Multi-media artist Ruby Barrientos channels their ancestors and their anger to create spirited paintings and sculptures rooted in the past, but deeply relevant to the present political moment.

RENO—There’s only one free chair, plus the stool Reno-based artist Ruby Barrientos clears off for themself, in the garage-turned-studio. The perimeters of the space are stacked with canvases, glimpses of kinetic faces, and geometric symbols. Barrientos’s new puppy—half Golden Retriever, half basset hound—whimpers on her purple leash. “She doesn’t like being in the garage. There might be too much energy in here,” Barrientos says, laughing.

The space does pulse. Symbols and lines move across every surface in the studio, from canvases to carvings. Barrientos, who uses they/them pronouns, gestures at a large sculptural piece, a wood-cut, epoxy-filled face—this is one of what they call their “deities.”

“I showed at Reno City Hall because I was the city artist in 2021,” Barrientos explains. “I wanted to show new work and had all these faces I’d drawn. This was the catalyst to making my work bigger.” Part of the Nuwave Mayan: Ancestros series, the deity is nearly four feet tall and can be illuminated from behind via LEDs. The effect is incandescent, something akin to stained glass—a fitting nod to other religious artifacts.

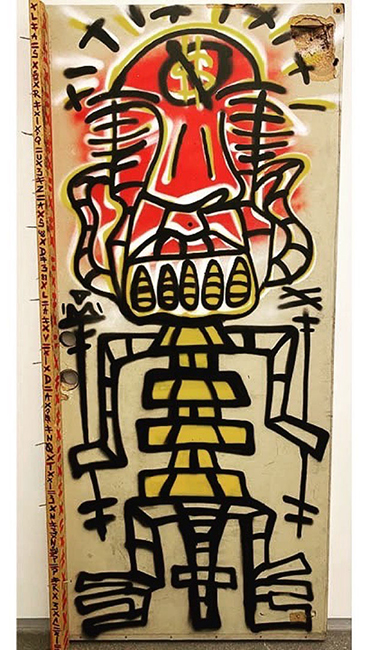

Barrientos isn’t shy about experimentation, and the past few years have seen notable shifts in their craft. Inspired by reconnection with their ancestral roots, enraged by the racial unrest in 2020, and driven to connect with the Reno community, Barrientos has pushed for bigger, bolder work. While earlier pieces fuse ancient symbolism and modern techniques, like spray painting, to bridge the gap between past and present, their newer works draw on ancestral strength to speak truth to power in today’s political climate.

Barrientos unrolls a dirty red banner on the studio floor. A long deity head runs down the center, and there are scraps of language scrawled all over. The edges have been burned, leaving gaping black holes. The gathered dust only adds to the effect.

“I felt called to make this in response to the crime happening to Black and Brown people [by] the police,” Barrientos explains. “This is part of a series, Los Rezos De La Revolución—Prayers of the Revolution. I treated them as artifacts and wrote all over them: things that were happening with the [U.S. presidential] administration, things told to us to make us think we’re all equal. These pieces were meant to educate people and make them question the status quo. That’s why I burned them, to show that people of color have been through so much, but we’re still here, we’re still fighting.”

Back in 2020, such blatant declarations of struggle and frustration were new for Barrientos. “This was kind of my first step into political art,” they say. “I was getting very involved and active in supporting the local community, marching. It was a process of me decolonizing as well.” They took inspiration from Basquiat and Malcolm X, “using information and imagery to get people to look closely.”

This formal experimentation and topical expansion has fueled Barrientos’s latest public piece, the largest undertaking to date, Hijo De Su Bukele. The sculpture was created for a group show at the Nuwu Art Gallery in Las Vegas curated by Geovany Uranda, Cesar Piedra, and Scrambled Eggs. Barrientos pulls up a picture on their phone: it’s a pyramidal structure with a deity projected high above it. The material is stylized to look like concrete and plastered with garish graffiti phrases that bleed into one another. Only telling snippets are legible: “disinformation,” “arbitrary,” “favors 4.”

“This sculpture talks about the El Salvadoran administration,” Barrientos says. “The president calls himself the ‘CEO of El Salvador.’” They shake their head. “He’s like a Trump. They have a state of exception there—anyone they suspect of being a gang member gets locked up, and there’s no due process. That’s what I talk about in this piece. I wrote all over it to make a representation of what’s happening, to make people curious.”

Barrientos, who was born and raised in Reno by Salvadoran immigrants, sees their burgeoning political voice as a privilege. “I didn’t have to grow up worrying about gangs. I have this opportunity to talk about it. I do see the other side of the coin because a lot of people are okay with what’s happening because they feel safer since lockups. But at the same time, it’s not a sustainable thing.” They’re looking toward the future, thinking about the next generation.

For Barrientos, creating a continuous circuit between self, community, and ancestry is both a personal and political practice.

The Hijo sculpture itself was a group effort—Barrientos partnered with BFA students from the University of Nevada Reno to create the eight-foot-tall finished product. The piece was on display at the Holland Project Gallery before moving to Vegas to join the Nuwu show, Hija/e/o/x(s) de Su, which brings together works from Latinx communities in Las Vegas and Reno and runs until December 7, 2023. As Barrientos sees it, local shows are opportunities to integrate traditionally white spaces and forge connections—they have a new show inspired by folk art, Trascendiendo Fronteras, at the Northwest Reno Library until October 29, and another exhibition at Holland Project, Taking Space/Tomando Espacio, through December 28.

They attribute their deep connection to their ancestral culture to a 2017 trip to El Salvador, their first in twenty-something years. “My dad’s ashes are buried there,” Barrientos says. “I got to visit them, and my family. I got to visit the ruins and see the pyramids [and] see artifacts. That blew me away. When I got back, I felt activated. I’ve been going nonstop ever since.”

The imagery from these experiences is clear in Barrientos’s entire body of work: there are thick lines, geometric symbols, and intricate relationships between shapes that evoke Mayan codices. But their work is also a response to colonial erasure. Barrientos, who was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, sees their art as an extension of their spirituality, a renewal of ancestral beliefs and rituals.

“Me believing in and praying to my dad is something my family doesn’t approve of. These things from the past that maybe my ancestors before them were doing, they reject. But now I’m trying to reconnect to those practices.”

Barrientos’s work is both a battle cry and a boon. “There are a lot of the deities in the political pieces,” Barrientos says. “They bring attention to important subjects, but they’re also a symbol of hope. You can come to this and ask for support and strength. That’s what I do in my spiritual practice: I pray to my ancestors, my dad, my creator, and ask for strength. I picture them around me, creating a bubble and protecting me. I see these pieces as the same thing in 3-D.”

Despite the logistical limitations to creating and storing large-scale sculptures, Barrientos is eager to see their work keep growing, literally. They think of the pyramids, technically attributed to the Aztecs, but with so many parallels around the world.

“All these cultures with these structures look interconnected, and they have this grandiose appeal. I think a part of me wants to make work that big because I want it to be in your face.” Perhaps going bigger means a legacy that lasts.

“It’s taking time out of the equation,” Barrientos says. “Letting it continue.”