Capturing scenes of quotidian life and military infrastructure, Zoe Leonard’s photo book and The Chinati Foundation exhibition underscore a borderlands reality: an unstoppable river runs through it.

“Never call it the Sleepy Rio Grande. Always call it the Silvery Rio Grande.”

Thus admonished the singing cowboys on the high-wattage American “outlaw” radio stations located just south of the flowing borderline between Texas and Mexico in the 1930s. The maxim encapsulates American culture’s historically romanticized notion of the Rio Grande, or Rio Bravo as it is known south of the border.

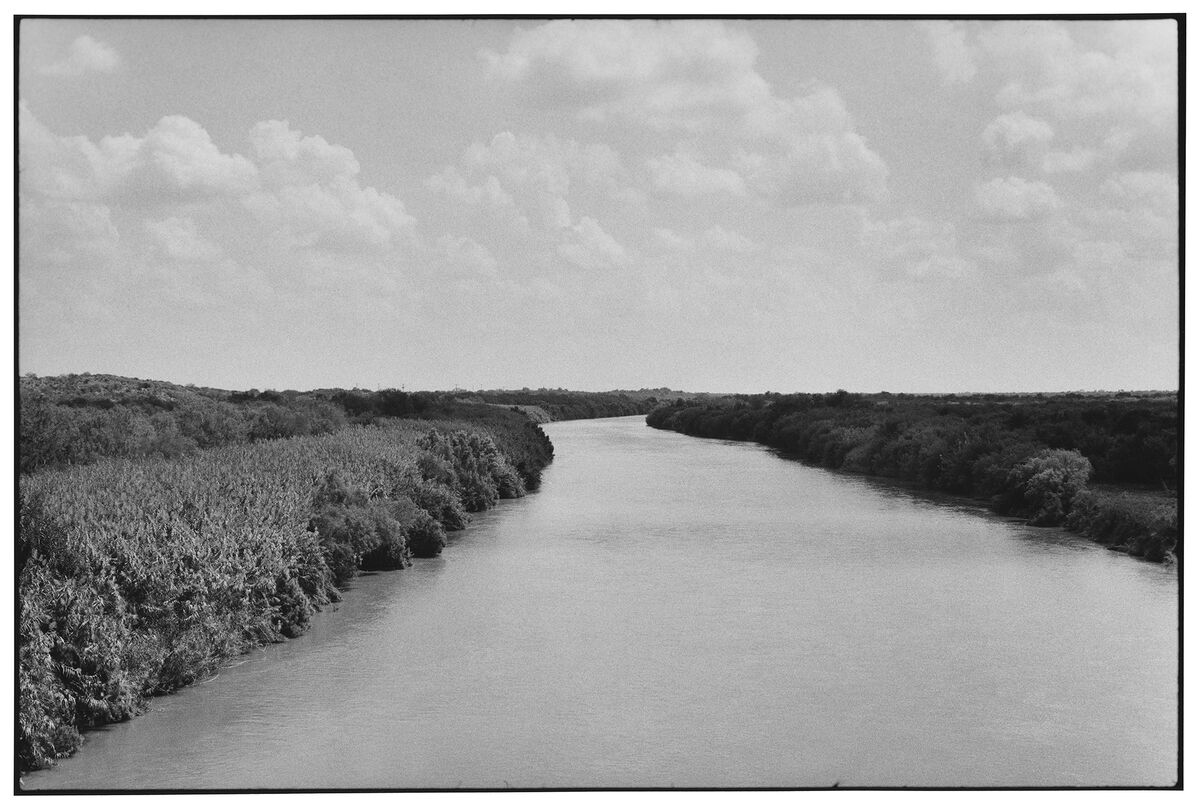

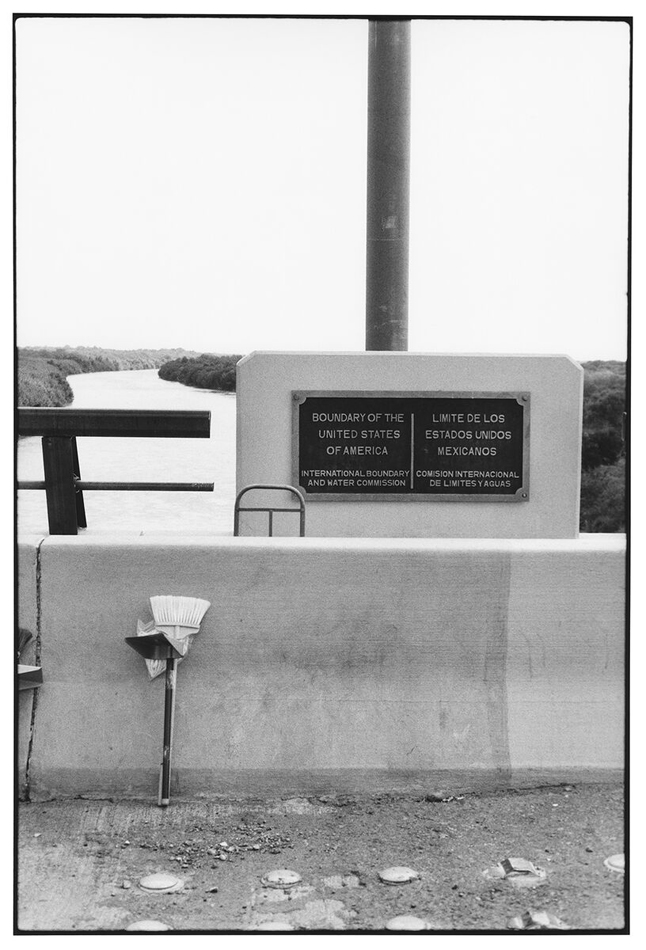

Today, of course, amidst its fraught and highly charged environment, the Rio Grande is rarely described as silvery. Occasionally, drought renders parts of it not merely sleepy but invisible. And while photographer Zoe Leonard was not the first to deflate the fairytale, her international photography project is surely among the Rio Grande’s most exhaustive—as evidenced by her recent Hatje Cantz monograph, Al río / To the River, and her current exhibition of the same name at Marfa’s Chinati Foundation. Leonard spent seven years roaming and photographing the river, from 2016 to 2022. Her stated objective was to explore the results when a body of water is requisitioned as a political force, an international boundary between two worlds burdened with the loaded and arbitrary signifiers of “first” and “developing.”

At last the pressed-into-service, neutral-among-nations ribbon of life-giving water escapes into the Gulf of Mexico.

The project’s book iteration is a two-volume set, the first comprising Leonard’s images and the second a collection of texts and conversations about the border river, edited by Marfa poet Tim Johnson.

The photography volume opens with a prelude of eight color images that allow the river’s water to speak for itself, gurgling, bubbling, frothing, and swirling in close-up frames that capture the precious resource in moments of innocence and joy.

