Nick Larsen, who gives a talk about his Nevada Museum exhibition on Thursday, April 4, explores an invisible history through collage by “pulling from what already exists to visualize something that doesn’t.”

1.

I first saw artist Nick Larsen’s collages at the opening of a group show at Best Western, an artist-run gallery in Santa Fe.

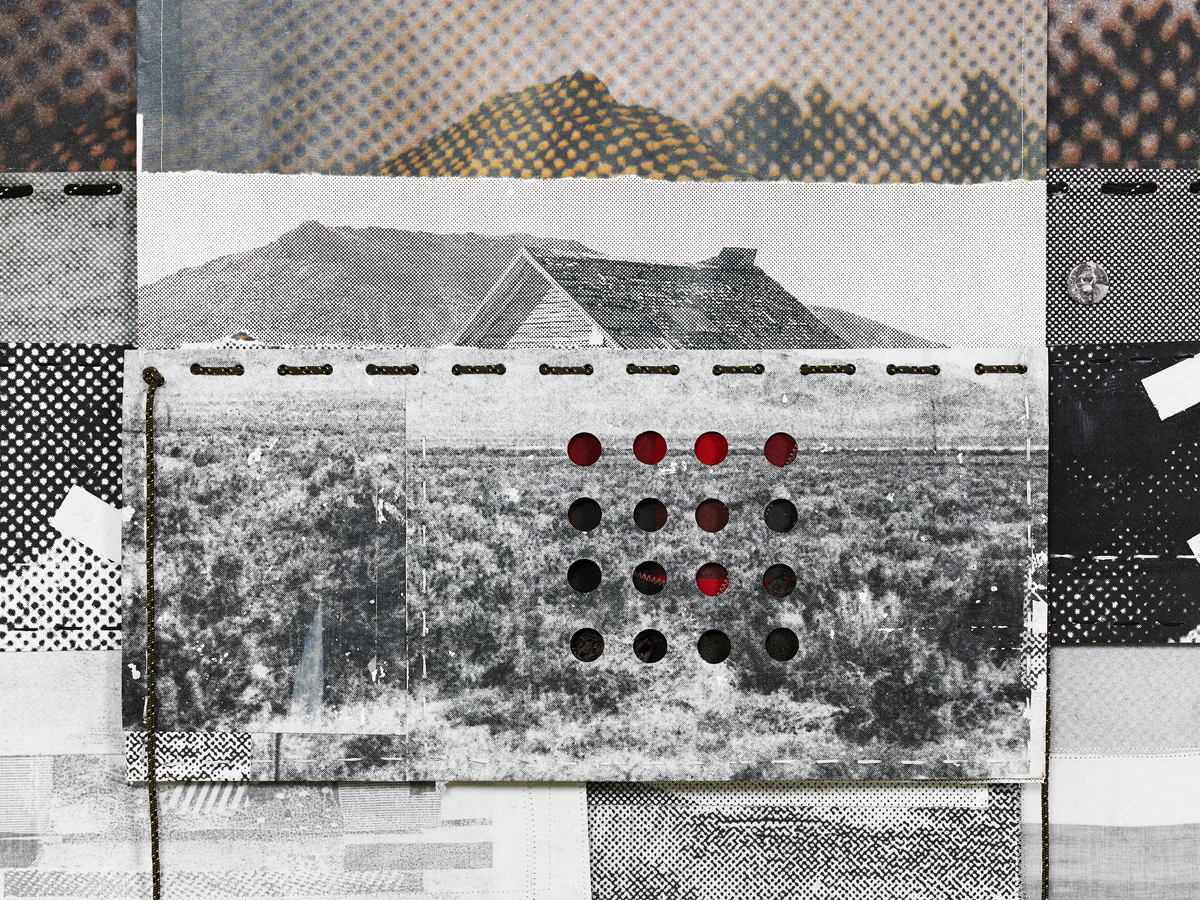

Old Haunt (Every Part of the Buffalo Check Shirt) was hanging next to Old Haunt (New Subdivision). Larsen told me to feel free to touch them.

