Curator Alana Wolf mines the University of Utah’s archives to backdrop the various occurrences of the 1970s—the formative decade in which Robert Smithson’s earthwork Spiral Jetty made its debut.

SALT LAKE CITY, UT—In the spring of 1970, Robert Smithson and his wife and fellow artist Nancy Holt solidified a special use lease with the Utah Division of State Lands for ten acres at the Great Salt Lake, setting in motion the creation of one of the 20th century’s most well-known artworks. Over the course of several days, Smithson, with the help of local contractors, carried more than 6,000 tons of stones to form a 1,500-foot-long configuration, the now-iconic Spiral Jetty.

Now, a new digital exhibition and online resource hosted by Salt Lake City’s Utah Museum of Fine Arts showcases historical information collected not from the Great Salt Lake, but from the human landscape surrounding Smithson’s earthwork and his subsequent visits to the University of Utah during a brief visiting professorship.

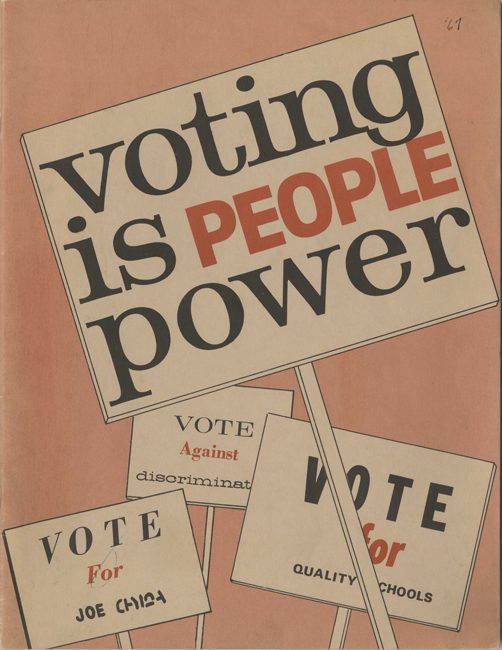

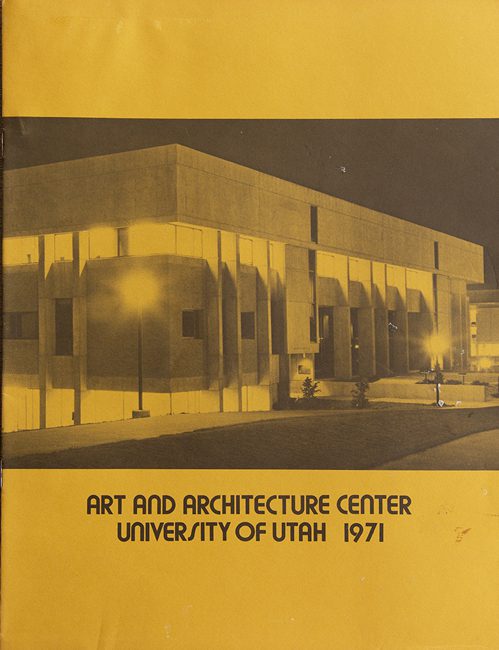

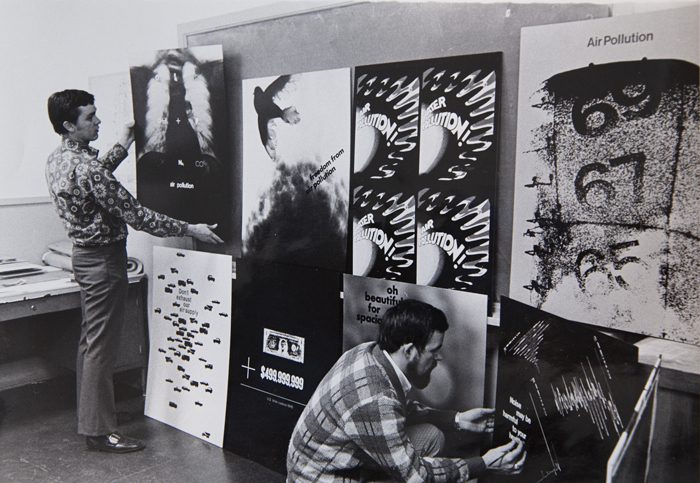

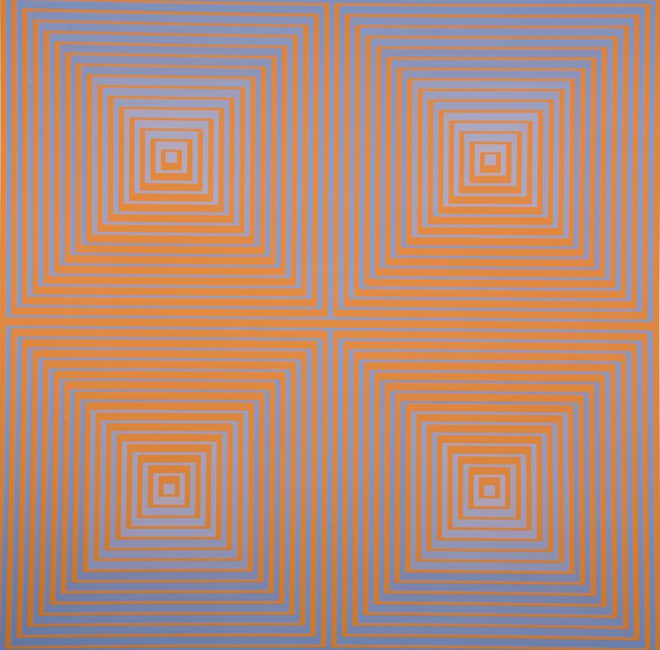

Time Trip: Utah, Spiral Jetty, and Robert Smithson in the 1970s is arranged thematically to take participants on a “trip” through the decade in which the seminal work was made. The exhibition’s conceptual curation allows participants to click on a specific theme to learn more about topics and events contemporaneous to the building of the Jetty, all Utah and often University of Utah-specific. Among them, the construction of the University of Utah’s art and architecture building and the UMFA, student protests against the Vietnam War, ecological research, as well as artistic and cultural movements in the 1970s.

In 2019, Alana Wolf began diving into archival materials at the University of Utah’s J. Willard Marriott Library, as well as those of the UMFA, the state’s flagship art museum located on the university’s campus. Wolf, who received her PhD in 2021 in visual and cultural studies from the University of Rochester in Upstate New York, served as the museum’s collections resource curator until April 2022. She began her tenure at UMFA in 2018 after the U of U was awarded a significant grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to reconcile the library and museum collections.

At various points throughout the process, Wolf was amazed at what she found—several examples of student protests, progressive groups on campus, and a spirit of activism and civic engagement during an episode of tremendous political upheaval.

Among her incredible finds were various interdisciplinary collaborations—between dance and computer science as well as art by Ronald Resch, professor of electrical engineering, and Richard Taylor, a pioneer of multi-media immersive presentations. She also discovered the numerous contributions of student groups on campus, including the Associated Students of the University of Utah’s involvement in art acquisition for the UMFA, a range of critical and countercultural speakers, and a freshman orientation video skeptical of the higher education system at large.

