The two-person show Wicked Wells and Window Wipeouts traps the viewer between a hard place and a sunken one—but its ambiguity offers a different kind of freedom.

Wicked Wells and Window Wipeouts

December 6, 2024–January 19, 2025

Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art, Roswell

Wicked Wells and Window Wipeouts, the title of the current two-person exhibition by Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program participants Tristram Lansdowne and Ryan Crowley at the Anderson Contemporary Museum of Art, is elusive and adeptly descriptive. Like the artwork on view, the title functions on a peripheral understanding that quickly warrants a double take.

I’m not entirely sure what constitutes a wicked well, but I’m almost certain a window wipeout is when our avian friends fly headfirst into glass due to an inability to decipher reflection from reality. This comes to mind when viewing paintings by Lansdowne, whose technical mastery of watercolor mirrors such trickery. For decency’s sake, it feels important to mention that not all critters die from this phenomenon; some are simply stunned by the impact. Still, though, they fall to the ground, laying motionless and vulnerable, having smudged up your glass in the process.

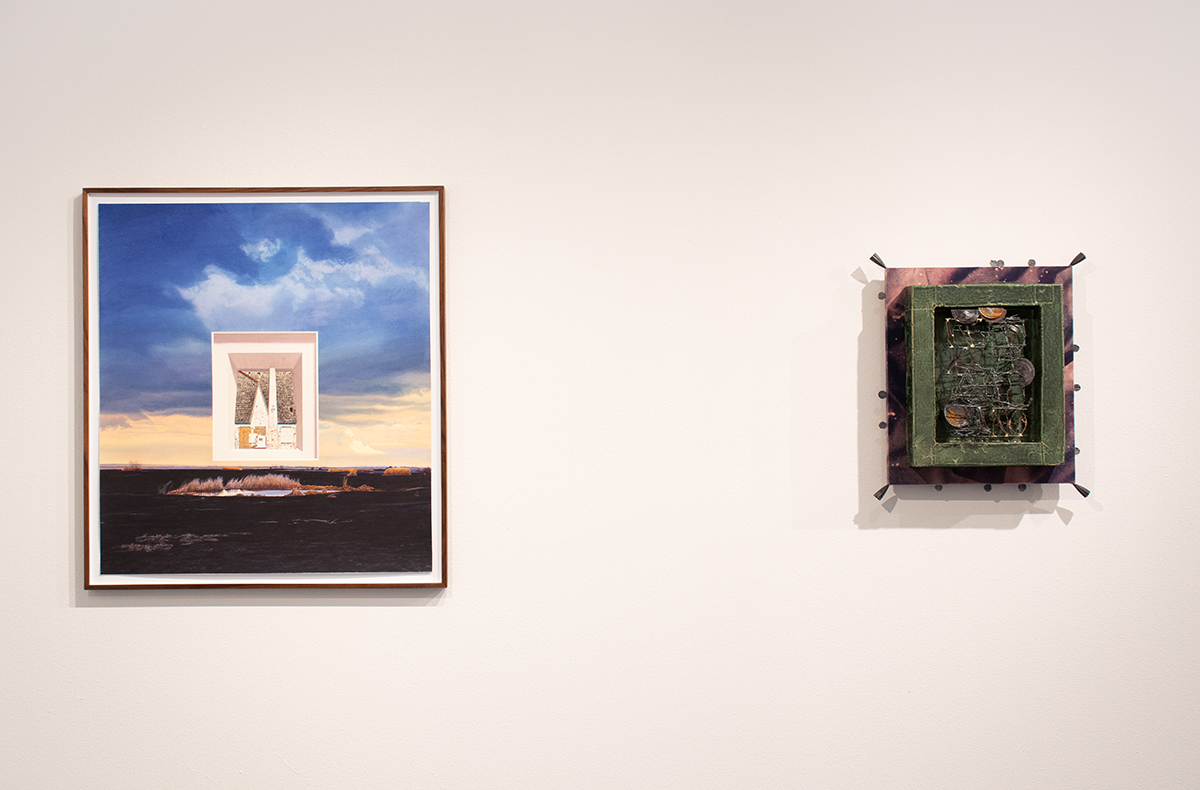

