As Colorado- and Maine-based artist Anna Tsouhlarakis presents an elaborate Northeastern rendition of The Native Guide Project, she looks back on the Southwestern roots of her artistic practice.

Transdisciplinary artist Anna Tsouhlarakis (Navajo/Creek/Greek) has never aspired to perfection. “Ideas about refinement, beauty, precision—I always wondered why is that what we have to attain [as artists],” she shares with me from her home in Maine (she lives and works between Maine and Colorado). The artist works across various media, often incorporating materials that are not as she says, “necessarily expected or kind of thought of as materials that Native artists use.” This is clearly getting her noticed: Tsouhlarakis’s work has been on heavy rotation at museums and art spaces in recent years, with a recent solo exhibition at MCA Denver in 2023 and a current land activation commissioned by Indigo Arts Alliance at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens.

The daughter and granddaughter of Navajo jewelry makers and silversmiths, Tsouhlarakis grew up around art and craft. “I come from a long line of artists and I was always making things when I was younger,” she says. “I did not ever think of myself as an artist necessarily—it’s just what we did.” The artist grew up learning beading, moccasin-making, and pottery—but never saw that as the career she would pursue. “It really wasn’t until college where I realized that [art] was something that interested me and I wanted to pursue.”

During her studies at Dartmouth College, where she received her BA in Native American Studies and Studio Art, and then at Yale University where she earned her MFA in sculpture, Tsouhlarakis was exposed to a broader spectrum of what art could be and how it could be a powerful tool for social and political change. “I realized there were more ways of working when we learned about art history; Latin American art, African American art, and how people working within performance and video and all of these different mediums in the late 90s,” she shared. “There were Native artists working in this way too, but I wouldn’t say it was plentiful [at that time].” One artist who was a major influence on Tsouhlarakis was David Hammons. “The way that he used material to speak to his experiences, to the contemporary Black experience, that really resonated with me. I felt that was a language I could easily understand even though it was brand new to me. That’s what really pushed me to start making work that way.”

I was very aware of the fact that I’m not Wabanaki, that I am not traditionally from this land. So what did that mean?