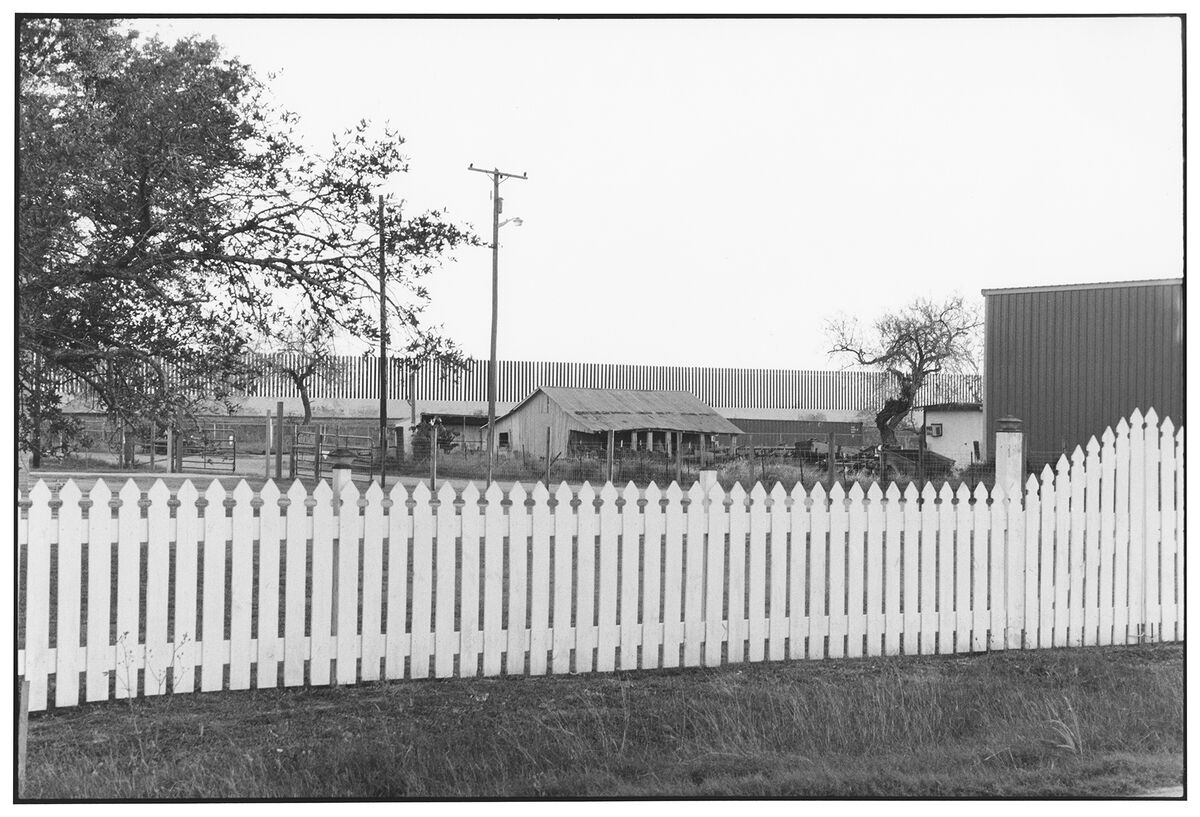

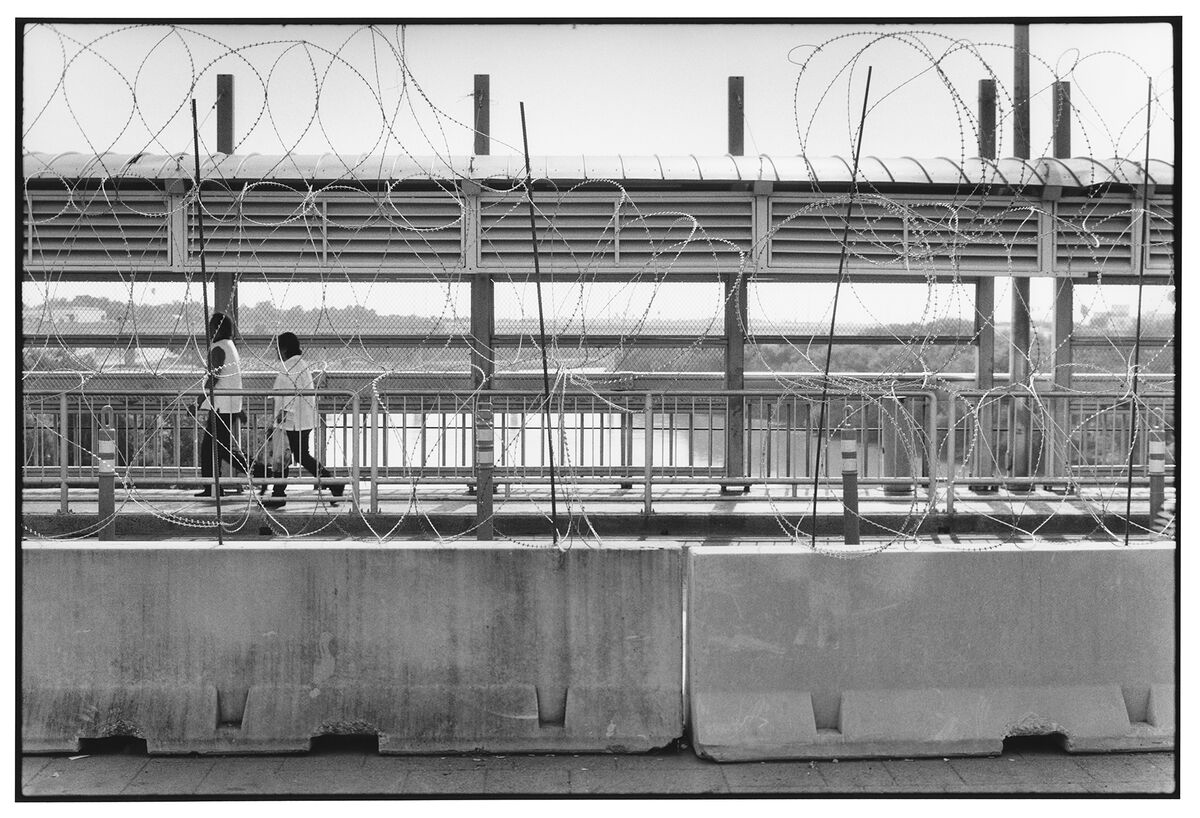

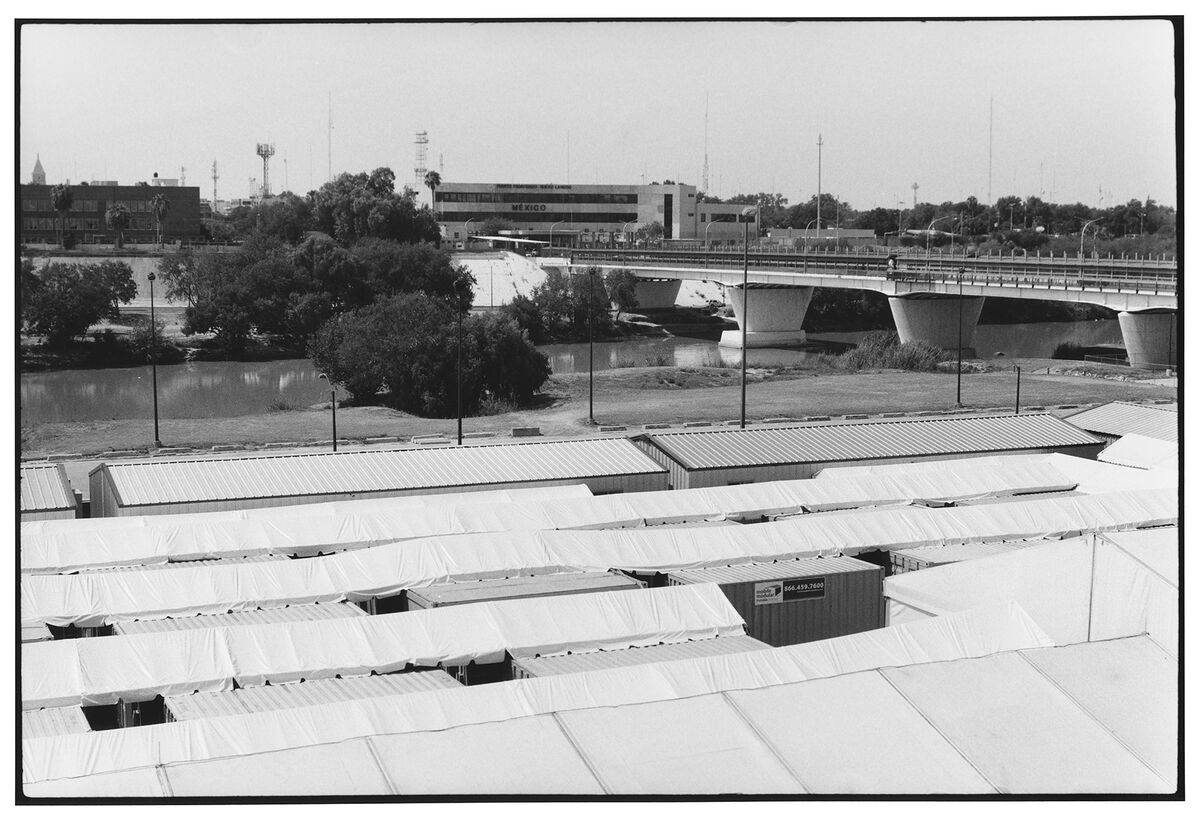

As the book moves into its body of mainly black and white photographs, natural, riparian features and everyday human activity appear alongside militaristic infrastructure and hardware throughout the hundreds of images that begin in the desert just west of El Paso. Grouped in passages of imagery that establish varied narratives, the riverine scenes unfold in dramas both small and personal and huge and universal until at last the pressed-into-service, neutral-among-nations ribbon of life-giving water escapes into the Gulf of Mexico.