The layers lifted easily—a photo of an isolated house in a desert landscape (printed on fabric and stitched through with black cotton cord), an abstract landscape in gray, then another.

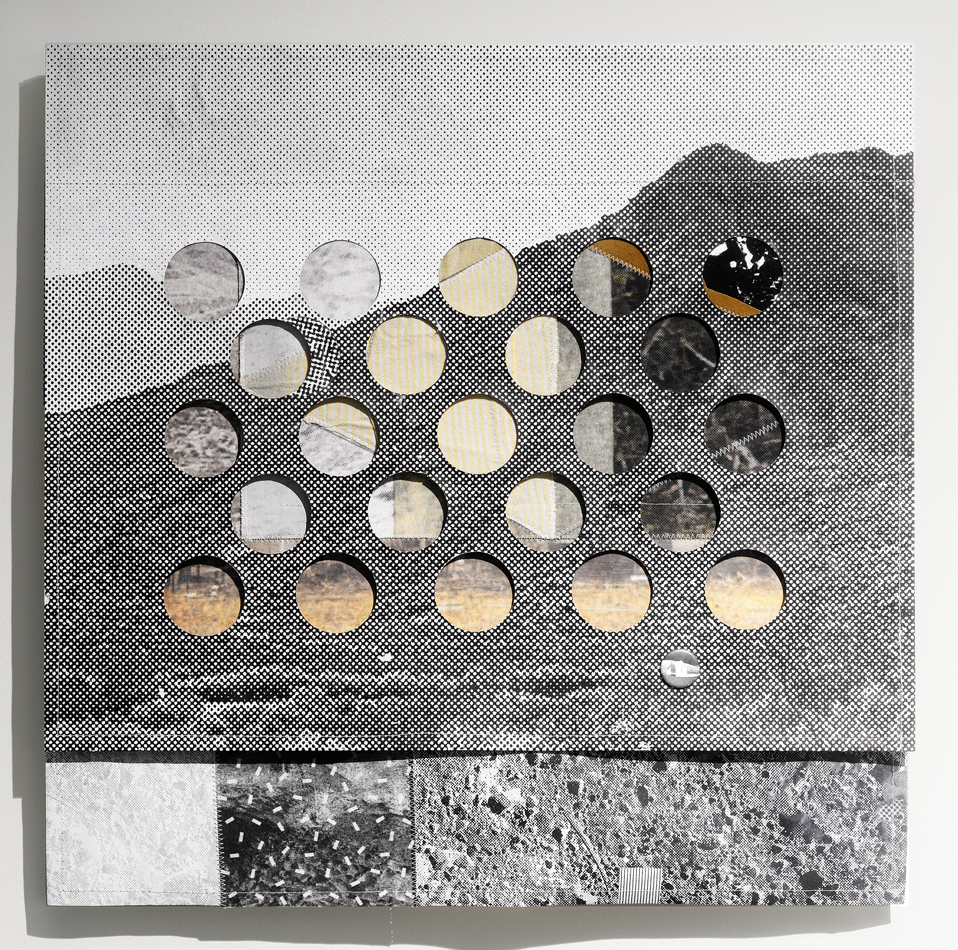

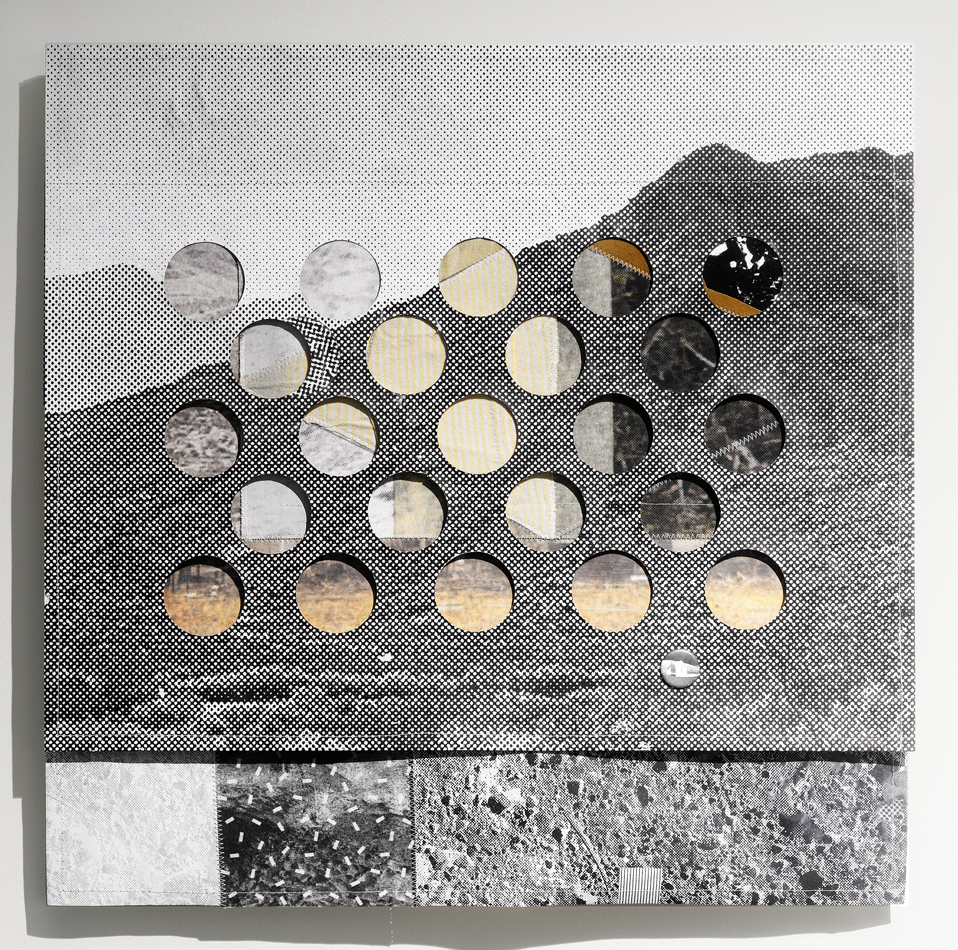

A grid of hole punches on the first layer revealed circles of the one beneath. He calls these gestures “excavations.”

The artist says he deliberately uses the same dimensions for each collage and the same width for each layer, so he can move or replace pieces easily.

“Which reinforces the idea that these collages are speculative. They are all possibilities, but none of them are definitive or fixed.”

2.

Shortly after, I visited Larsen’s studio. Collages were attached loosely to one wall, fabric folded neatly underneath them, models and references thoughtfully aligned on the desk.

“My studio is very small. I have to think about the footprint that things need because these things have to become part of my life. And my life has a constraint of space.”

Larsen’s first sculpture in graduate school was a lean-to structure made with a tarp he used moving from Nevada to Ohio.

“Then, I got interested in this idea of constraint… what would happen if I had to make a second sculpture out of that same material? So, I deconstructed the lean-to and made a poncho for myself. Then, I cut the poncho apart and made a series of bandanas out of that. And then, I cut the bandanas apart and made a series of patches. Each of those iterations holds the gestures and marks and history of the one before.”

The constraint became generative.

“The idea of making do forces a kind of resourcefulness. It forces you to see potential where you are and with what’s at hand.”

3.