Speaking of smudges, Lansdowne’s technical capacity to render photorealism is the least interesting aspect of his painting. While his finesse in watercolor is undeniably impressive, his engagement with the subject of space and dimensionality is much more demanding. Each painting on view comprises one or more framing devices: pictures within pictures, archways, cubbies, and warped landscapes.

(In Lansdowne’s paintings) value and ownership are distorted by the relentless churn of consumption and waste.

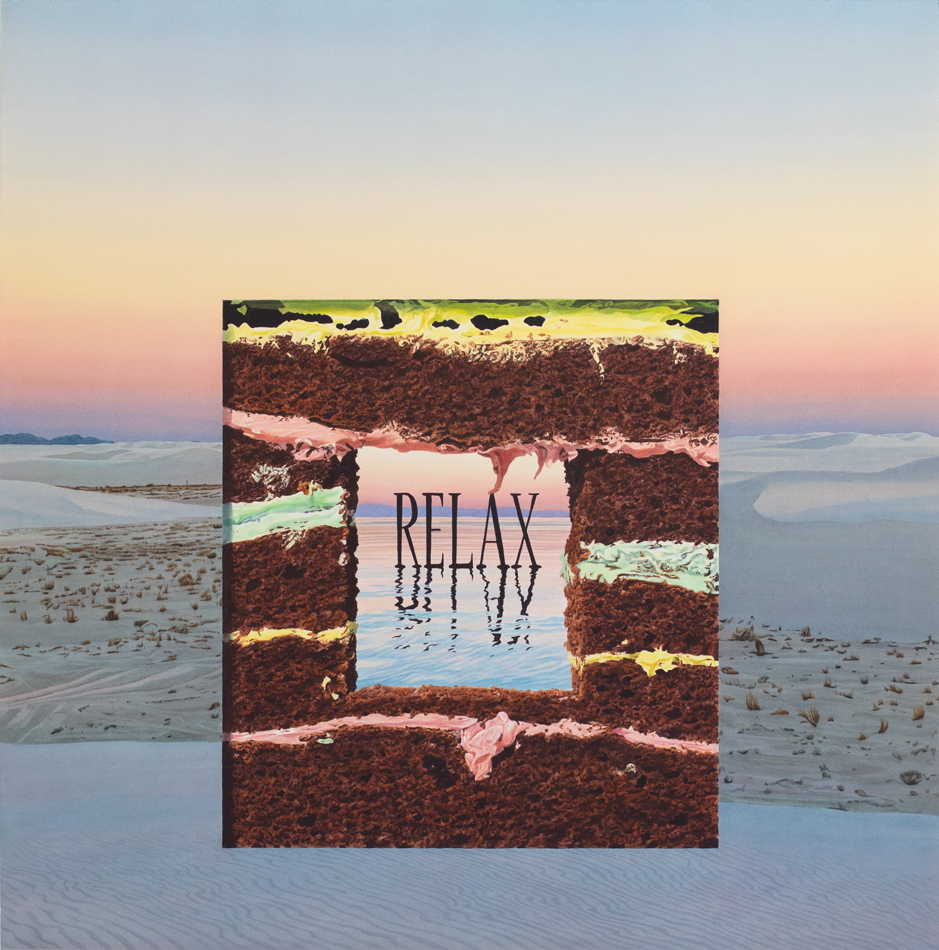

Cue Imperative (2024), wherein a dusk-illuminated White Sands frames a frosted, chocolate layer cake that windows an opening to another landscape centering serif text resting atop a reflecting pool reading “RELAX.” This process of stepping inward and outward and layering of varying genres suggests an engagement with the history of painting. As a main accomplice to Western ideas of perspective and value, painting has a historical stranglehold on our understanding and perception of things. John Berger famously attributed the consequences of this conditioning specifically to oil painting, detailing how its unique material capacity to render pictorial representation combined with early European models of patronage created an elite, circular economy of ownership and possession. Instead of a “window into the world,” Berger declared, traditional painting would be better regarded as a personal safe.