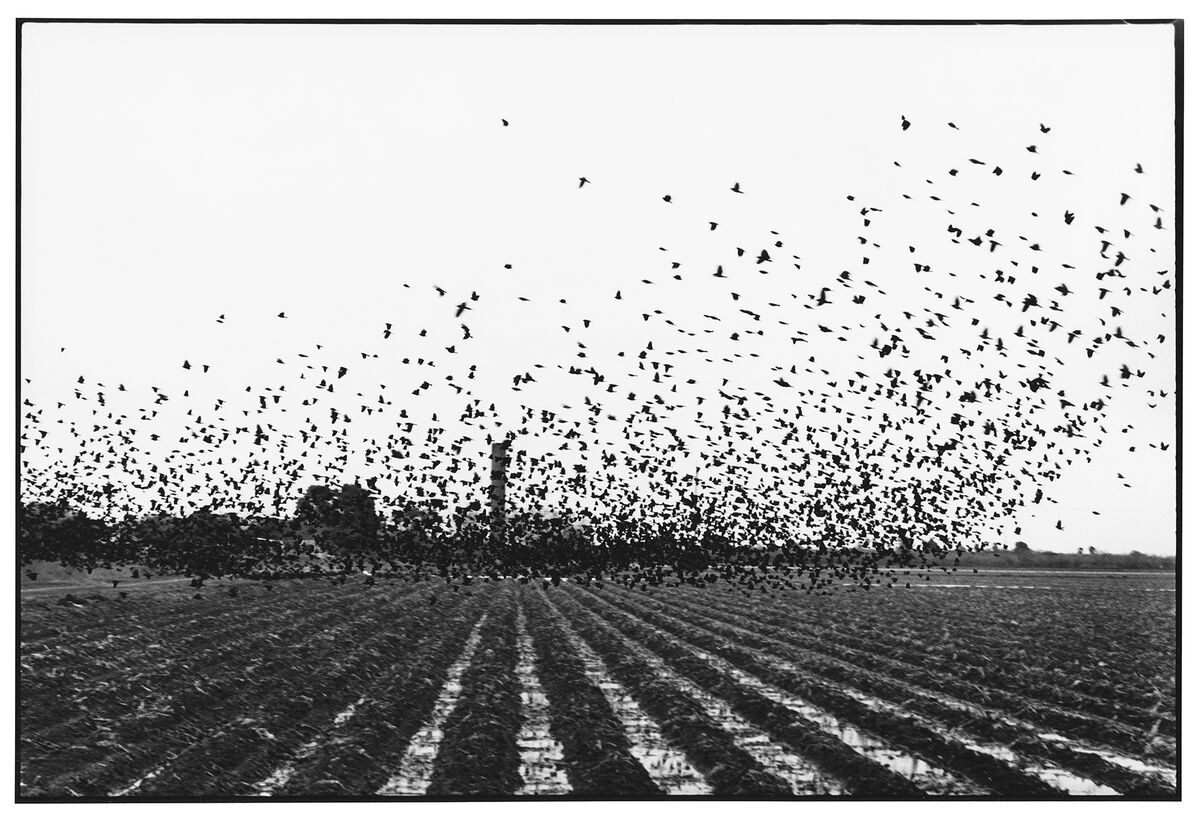

Along la frontera, regular life rolls on. Families frolic in the border river, their pickups and sedans parked on its banks. Ferry operators pull cables by hand as they transport border crossers and vehicles at the Los Ebanos-Diaz Ordas Ferry. A lone rider on horseback evokes a timeless saga. Birds pay no heed to fabricated dominion.

Between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, the river is channeled into a concrete girdle, to ensure that it can no longer change its mind and slice off a chunk of one nation and award it to the other. And thus begins a 1,200-mile, intermittent array of chain link, razorwire, warning signs, surveillance gizmos, detention facilities, and other structural apparatuses and equipment designed to arrest the passage of wayfarers on an often desperate and dangerous trek to the north, in search of economic opportunity and freedom from social and political instability. U.S. Border Patrol vehicles lurk on the levees. Airboats whirr and skim. Trucks drag tires, smoothing the soil to capture immigrant footprints. And almost randomly, sections of border wall are stabbed into the earth like tines of giant combs.

The second volume of the Hatje Cantz set may offer the most unexpected takes on the unique culture and history along the Rio Grande this side of The Late Great Mexican Border: Reports From a Disappearing Line (Cinco Puntos, El Paso, 1996), which, along with the anticipated and necessary takes on smuggling, immigration, and border life, includes such surprises as an account of the ways in which the imposed border zone affects plant life, specifically the Sonoran night-blooming cereus cactus.

The images portray a river environment that struggles with fierce grace and rebellious beauty against the human hand that inflicts its wounds.

