It’s reseeding day at Chispas Farms, and I’m planting provider beans in the empty row between the tomatoes and the chard. I push the dry beans in as deep as my first knuckle, close to the emitters on the drip tape to ensure they get as much direct water as possible. This is how Casey Holland, the steward of the farm, has told me to do it. She also told me to lick the bigger seeds before I plant them—to give them a head start and establish a connection—to let them know who’s going to care for them. After I finish planting, I look down at the row and whisper, “Safe journey.” It just feels like the right thing to say. These seeds have an uphill battle to fight.

In 1999, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization issued the frightening results of its study on agrobiodiversity. “Since the 1900s, some seventy-five percent of plant genetic diversity has been lost as farmers worldwide have left their multiple local varieties and landraces for genetically uniform, high-yielding varieties,” the report states. That was twenty years ago now, and the trend has not altered.

Most commercial farmers are now growing vast quantities of one crop—typically a patented, genetically modified plant variety created by a large corporation such as Bayer-Monsanto—instead of a wide variety of “landrace” crops that have been adapted to their geographic region over generations. This practice of monocropping strips communities of the traditional foods and agricultural knowledge that has sustained them for generations.

Genetic diversity is important in plants for the same reason it’s important in humans and animals: a shallower gene pool means more vulnerability to disease and mutation and less adaptability to environmental change. Throughout human history, farmers have benefitted from plants’ ability to evolve over time by carefully selecting seeds from their harvest to plant for next year based on drought tolerance, disease resistance, productivity, or other desirable traits. This long partnership between growers and seeds has created countless unique plant phenotypes, many of which are now extinct or going that way.

Throughout human history, farmers have benefitted from plants’ ability to evolve over time by carefully selecting seeds from their harvest to plant for next year based on drought tolerance, disease resistance, productivity, or other desirable traits. This long partnership between growers and seeds has created countless unique plant phenotypes, many of which are now extinct or going that way.

To fight the tide of species die-out, seed banks have sprung up across the globe to house vast numbers and varieties of seeds. You might have heard of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, the famously brutal-looking building nestled in the icy, unforgiving Arctic tundra that is supposed to be humanity’s last-ditch effort at preserving agriculture in the case of large-scale ecological collapse. Ironically, this stronghold is itself falling prey to climate change: the permafrost around it is beginning to melt. Although the cold and the low humidity make the Arctic an ideal site for preserving seed viability, the temperatures there have been rising more rapidly over the last several years than anyone predicted. If the vault floods with meltwater, it could destroy seeds that otherwise are meant to remain viable for thousands of years.

Thankfully, many growers know that relying on a universal silver bullet solution for the agricultural end times isn’t practical—which is one reason why the practice of seed saving has again been catching on among small-scale farmers. Preserving a diversity of seeds in a variety of places is the best way to ensure that at least some of them will weather the proverbial storm. And the best way to save a seed is to grow it—and grow it widely.

“I don’t really agree with the idea of seed banks,” says Jeanette Hart-Mann, one of the founders of the storytelling collective SeedBroadcast. I’m speaking with her outside the Albuquerque Museum at the opening event for the exhibition SEED: Climate Change and Resilience (June 22-September 22, 2019), the culmination of several years of work from many people throughout the American Southwest and Central America. The exhibition features stories about seeds in writing, recorded audio, and photos contributed by local farmers and gardeners. A special issue of the SeedBroadcast’s “agri-Culture” journal of the same name also accompanies the show. This free, biannual publication is available at the Museum and can usually be picked up at the Downtown Growers’ Market as well.

SeedBroadcast is, in many ways, the opposite of a seed bank—it says so right in the name. Resources held in many hands are always more reliable and accessible than resources held in the hands of a few.

“All our creative/performative actions are inspired by the open-source movement—spreading open-pollinated seeds, resources, and stories and acting as pollinators ourselves by encouraging others to take it and run with it,” says Hart-Mann in one of the essays in the special issue of SeedBroadcast. Open-source, which was a term originally applied to software whose creators shared its source code for free online to encourage further creation, applies well here, because similar intellectual property law now protects corporate lab-developed seed varieties. It is illegal to save seeds from plants grown with these patented seeds, as those resulting seeds could be genetically different from their parents—an adaptation of the original work.

