The paintings and murals of Denver-based artist Ramón Bonilla explore the multifarious uses of the line and all of its subsequent meanings.

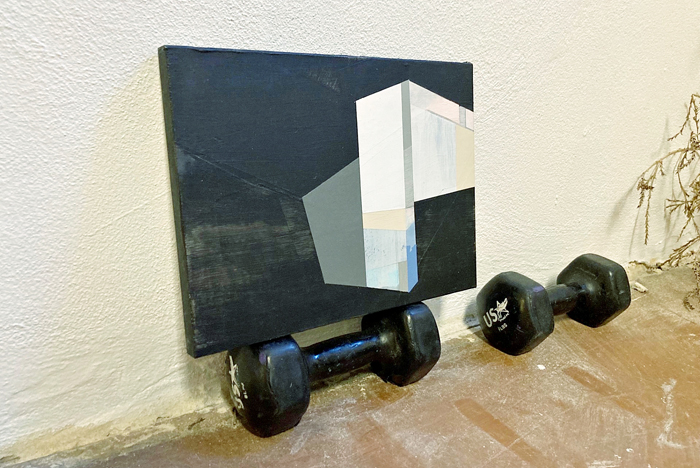

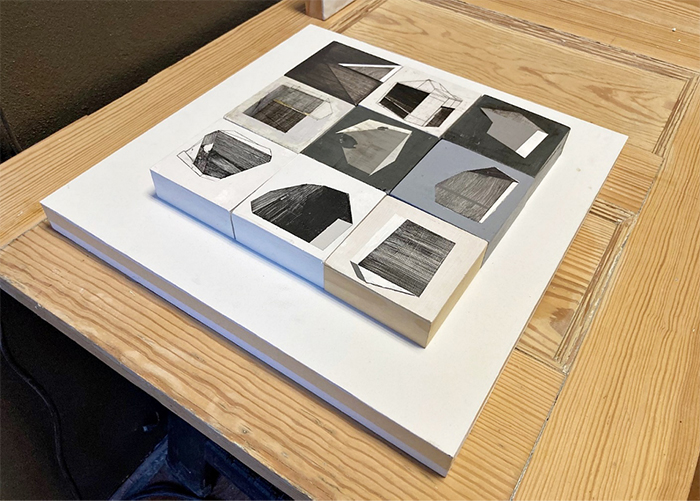

A series of small- to medium-sized paintings rest on the floor and against the walls of Ramón Bonilla’s two-room studio. The space, a former principal’s office on the second floor of Denver’s Evans School, now serves as a workshop for the artist as he creates paintings indebted to art movements and styles such as color field, abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, and minimalism.

While art school provided historical touchstones that would inspire his current practice, Bonilla’s introduction to the aesthetic world had a much more colloquial origin. Born and raised on the island of Puerto Rico, the artist recalls how “my dad used to buy me a comic book called Pumby—I think it was a French comic translated into Spanish—and [it recounted] the adventures of a cat who was a world traveler.” In one particular issue, Pumby visits “an art gallery or museum and enters into one of the Cubist paintings, living inside a Cubist world [where] everything is animated.”

“It caught my imagination,” Bonilla says, “and I went behind my house and started drawing all these geometrical shapes connected with lines. My dad left them on the wall, and they stayed there for years. I think that has a lot to do with my current artwork.”

Indeed, Bonilla’s current artwork does contain geometric shapes and interconnected networks of lines. And while his first comic-inspired painting might be lost to time, it’s not difficult to imagine how central the experience was to his development over the years.

The artist, a former RedLine Contemporary Art Center resident who is now represented by Denver’s Space Gallery, moved from Puerto Rico to Connecticut in the late ‘90s to work as an exhibition designer for the folk arts program at a community center in Hartford. After bouncing between Connecticut, New York City, and Puerto Rico for several years, Bonilla relocated to Colorado because of familial connections.

“When I moved [to Denver], I noticed that the culture and identity of Colorado revolved around the outdoors and the mountains.” This heightened attention to the natural world became a part of Bonilla’s work, and he began to engage “the tradition of landscape,” but in a manner that “related to abstraction and minimalism. To landscape in a different way,” he says.

“I began hiking a lot,” Bonilla recalls. “When I lived in Puerto Rico, I hiked as well, but it was a completely different geography.” In order to process the distinctive landscapes and hone his skills of attention, the artist took his notebook with him on these hikes, which allowed him to “define lines and shapes and textures” from the natural world that he “eventually integrated into [his] work.”

