Dallas-based painter Jay Chung addresses climate change and challenges perceptions of the human figure.

Art, like nature, produces a feeling. What is the latest emotion you’ve felt? There’s a good chance you will find it in Jay Chung’s paintings, which are grounded in a form of humanitarianism that magnifies urgent issues of the day.

I was privileged to meet with Chung on a late afternoon in November 2021, the sun draining the last of its light through the glass doors. Nearly a dozen plants huddled in the center of his Tin District studio in Dallas. They felt as if they belonged there, like they grew from the concrete floor, an art in its natural state of being.

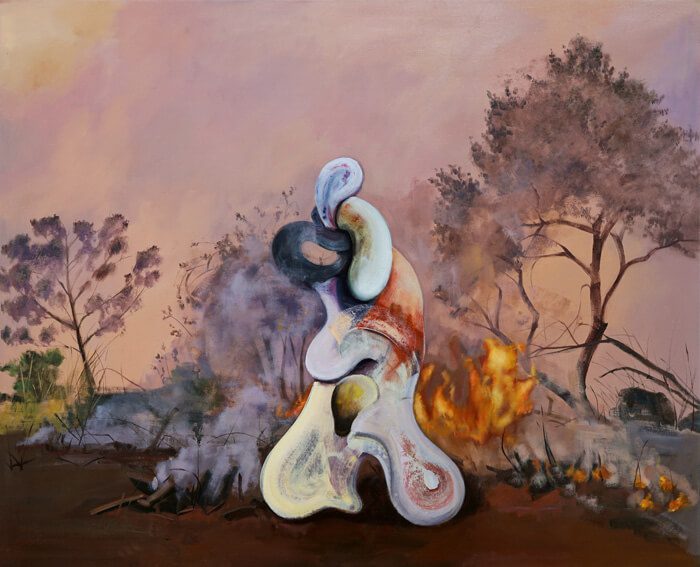

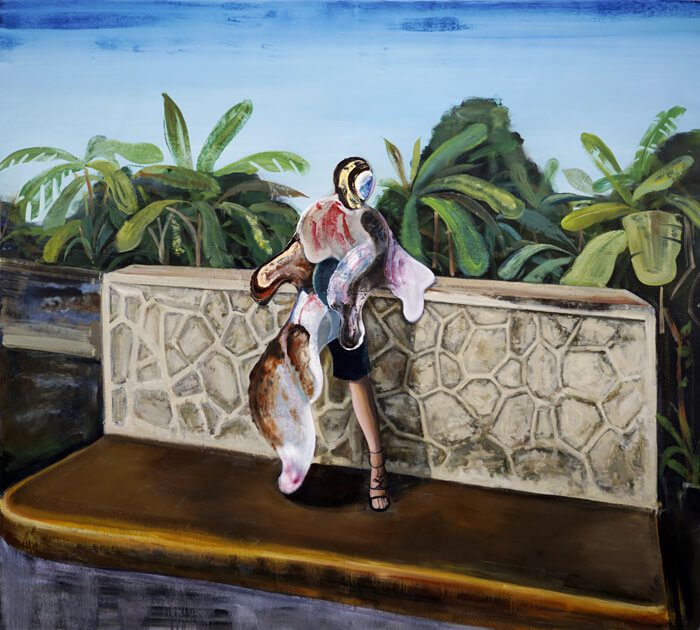

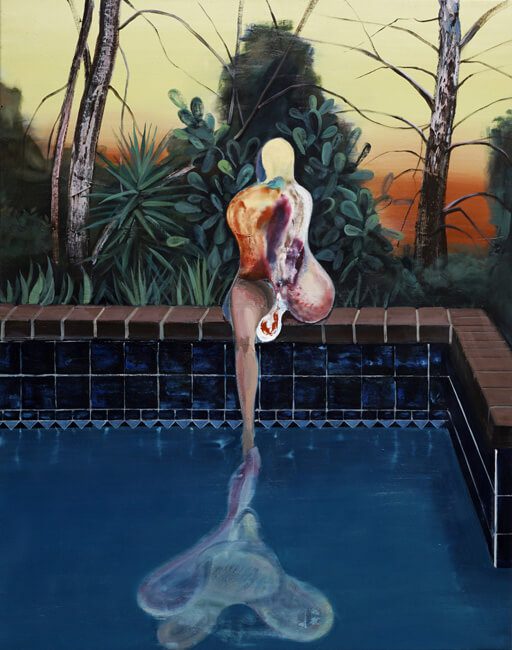

Natural is an arduous burden for the human figure, a task that Chung, a Korean artist who was recently named a Saatchi Rising Star, examines in his work by “eschewing conventional representation.” Oftentimes, his paintings present an alternative human figure which looks as if it has been regurgitated from the inside out, a testament to our conscious and unconscious experience of being in the world.

Chung, whose work was featured in this year’s The Other Art Fair, took a circuitous path to become a working artist. His previous career as an architect left him feeling discouraged, especially after participating in the company’s community service program on Native American reservations. “After three years of helping build schools and toilets, nothing changed,” he says.

He went on to study art therapy in Boston, but after finding it prescriptive, he decided to fully pursue art. “I didn’t plan to be an artist at all… it’s more like a destiny.”

His art has since become a social-based humanitarian practice—Chung has volunteered at several refugee camps in Bangladesh and Greece and an orphan camp in Ghana. “I try to think about the places I visit and my emotions about the situation.” His work, including his latest series of paintings that are in response to climate change, is in conversation with the human condition and the emotional state of the world. Earlier this year, Chung had planned to camp in California for a week, but the Dixie Fire destroyed his campsite.

The experience helped inspire the Code Red Series. The contorted figures in the series, posed in the middle of the frames in stressful and emergency forest fire situations, comment on how the planet is losing nature at an alarming rate. The work also portrays how our interior manifestations affect our exterior selves.

Chung’s explorations challenge the conventional idea of the human body—the shift between ambiguity and familiarity of the figures feel natural, honest, and vulnerable as if the human form should always be represented in this way.

“The human body is not saying everything. What I’m trying to do is bring out that potential,” says Chung, who adds, “The first time I painted these figures, it was really hard to make them out… but now I think it’s more naturally coming out of my imagination.”

Whenever I experience an artwork, I have a natural curiosity for how an artist transforms a blank slate into a finished painting. Chung stretches four or five canvases on the wall and then jumps back and forth between each work in progress. “It’s really a fast process, maximum two months,” he says.

Guided by instinct, he credits his bare hands as the most used brushes. His process is grounded in gesture with no sketching involved. “After I paint, I don’t remember how it happened,” he says. Once the paintings have been completed, he feels that “everything came out accidentally.”

At work in the studio, the artist is a naturally gifted painter who alerts the viewer to the unnatural state of the world while offering a different perception of ourselves. We are full of emotions and complexities, and Chung’s paintings are showing us who we potentially are from the inside out.