Flagstaff-based artist Shawn Skabelund returns to the storm-swept ravine that birthed his latest show—and explains what a squirrel stick is—in an intrepid studio visit.

A studio visit with Flagstaff-based artist Shawn Skabelund necessitates hiking up the steep, gravel Mt. Elden Lookout Road, then along the single-track Down Under Trail above a ravine in Coconino National Forest. I carry my water bottle in one hand and phone open to my recording app in the other; our trek includes a conversation. Skabelund carries a stripped and sanded quaking aspen pole from his recent exhibition, Their Largeness Passes Through Me at the HeArt Box Gallery in Flagstaff. During our hike, he hopes to return the aspen pole to the ravine, placing it into a fire-hollowed tree trunk.

Since 1993, Skabelund has been creating art actions in the wild, participating in gallery exhibitions, experiencing new places during residencies, and testing his senses and body in performative art. Thematically, he says, his work is about, “Place. And the economy of that place. How it was settled by European colonists or rather unsettled by displacing Native cultures, flora, and fauna.” Skabelund mentions Wendell Berry, and what Berry calls the “unsettling of America,” the effects, marks, and changes European Americans, like his ancestors, have made on specific places. “That,” Skabelund continues, “in combination with the circle of life. From life comes death, without death we can’t have life. That’s always in my work somehow.” Work as varied as it is thematically cohesive.

In his 2017 performance You eat horse through my carrots, the artist lay on the floor of the Coconino Center for the Arts under a pile of horse manure, next to a horse skull, with a bowl of carrots from his garden nearby for viewers to chomp on as they viewed the work. Russ Pryba, professor of aesthetics in the School of Philosophy at Northern Arizona University wrote, the work is “a provocative look at ecological cycles and the interconnection between life/death, growth/decay.”

Knowing flash floods were imminent, he decided to retrieve the stump of the pine; a month later, the rains came.

In 2020, Skabelund’s in situ art actions included questioning the Forest Service’s tree-thinning practices in Flagstaff’s forests by tagging logs awaiting shipment to South Korea with the words “Cut for Korea.” In What Bear Brought Down, near the Schultz Creek Trail in the Coconino National Forest, Skabelund arranged stones and slabs of ponderosa pine bark in a reliquary display.

That pandemic year, while mountain biking along the ravine we’re hiking, Skabelund noticed a large ponderosa pine cut into logs by the Forest Service after a fire. Skabelund decided he’d spend his time in the ravine creating a sculpture park with the logs, which he scraped, cleaned, sanded, and arranged vertically. During the pandemic, the ravine became his in situ studio.

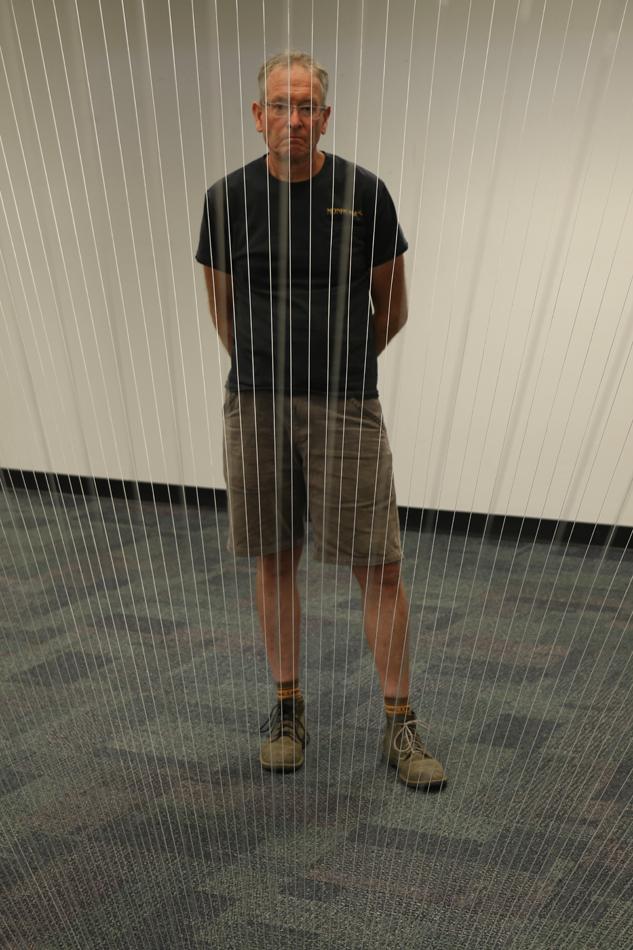

In the spring of 2021, knowing flash floods were imminent, he decided to retrieve the stump of the pine; a month later, the rains came, wiping out the rest of his sculpture park. But Skabelund gained the impetus for a gallery show. In addition to the charred stump-and-aspen pole sculpture, Their Largeness Passes Through Me included a row of slender, charred ponderosa pine trunks (echoes of the ravine sculpture) etched with the hieroglyphs of insect borers; and sculptures of cupped hands—cast in concrete, pine pitch, and rubber—holding ponderosa pine seeds and soil. In an alcove in the gallery, he crafted the installation Re-Creation, with ponderosa pine cones, pitch, pollen, and peeled twigs; sawmill blades and prepared crow specimen; and in a posthumous tribute, his father’s Levi denim jacket.

Born in Mt. Pleasant, Utah, Skabelund grew up in the small logging village of McCall, Idaho. He was one of nine children. His father worked for the U.S. Forest Service. Both parents were foragers. “That’s how I got started collecting, with our family’s huckleberry picking,” he says. His work at HeArt Box included bowls of pollen he shucked from pine cones, hundreds of ponderosa pine seedlings, and just as many squirrel sticks.

“What is a squirrel stick?” I ask, as we hike by primrose, rose hips, aster, firecracker penstemon, and an Abert’s squirrel. In the spring, Skabelund explains, the trees suck water up from the ground to create sugars. The squirrels will find a sweet tree and sit for hours stripping bark from twigs to get at the sugars. When Skabelund finds a pile, he picks them up. “I’ve been collecting twigs for nine years. I’ve got two dozen boxes full.”

The landscapes I live in are my studios, but rarely do I use them as subject matter.

“The landscapes I live in are my studios,” he continues, “but rarely do I use them as subject matter, nor do I draw or paint in them. Instead, I wander in and observe, spending years collecting indigenous natural materials to create ‘new landscapes’ and new forms.” Since he stopped teaching in the art department at Northern Arizona University thirteen years ago, he says, his work has become “more organic.” And by making art with abundant natural materials he collects, Skabelund continues, “I get to witness the public’s surprise and wonder about what I’ve done.”

When we reach the ravine, Skabelund discovers his aspen stick doesn’t fit into the charred pine trunk. So, he’ll carry it back down, cut it to size in his garage, and try again on another hike. “What I’m hoping people take away from my work is a love and appreciation of where they live, and the desire to take care of and be stewards of it,” he says. He also hopes his work helps people “question things, realize natural materials can be used to create beautiful artwork, and open their eyes about what can be.”

Skabelund’s installation Expanding Home/Place is currently on view in the Riles Building at Northern Arizona University. On September 28, he’ll complete his residency at Wupatki National Monument with Convergence, an art installation with piano performance by Janice ChenJu Chiang in the historic Rock House Garage.