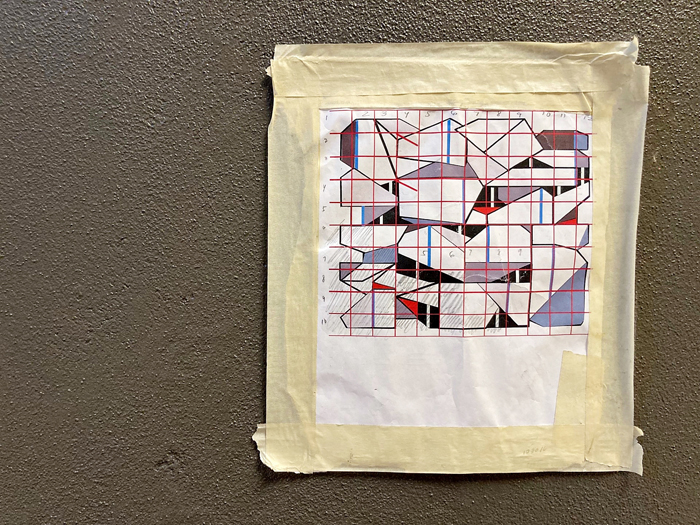

But to landscape in a different way required more than mimicking or representing patterns he viewed in nature. It meant that Bonilla once again found inspiration in the colloquial, taking aesthetic cues from “old, 8-bit video games where one plane was divided into fields of color with blocks designating components, such as a mountain or a tree. They were abstractions synthesizing the landscape.” Specifically, Bonilla references the game Battlezone, and the manner in which “vector graphics shaped the linear landscape.” In this way, Bonilla’s visual idiom for landscapes developed through first-hand immersion within those environments, as well as antiquated, hard-edged digital renderings of those environments.

“I’m not trying to replicate what I see or experience,” the artist explains. “I take certain features from an environment—small things like lines, diagonals, levels, and elevations—then create a space with my visual language where I express myself with those different elements. That’s what I go for in my work.”

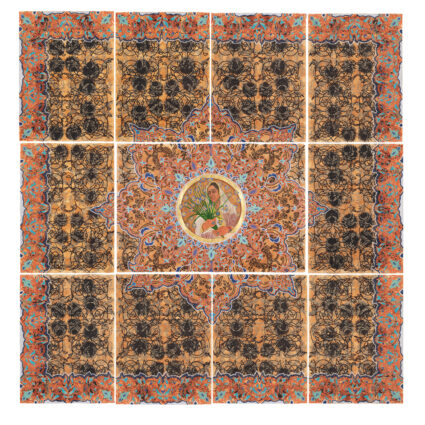

More recently, Bonilla has been preparing for his solo show The boundary lines have fallen in pleasant places for me at the Arvada Center, which opened June 8 and runs through August 27, 2023. The show consists of several paintings and two large murals composed of vinyl and tape, which highlight lines and the spaces created by their intersections.

The show’s title is inspired by Psalm 16:6 in the Old Testament, which, Bonilla says, addresses how “Jewish people would survey the land, dividing it with rope or cord.” Moreover, the artist notes that the psalm references “a coexistence between the visible and the invisible,” which he believes is a central aspect of his art practice.

Like much of Bonilla’s artwork, the title of his solo show carries personal meaning.

“It also reminds me of my grandfather. He was a farmer in Puerto Rico who passed away years ago. They divide land down there,” he says, “using cuerdas—which means rope—to organize [the land] according to lines that they would lay down. I thought that it had something to do with drawing, especially when I’m creating murals with tape, which is mostly lines. So I was thinking about the concept of dividing a wall into different coordinates and the relationships between them.”

Of course, the artist knows boundary lines have also been used for insidious purposes, such as redlining. “Being a person of color, I’ve had to deal with and understand those issues—social and political issues of where one can dwell, wars [predicated upon] land ownership, and how those things change through time.”

Bonilla takes pleasure in the varying messages and meanings of his show’s contradictory title. “I like titles that are open so people can interpret them differently. There are so many things that the basic unit of the line can do in terms of the physical, spiritual, or political. It’s fascinating to me how so much is determined by it.”

Bonilla appears intent upon following those lines and their proliferation of meaning within and through his artwork for years to come.