Lydia see, a multidisciplinary artist, curator, and educator, works with diverse materials in her Tucson studio to explore social justice, foster civic engagement, and broaden access to the arts.

A lovely bramble of desert plant life greets visitors as they approach the front door of the Tucson, Arizona home where lydia see (she/they/y’all) has transformed a small room into a studio space. A camera, weaving loom, and other objects hint at the passions propelling her creative practice that centers “the intersections of art and cultural labor with social justice and civic engagement.”

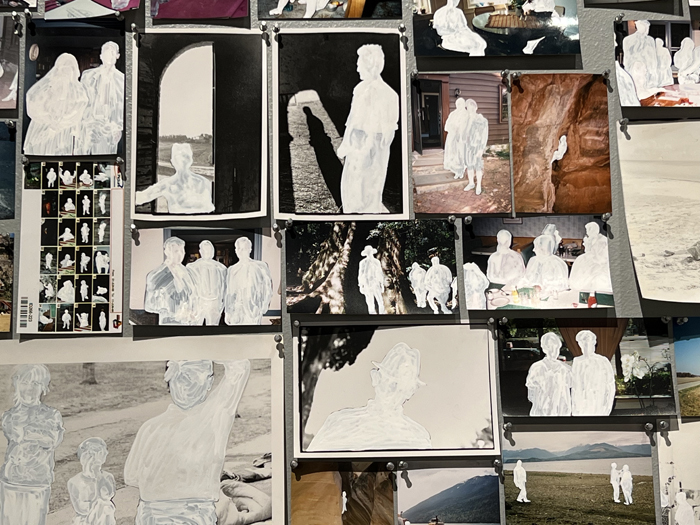

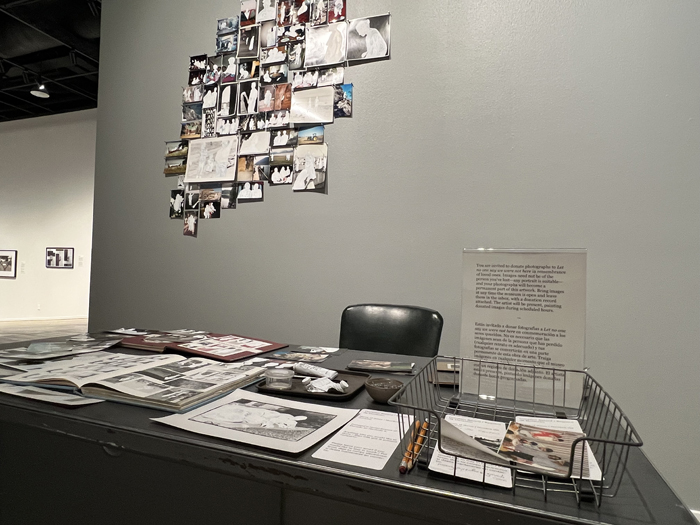

The multidisciplinary artist, curator, and educator—facing a large window along a tree-lined street not far from the University of Arizona—talked about her practice on a Saturday afternoon in July while drinking from an earthy brown ceramic mug imbued with memories of Appalachia. Assorted photographs of human figures, transformed into white silhouettes that aren’t entirely opaque, sit atop a small table in see’s studio. The images echo Let no one say we were not here (2020-23), the artist’s installation for the Arizona Biennial 2023 (April 1–October 1, 2023) at the Tucson Museum of Art.

“This work is about grief,” she wrote in her statement posted with the piece. “It started as an attempt to visualize the death toll of COVID-19 after losing a member of my family.”

As noted in see’s statement, she’s employed white gouache to erase individual identities and create a shared family album of collective loss, inviting community members to participate by contributing their own images. But she’s also critiqued the construct of whiteness, the disproportionate impact of trauma on those who are systematically oppressed, and the ways oppressors control historical narratives.

Through the years, see has used performance, durational work, sculpture, fiber art, and other means to address racial, social, and economic injustice. She also folds community organizing, arts advocacy, and archival and curatorial processes into the mix.

For a 2021 exhibition at Revolve/Ramp Gallery in Asheville, North Carolina, they addressed concepts of home and housing injustice with elements including a sculptural steel frame of a house set on sod and two wall-mounted shelves displaying more than seventy paint samples for various shades of white. The artist also performed on-site topographical drawings of planned communities and shared information on various ways to find or give community support.

For more than two decades, photography has been a throughline of see’s creative vision. “I was a rock photographer in the early 2000s,” she says, referencing concerts rather than hiking trails. “I was kind of punk in high school, and I loved spending time in anarchist spaces.” Now, at age thirty-eight, she’s still questioning systems of oppression and elitism while also working to increase “community engagement, equitable access, and representation.”

In many ways, see’s work is rooted in their own personal history.

“I’ve been in motion my whole life,” they share, explaining that they lived in four states and frequently moved as a child. Recounting the anxiety they felt growing up with undiagnosed learning disabilities, see describes channeling their nervous energy into theater, dance, and other forms of cultural production. “I make art to belong to something; all of my art is about situating myself as a person with belonging.”

Lately, she’s been experimenting with ways to make woven baskets out of reed, cane, and salvaged plastic produce bags, thinking about how she can push the materials enough times to find what works. “I have a compulsion to collect things, but I let the materials dictate how I use them,” she explains. Noting that her learning style is based on process rather than outcome, see says she often learns through what her hands are doing. “I love slow work, even though capitalism doesn’t encourage it.”

The artist, originally from Massachusetts, earned their MFA at Western Carolina University in 2021. The next year, see became gallery director and curator for the UA School of Art. Moving to Arizona has meant getting to know a new landscape, which see often explores with her husband Eli Blasko, an artist and designer whose work is also part of Arizona Biennial 2023.

“We love the diversity of ecological life here, although leaving familiar flora and fauna in Appalachia felt like leaving old friends,” says see. “The desert is constantly telling you that we don’t belong here, and I respect her for that. I’m seeking permission from the beings around me to be part of things here.”

Inside the couple’s home, foraged and found objects spill beyond see’s studio into other spaces, where walls bear eclectic artworks tied to memories and shelves hold artifacts of connections with family, friends, and community. It’s unclear how see’s art practice will evolve moving forward, but the vibe of see’s studio suggests that people and place will continue to inform her creative journey.

“I try to be generous with myself and the process,” says see. “There’s no one right way to be a practicing artist.”