Sister SLC’s creative, fun, and diverse one-off events are as a safe space for all genders, sexualities, and ethnicities, and increase visibility for Utah’s femme, queer, and nonbinary artists.

SALT LAKE CITY, UT—Many museums, collectives, and publications that center their objectives around local artists—specifically, marginalized artists—often have the same mission in common: creating safe spaces and critical discussion through art. While these institutions offer essential, thoughtful, and progressive platforms for marginalized artists’ work, the artists themselves can still feel a disconnect from the space and intention of the curator—like less of a featured artist and more of a feature themselves. And as these artists take space within the predominantly white, cis-het artist landscape of Salt Lake City, Utah, does the space ever feel like their own?

Sister SLC is inspired by the concept of creating platforms and safe spaces built by a community of their own peers. It’s a project aimed to increase visibility for Utah’s women, femme, queer, nonbinary, and gender non-conforming artists and creatives through interdisciplinary lineups.

“What we are trying to do [with Sister] is to revert the formula of white, cis-het, male lineups with diverse one-offs,” says Maru Quevedo (she/they), who created Sister SLC with Jordan Danielle (they/he). Sister subverts Salt Lake’s tendencies by creating spaces for underrepresented artists, offering true, big-picture equity, pruning the cisnormative perspective in a city where it is overgrown.

Rather than perceiving Sister as a disruption to an already progressing and burgeoning art scene, Maru and Jordan see their project as an enhancement.

“[Sister is part of] the direction of where Salt Lake City is going in congruence with the growth in language, perspective, and inclusiveness that the city is ready for and needing to have in this moment,” Jordan says. Sister is attempting to apply the ideologies that other, more diverse, cities have already implemented. “Institutionally, our scene is lacking representation… especially those communities of color, but they have been here—they have always been here,” Maru says.

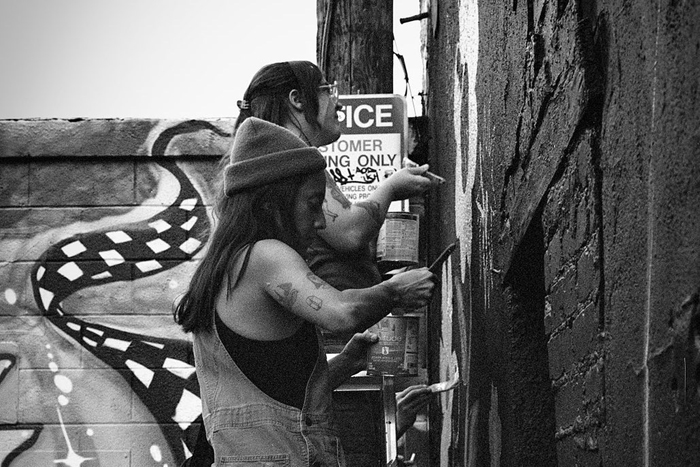

Sister’s first event took place on March 8, 2022 with the intention to celebrate International Women’s Day. Hosted at Medium Studio in Sugar House, a Salt Lake City suburb, the walls were lined with work from femme, female-identifying, and non-binary artists such as Chloe Monson, Clover Mills, Lunares, and Irlanda Trujillo.

The work ranged from digital art, analog photography, collages, and even acrylic on skateboard. Poet Jai Hamid Bashir set the intention and tone by performing a piece about womanhood in Palestine. “You can tell it was something the community was so excited to come out and support,” says participating artist Lunares. “Everyone came to show love and validate each artist through their patronage.”

Maru and Jordan are working for the artists existing within intersectional identities that, depending on the whims of some curators, may or may not be offered a spotlight—save for the annual Black History Month features or “curated” exhibitions of “BIPOC artists” as perceived by a white lens of curation in a predominantly white gallery. Simply put, these opportunities do not offer these artists consistency or longevity within the fine arts scene, instead creating a bubble of conditional, immaterial support, leading to an unsustainable ecosystem for artists. These initiatives are better understood as performative “diversity and inclusivity” insurance, where curators can claim to be “doing the work” rather than acting as legitimate pipelines to putting resources into marginalized hands. This is where Sister’s direct approach comes in.

Part of Sister’s mission is to offer participants accessibility to resources in addition to visibility, an objective that comes from a deeper understanding of what artists need outside of a pedestal under a spotlight.

“There have been several spaces that have been trying to push diversity. I just think we need to think of the specific challenges of those communities,” Maru says. “People of color usually don’t have access to print large scale or to frame in a nice way. It is tricky to invite them without providing those resources.”

Sister, through their event fundraising, is able to offer funds to invited artists for any materials they might need like canvases, framing, printing, and enlargements. Most recently, Sister has been able to collect enough money to pay participating artists for their attendance.

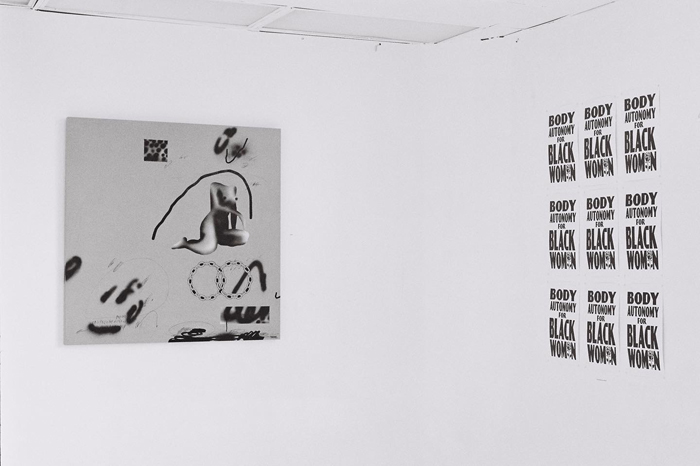

Other fundraising and educational methods include prints and zines they create in-house. Sister put together a zine for the Black Birth Workers Collective, a collective Jordan is part of as a birth and postpartum doula, that talks about the importance of birth and postpartum care for Black people with uteruses and the history around the medical negligence that has disproportionately taken the lives of Black people. “All the funding that we get from that goes straight back to the artists and the cause,” Jordan says.

Today, Sister stands with three successful events under their belt: the International Women’s Day exhibition, the Sister Fice Gallery Show (with the support of Planned Parenthood of Utah, Project Rainbow Utah, and the Utah LGBTQ+ Chamber of Commerce), and the Pride Pop-Up Gallery (in collaboration with Social+Antidote and Open Streets).

“Being part of Sister felt so familiar and organic,” says Mao Barrotean, the featured visual artist for the Sister Pride event. “As a brown queer dude, I felt so grateful for having the opportunity to put my work out there in such a bold and vulnerable way.”

Sister looks forward to an upcoming in-the-works Hispanic Heritage Month event with Social+Antidote alongside a string of exciting events soon to be announced. You can keep up with Sister on Instagram, or reach out via email to hello.sister.slc@gmail.com to inquire how you can support their mission.