Denver-based artist and entrepreneur MarSha Robinson creates elaborate, botanical worlds and runs a thriving business under the moniker Strange Dirt.

The silhouettes of arched window panes crowned in sunburst patterns enclose brilliant swathes of natural light, splashing upon the walls and hardwood floor of MarSha Robinson’s spacious Evans School studio in downtown Denver. The historic building, originally a schoolhouse constructed in 1904, sits one block south of the Denver Art Museum and remained vacant for many years until developers recently converted the structure into a temporary commercial space. Down the line, it will be renovated and transformed into yet another boutique hotel and shopping plaza catering to wealthy clientele. But, for the time being, Robinson—and a slew of other artists—call the Evans School home.

“The school,” Robinson notes, “is a historical landmark: a beautiful, inspiring structure. And I like that there are other artists in this building. You can just kind of feel the energy.” Her studio “has been wonderful,” she says. “It’s elegant and beautiful, and I feel like anything is possible. But it’s also a reflection of how far I’ve come. Being here, I feel like I’ve accomplished something as a professional.”

Indeed, Robinson has come quite far. While she now thrives as a successful fine artist and businesswoman under the moniker Strange Dirt, her journey has been long and circuitous.

“I’ve always known, since a very young age, that I possessed artistic abilities,” she recounts. “But I wouldn’t say that I was heavily involved in the arts growing up as a child.” In fact, it wasn’t until Robinson moved to Colorado just over a decade ago that she began to envision herself as a professional artist.

“I had just moved to Denver and didn’t have a community. I was living paycheck-to-paycheck as a hostess and renting space in communal housing. I was miserable,” she recalls. “But I knew that I possessed something very powerful and needed to share my work with whoever was interested in seeing it.” Around that time, Robinson made the decision to quit her job so she “could make a living creating beautiful things.”

From a handful of original artworks, the artist produced prints and, along with “a new friend [who sold vintage clothing], decided to travel to California and do little pop-ups. We coordinated dates at coffee shops, small-scale markets, and even a vegan restaurant. After coming back from that trip, I felt super high and thought, ‘Yeah, this is going to work for me.’ Ever since that moment, each year has been better than the last.”

“My first, proper art show was at Weathervane Café in Denver just after the road trip pop-ups. I had created a little community for myself, and everyone showed up. I wouldn’t say it was a huge hit, but it was nice to see my work on the walls. I titled the show Strange Dirt because my work is imaginative, botanical life. None of it really exists. I just imagined these strange plants growing from weird soil.”

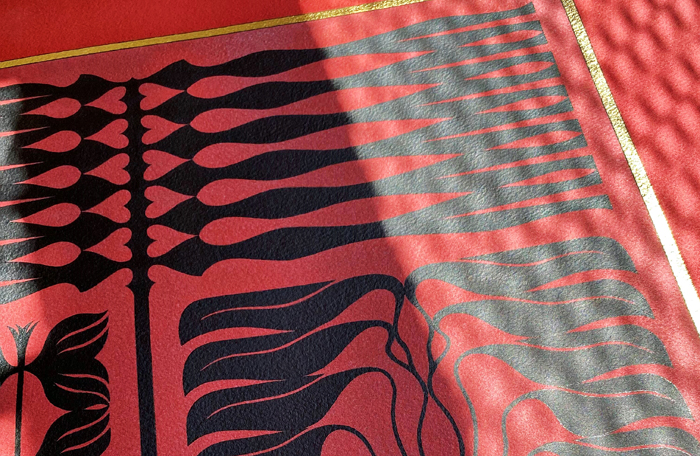

Since then, Robinson’s practice and career have blossomed. “The subject matter of my early work was usually a single flower surrounded by symmetrical, geometric structures.” But soon thereafter, she began “to create something more elaborate,” and her works “evolved into a compilation of many imaginative, botanical forms and shapes.” In developing more intricate, botanical worlds, her artworks became “bigger and bigger. To the point, now, where my artworks are forty-by-sixty-inch wall pieces.”

The artist’s work begins with a loose grid and, in each section, creates organic forms that twist and entwine within those enclosed spaces.

“I lay down the grid work and incorporate more organic and feminine elements within it,” she says. “It allows for a controlled chaos.” And, in doing so, she notes that her artwork combines “the masculine and feminine,” producing a compelling tension. To this extent, her drawings are simultaneously contained and expansive, structured and organic. “There’s a particular type of balance that I try to achieve with my work,” Robinson says. “I don’t want to be on either side of the spectrum. I want to find a middle ground or balance.”

Ultimately, though, Robinson chooses “to create botanical imagery because [it] plays on your aesthetic senses and an inherent beauty that I am attracted to. When you see something as perfect as a dahlia blossom, you feel a certain way. I don’t know if it’s joy or if it’s pleasure. But it does something to you. And I’m trying to achieve that with my work.”

Robinson’s professional career has similarly expanded. Not only does she show with Skye Gallery Aspen, but she also maintains a robust fine-art print business under the Strange Dirt nom de plume. “I am very intentional about the quality of my prints. I take pride in them. They’re archival, and I think they’re beautiful.”

“I know a lot of people,” Robinson says, “who want to be seen as ‘artists.’ They only want to do gallery shows, and they don’t do prints. I admire that choice; it’s pretty noble. But, for me, creating a business around my work helps it become accessible to more people. I could just make originals, only have them hang on gallery walls, and sell them for thousands of dollars. But that only hits a certain demographic. I want my work in people’s homes and spaces. So it was important to branch out as a print business.”

Moreover, she notes, “There’s another advantage to being a business and offering reproductions of my originals. It takes so much time and energy for me to create an original. It’s not a sustainable business practice. If I were to do that, I would burn out, and it would make the creative process more of a job than something that brings me joy.”

As for the future of her art practice and her business, she’d like to develop them both further. With the former, Robinson hopes to “see [her] work move from two-dimensional to three-dimensional space, where the work isn’t just on a wall or surface, but is a structure” unto itself. Regarding the latter, she would like her “boutique prints overseas. I’d like to go international. I’d like to see my work in Japan. In Europe.” If her past professional and artistic trajectories are indicative of her future aspirations, both of these goals appear well within reach.