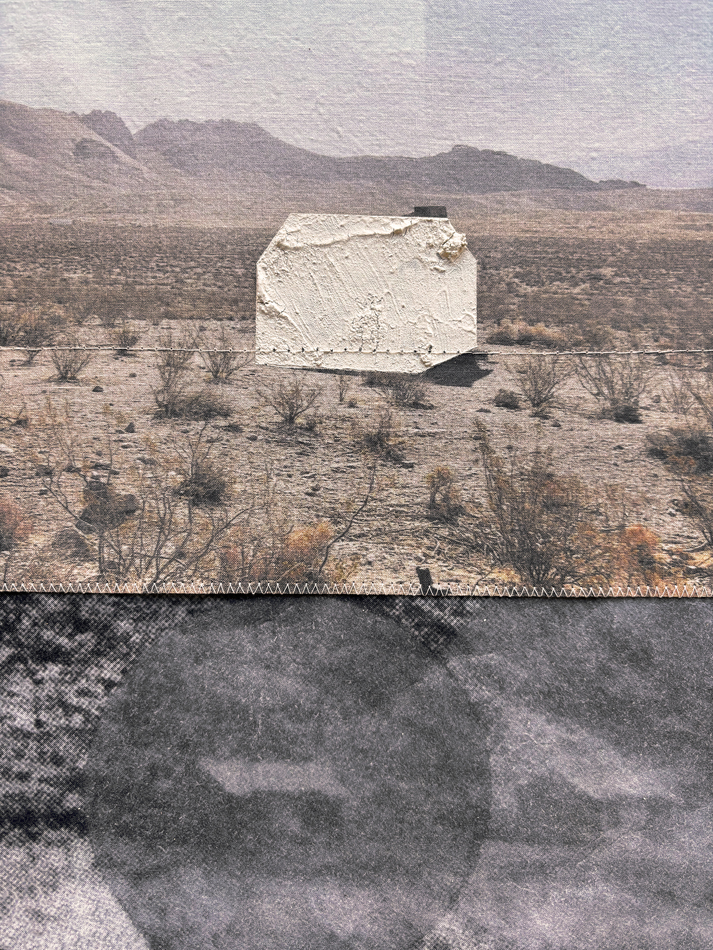

The concept behind Larsen’s recent work developed on a drive through the Nevada ghost town of Rhyolite. He saw an abandoned house on the side of the road and stopped to look more closely.

“I began taking photos of this house because it was so iconic in its shape—like if a little kid was drawing a house. The structure sits on this bit of flat desert basin without any neighbors around. No trees.”

Larsen had learned that, in the 1980s, Fred Schoonmaker and Alfred Parkinson had planned to develop Rhyolite into Stonewall Park, an inclusive gay community.

Headlines had trivialized the proposal—”Ghost Town to Become Gay Town” and “Happy Gays Are Here Again”—and widespread homophobia within surrounding communities prevented Stonewall Park from moving forward.

About a year and a half ago, Nick returned to photograph the abandoned house in Rhyolite. Only the roof remained on the desert floor.

“All of a sudden, I felt like I had formed a way to talk about how the project had collapsed, what it means when the environment pushes back on hopes and dreams, and in the case of Stonewall Park, the social environment.”

4.

Larsen’s recent show at the Nevada Museum of Art, Old Haunts, Lower Reaches (on display through July 7, 2024), is arranged into a wall of collage, textile-based models of the abandoned house (in its present, past, and potential states), a large-scale recreation of its interior walls, and an image projection.

The layout was influenced by Nick’s experience working in the field of archaeology, where no single view is adequate. Aerial images, ground details, and artifact photography all capture different elements of a site (both as it is and as it might have been in the past).

Larsen says even archaeological experts disagree on how to interpret what they see—history evolves as the understanding around it evolves.

“It’s when [an interpretation] becomes fact, fixed, rigid that it loses that [speculative quality] and goes from storytelling and possibility to something concrete.”

Old Haunts, Lower Reaches acknowledges the impossibility of truly knowing the past or future of any landscape and goes one step further.

“For me, it’s a question of how do we remember something that doesn’t have a trace, doesn’t leave a marker on the landscape. [Stonewall Park] was just an idea that never came to be. And so how do we, how do I give that a form?”