Lansdowne’s trompe l’oeil expresses a critical awareness of the historical legacies and traditions that condition culture as well as genre paintings’ susceptibility to market recuperation. Moldy sponges, slugs, everyday consumer trash, and dilapidated houses are featured prominently throughout the various works. His medium of choice, watercolor on paper, offers an inherently matte surface (as opposed to the sheen of oil painting and acrylic varnish). This material quality is significant to the success of his particular approach as it contrasts directly with our screen-dominant culture and the glossed images of print-based advertising that linger. Less an imaginary window or mirror, Lansdowne’s paintings function more like showcases displaying the detritus of excess and disparity, where value and ownership are distorted by the relentless churn of consumption and waste.

While Lansdowne’s paintings seem to taunt their own objecthood, Crowley’s sculptures have a flirtatious relationship with the pictorial plane. Uniquely, only two out of the nine sculptures included in the exhibition touch the ground, with the rest mounted to the wall. The freestanding works, however, also appear to suggest specific viewing orientations. Take Swizzle (2024), which resembles a handmade sidewalk sign or a small appliance. The “front” of this object is suggested by the formal arrangement of the objects affixed to it, namely handwritten text reading “STAY ALERT,” a pair of wonky, plaster-cast eyes, and another text-based drawing that appears to be less about legibility than the presentation of the text itself. The “back,” consisting of the exposed rebar frame along with a hodgepodge of objects and materials such as half of the inside of a coconut shell, magnetized balls, and additional text-based imagery, feels at once rewarding and a bit nosey, like accidentally peeping a glance at someone’s junk drawer or the exposed wires behind a flatscreen TV.

Crowley’s awareness and attention to the privileging of objects’ front-facing orientation is a clever way to critically engage with one of sculpture’s primary formal concerns of encouraging orbital movement. It also illuminates the sociocultural tendency to present things, including ourselves, with specific and limited directionality. This contradictory tension between an object’s front-facing representation and its wholeness mirrors the orientation inherent to the physicality of conversation.

While it would be reductive to simply anthropomorphize Crowley’s work, the metaphor brilliantly threads through his practice.

The wall-mounted XEX Epiglottis (2024) further implies an object’s capacity (or lack thereof) for address. Incorporating a densely stacked list of materials, including plaster, ash, magnets, ceramic, and much more, the object resembles some kind of satellite, antenna, or kite. An epiglottis, the flap of cartilage in the back of your throat that blocks food or liquid from entering the lungs when swallowing, ensures that things go down the right pipes. While it would be reductive to simply anthropomorphize Crowley’s work, the metaphor brilliantly threads through his practice, with the recurring subject being signaling, communication, or an object’s capacity to channel meaning.

Material transformations and associations in Crowley’s sculpture feel intentionally obscure. They seem to, at the very least, resist simple description. There is a similar obfuscation in Lansdowne’s painting, where successive beveling and vignetting create a sense of disorder. Admittedly, this makes their works challenging to read—even more so considering both artists’ material density and attention to detail. Although, perhaps this is what makes a well wicked: the consequences of gazing into the unknown, and all the fear and excitement that the act of looking entails. At a time when so many institutionally supported artists seem all too eager to declare ideological positions and when so much artistic production leaves little room for interpretation, Wicked Wells and Window Wipeouts feels like a refreshing reminder of the possibilities occasioned by playfully refusing coherence. We only have to consider it more productive to crash into a window rather than remain stuck staring at a mirror.