Galveston, Texas artist Nick Barbee uses the process of abstraction in recounting American history and personal experiences in his paintings, sculpture, and installation.

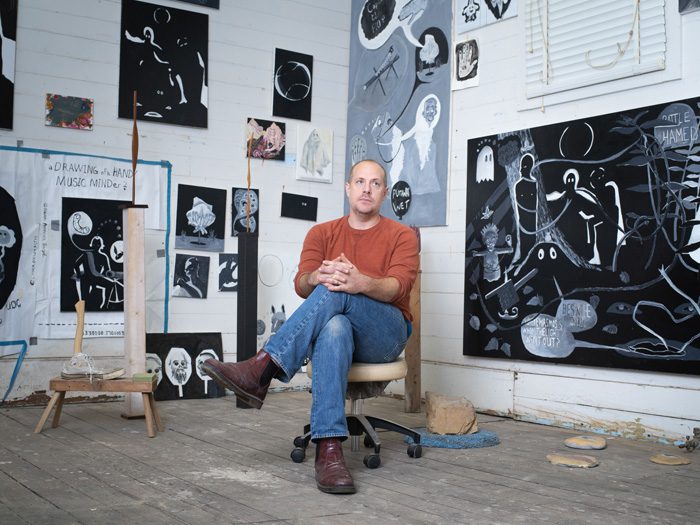

The 1,500-square-foot studio of Galveston, Texas-based artist Nick Barbee is located in the oldest wooden church on the island, constructed before the Civil War circa 1859, that once housed a Catholic girl’s school and soup kitchen. In more recent history, St. Joseph’s Church is rumored to have been the site of the buried head of the Galveston victim of convicted murderer and real estate heir Robert Durst.

“The police searched for the head under the church but never found it,” says Barbee, whose studio practice focuses on historical figures and narratives. “They did find $60,000 in cash—life-changing money—underneath the church, fifteen feet away from vagrants who would sleep under the building.”

It’s safe to say that Barbee, a former artist in residence in prestigious area programs, is firmly planted on the island. Since moving to southeast Texas from the east coast nearly ten years ago, Barbee has worked with the Galveston Historical Foundation in local preservation, a role that informs his artworks, some of which are on view in a ten-year retrospective at the Galveston Arts Center. Barbee, who unearths and recasts stories through “mundane objects,” also draws inspiration from his students at the University of Houston, where he teaches painting.

Barbee grew up near Washington, D.C., where he was steeped in the region’s take on the first several hundred years of American history. Working alongside local historians further reinforces his interest in how the writing of history shares parallels with his artmaking practice.

“Whether it’s a popular or an academic historical narrative that I’m pulling from, I enjoy finding ways to make the more academic stuff more accessible or complicate something that might seem more pedestrian,” says Barbee.

The artist splits his time between his home and studio in Galveston with his teaching post at the University of Houston. In the classroom, he sources inspiration for experimenting with his own artworks in interactions with students attending his painting courses.

“When I give feedback to my students about their paintings and hear myself, I realize that I need to implement it as well,” says Barbee. “What it does for me is that it creates a problem to solve with painting—not just a problem in constructing the image, but a problem and literally, how do you paint that? How does this communicate?”

“For example, painting students might work from a found image, but it can’t be the only tool in the toolbox—so I advise students to ‘complicate’ that,” adds Barbee, who was a core resident at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 2009 and participated in the Galveston Artist Residency in 2011.

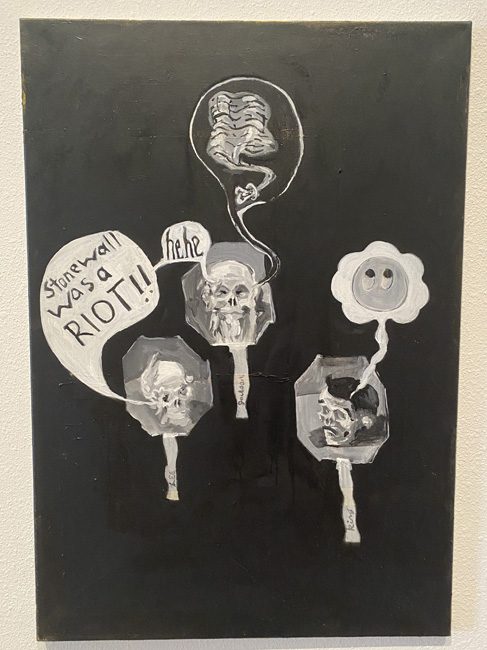

Heeding his advice to “complicate” his paintings, works in progress in Barbee’s studio and finished paintings such as Lee-Jackson-King Day (2020-21) currently on view in his retrospective exhibition Undeniable at Galveston Arts Center include compositions of physical models the artist made in his studio.

“I did a painting about a holiday commemorating Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Martin Luther King, Jr. that was celebrated in Virginia when I was growing up,” he says. “The initial idea was three skulls talking to each other. I know how to draw a skull from memory, but I wasn’t happy with the first painting. So I took my advice to my students ‘to complicate’ the composition by making a physical model using three skulls and put them into character of these three historical figures.”

Even though Barbee is a trained painter, his work often transgresses into drawing, sculpture, and installation. “I’ve never been afraid to let painting morph into a different medium,” he says. “I started embracing materials that I’m not as adept with, such as colored pencils, clay, things like that, because it permitted me not to have to do it right. That expanded my practice into drawing forms, into sculpting forms.”

In his Galveston Arts Center exhibition, on display through April 17, 2022, Barbee offers viewers an opportunity to consider new ways of pictorial representation of American history. His CATO (2011-2022) series of sculptures presents phallic and spindly life-size wooden structures mirroring forms in 20th-century modernist works by Constantin Brâncuși. However, the subject matter of these works is violence—the gangly tops of the pieces are facsimiles of renderings of bodily damage from the trajectory of various bullets used in American warfare, says Barbee.

The name CATO and references to it in other works in the exhibition support Barbee’s interests in reinterpreting historical narratives and challenging the mythologizing of the founding of this country.

”We hear these quotes from the American Revolution, like Patrick Henry’s ‘Give me liberty or give me death,’ and the myth around it is that these men were geniuses,” he says. “What we’re missing from the historical narrative is that they were quoting a play called Cato popular in eighteenth-century enlightenment America.”

Other works in the exhibition, such as the series Good Riddance (2015), further bolster Barbee’s goals of unlearning myths of our nation’s founding and proposing new national monuments. Works in this series depict concrete pedestals renaming historical men with monikers like Tough Titties and swapping controversial figures in our history with ghosts, horses, and ghost horses.

Barbee’s love for history is an all-encompassing aspect of his careers in preservation and education that spills over into his artistic practice, appearing alongside elements from epic stories and autobiographical moments.

“History is an abstracting process,” he says. “The work that I make pulls from myths, historical narratives, and personal histories. I’m trying to approach the ways in which a historical narrative is very similar to the process of formal abstraction.”