc that travels from out of the frame (east) to behind the Jemez range ridgeline (west) with a shimmering reflection in the Chama River. The weight of the work isn’t so much in the backstory of how it’s made but rather the solargraph’s ability to visualize an archive of sun movements over a period of time. Every passing day, the sun burns a line in the paper—and the accumulation of days as lines begins to stack after months. That widening line arcs as Earth spins on its axis and revolves around the Sun. As the seasons change, this expansive cosmic pattern of stacked lines reveals the striated form of something so close to us and familiar: the rings of a tree. On top of this, the softness of Prussian Blue only adds to the ethereal quality of Mullins’s solargraphs. Mullins’s exhibition is ambitious, problematic, and the talent is visible. The Sun in Our Bones is not to be missed.Walking to my car after the show, all I could think to myself is how would the modernist painter Emily Carr, whose work reimagined the West, approach the landscape in 2018? How do artists embody something relevant to their time through a well-worn and exhausted trope? It’s a question worth asking.