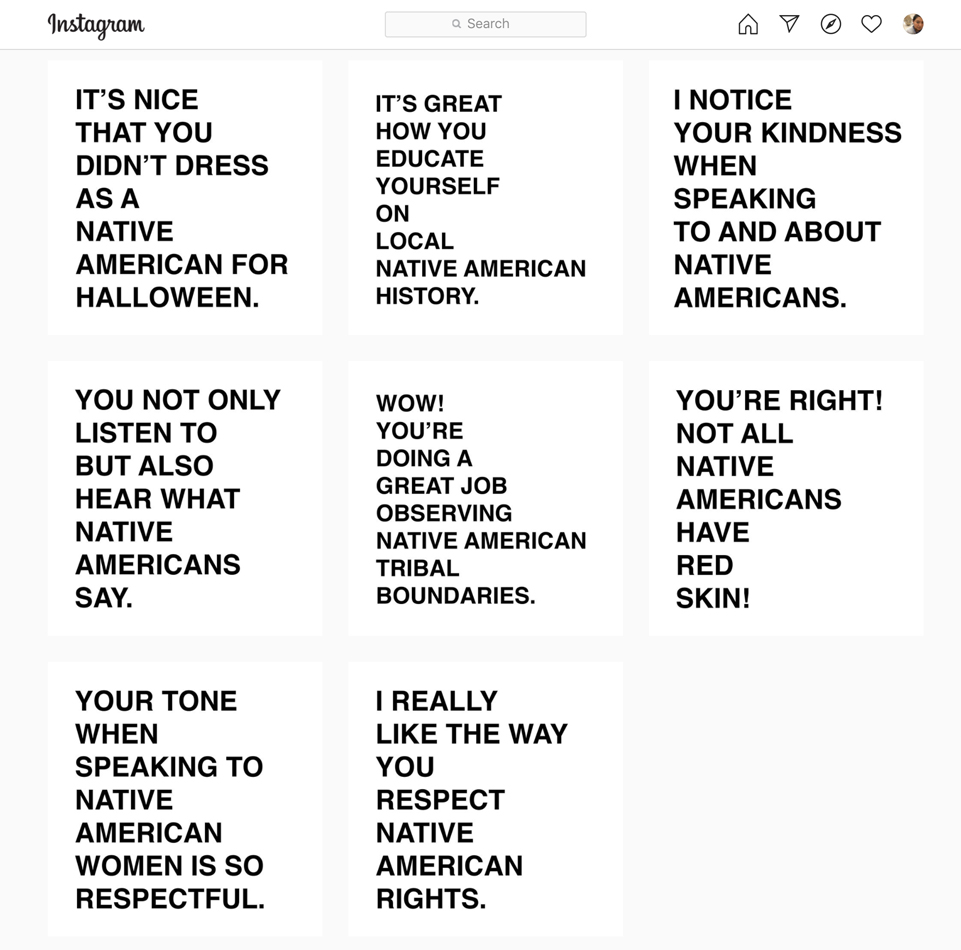

Tsouhlarakis’s inquiry-based practice has frequently manifested in sculpture, installation, and film. As of late, she has heavily included text as medium—even merging her sculptural works with text—as seen in her ongoing series The Native Guide Project. The series manifests as billboards, bus shelter banners, and other outdoor public signs, which contain phrases like “I REALLY LIKE THE WAY YOU RESPECT NATIVE AMERICAN RIGHTS.” and “IT MAY BE CALLED COLUMBUS BUT IT’S STILL NATIVE LAND.” These graphic black-and-white works create a sort of intervention in communities where they are placed—confronting viewers with statements that implicate their existence on Indigenous land and illuminate the lived realities of Native peoples. The project has traveled to Scottsdale, Arizona, St. Louis, Missouri, and Columbus, Ohio.

Born out of the artist’s need to create digital community and fellowship with other Indigenous artists, Tsouhlarakis began sending Survey Monkey questionnaires to colleagues in the field—gathering and synthesizing their responses into the Native Guide works. “These words have a directness, I realized like I don’t need to have work that’s esoteric—that you have to dig through it to find the meaning,” she said. “I was thinking of using text in a lot of different ways and I realized, ‘Why am I trying to fill it up with some lace and glitter or something?’ It’s good the way it is and it’s true the way it is.”

For her work at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, that merger of sculpture and text is fully realized. “I came out for a site visit in November of last year and started thinking about what I wanted to create,” the artist shared. “I was very aware of the fact that I’m not Wabanaki, that I am not traditionally from this land. So what did that mean? What is my like relationship with this land and how do I form that without trying to overtake the Indigenous voices that are here?” Tsouhlarakis recalled visiting the Damariscotta Middens with her father-in-law several years prior, which is in close proximity to the Gardens. “It’s a place where there are these heaps of oyster shells by the river. I just imagine that Natives that lived here five, ten thousand years ago found these oysters [and] were eating them and just started throwing them over their shoulders and it built up the middens, which are over fifteen feet tall.”

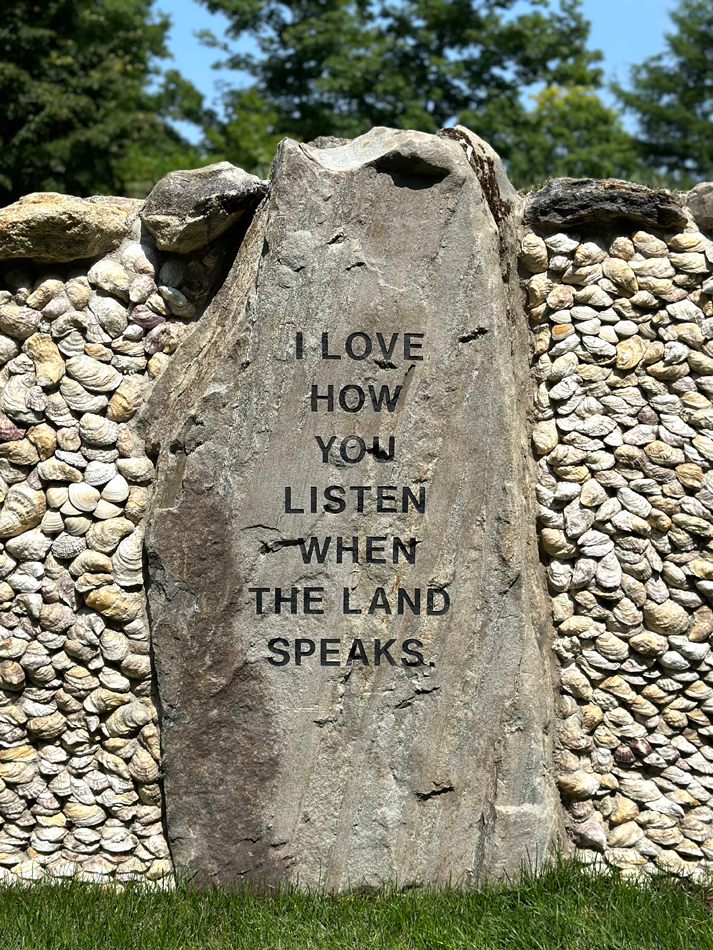

These earth mound-like middens were excavated in the 1800s and served as inspiration for the earth sculptures Tsouhlarakis constructed for the project. The Native Guide Project: CMBG (2024) recreates the stacks of oyster shells, grown over with grasses, with the inclusion of carved stone fascias that read “YOU’RE RIGHT, THIS IS NATIVE LAND.” and “I LOVE HOW YOU LISTEN WHEN THE LAND SPEAKS.” The work looks at the continuum of Indigenous existence, creativity, lifeways, and connoisseurship and amplifies the reality that Native people are the original caretakers and storytellers of this land.