In one discussion in the new volume, “Borderlands Image Environment: A Conversational Bibliography,” Esther Gabara, Nadiah Rivera Fellah, and Roberto Tejada explore “the role of photography in configuring our understanding of the border.” Opening the wide-ranging dialogue, Tejada notes, “It’s such a complicated and overwhelming issue. We’re in a pivotal moment at the border. On the one hand, it has become hyper-visible, but on the other, it has become marginalized in the national imagination.”

Tim Johnson’s conversation with archeologists Carolyn Boyd and Yuri De La Rosa is a concise primer on border country rock art research that also provides new information, such as Boyd’s recent discovery of brushstrokes that change direction for a figure’s inhalations and exhalations. Josh T. Franco and Álvaro Enrigue offer meditations on bridges that no longer cross the border: a barricaded bridge to La Linda, Coahuila, and a dismantled pedestrian bridge at Candelaria, Texas. Franco muses about the latter in the context of Donald Judd’s work.

Back on the Rio Grande, while Zoe Leonard does not tweak or enhance the river as in, say, the shimmering images of Laura Gilpin, the landscapes in Al río / To the River sometimes evoke a vision of how they might have appeared had colonizers never reached New World shores. From desert moonscape and soaring canyon to palm-lined resaca, the images portray a river environment that struggles with fierce grace and rebellious beauty against the human hand that inflicts its wounds.

And when those photographic captures of untrammeled terrain give way, throughout the book, to scenes of a scarred and embattled watercourse, they serve to underscore the vivid, bracing reality of the border that Leonard so proficiently depicts.

Editor’s Note: Special thanks to The Chinati Foundation for providing installation images from their current exhibition Zoe Leonard: Al río / To the River, which showcases the body of work featured in this article. While Gene Fowler was unable to view the exhibition in person, his insights and reflections stem from his deep engagement with the Hatje Cantz publication of the same title. This note serves to distinguish the two intimately related presentations: the Chinati exhibition and the publication, each of which offers a unique point of entry to the work.