Notably, it’s the university, not Smithson, that is the star of this showcase. In this respect, the project feels like an institutional investment for one of the state’s longstanding harbingers of academic and social thought.

Still, Smithson, an artist whose unique vision of the once-radical Land Art movement set in motion decades of interest, scholarship, and admiration, has become an indelible fixture of UMFA’s programming over the past several years.

The work of the museum and scholars such as Hikmet Sidney Loe, whose The Spiral Jetty Encyclo (2017) is perhaps the most comprehensive resource on the artwork to date, have done much to spread interest and knowledge of Smithson’s world-famous earthwork to regular Utahns. (Loe is a Southwest Contemporary contributor.)

Yet, as the fiftieth anniversary of the Jetty’s creation loomed, Wolf was tasked with creating an exhibition cognizant of the work’s significance in the state.

“I was mindful of the fact that having a traditional anniversary of the Spiral Jetty was contrary to Smithson’s notion of non-linear time,” Wolf tells me.

Indeed, Smithson often cited his fascination with entropy—the geological change in an underlying system over time—as a conceptual underpinning of Jetty. The knowledge that the work would evolve and become something new for a wide range of visitors was part of the point.

Wolf draws a parallel here with her research, which was originally designed to debut as a physical exhibition but evolved to its digital format due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There is something really incredible about seeing the original archival materials displayed and viewing student protest videos in the way they were intended to be seen,” she says, relaying a sense of disappointment in the inability to execute the original concept.

She admits that the new format feels less like an exhibition and more like a digital resource. In this regard, she hopes it will spawn further inspiration for art historians wishing to dig into the incredibly rich activity on the University of Utah’s campus during the 1970s.

“Perhaps the most compelling prospect for Time Trip‘s transformation into a digital exhibition is that it can—and ideally will—evolve over time. It is understood that new material may be added—new narratives may emerge,” Wolf relays in the exhibition’s press release.

Wolf’s project embodies a new direction in the ever-expanding discipline of art history and visual studies in line with the digital humanities movement, which emphasizes the intersection between scholarship and technology. While hers is undoubtedly a historian’s endeavor, she believes unlocking the historical circumstances under which art is made—what she refers to as the human landscape—is a vital and fulfilling endeavor.

Readers can access Time Trip: Utah, Spiral Jetty, and Robert Smithson in the 1970s by visiting the UMFA’s website.