Resources held in many hands are always more reliable and accessible than resources held in the hands of a few.

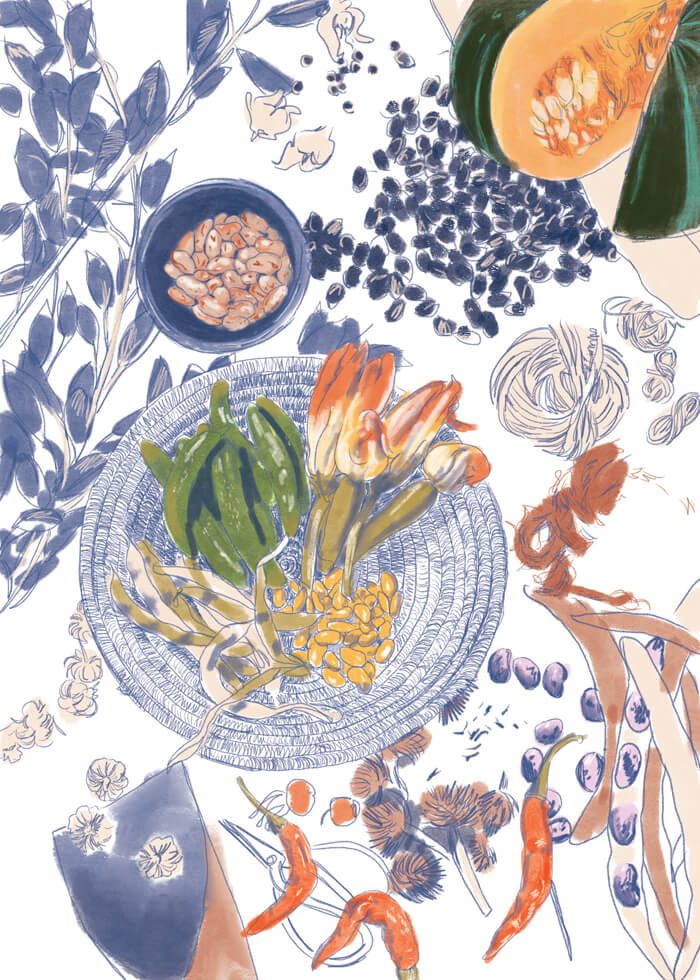

In New Mexico, preserving landrace seeds has become a passion project for many farming and Pueblo communities. Some of the heirloom crops still grown in this state have their origins in Pueblo farms from hundreds of years ago, and, to many people of that heritage, losing seeds is symptomatic of a larger cultural loss. Hopi Purple beans and Zuni Gold corn are not only symbolic cultural artifacts of the Pueblos, they are a means of regaining their food sovereignty from the systems of corporate agriculture that are unhealthy for them and their soil, air, and water.

Earlier this year, I went to visit the Tesuque Farm and Seed Bank in Tesuque Pueblo. There I met Emigdio Ballon, the steward of the farm and an expert in plant genetics. Ballon moved there from his home of Bolivia in 2005 to help the Pueblo revitalize its farm for future generations and grow food for local consumers. Ever since then, Tesuque Farm has been saving its seeds—first in the back of a box truck parked by the fields, and then in permanent adobe housing Ballon and his crew built in 2011. Down in the basement (which was painstakingly dug out of the clay-filled soil), hundreds of jars of seeds line the walls—speckled beans and multicolored corn, wrinkled peas, and tiny dark onion and radish seeds. There is wealth here that cannot be measured, and it is freely shared with anyone who asks. “Seed work is therapy,” Ballon says.

And he is just one in the long list of people who are preserving and sharing seeds in New Mexico. Tiana Baca, the Garden and Sustainability Director at the Desert Oasis Teaching Gardens in Albuquerque, has started her own collection of seeds specially adapted to growing in the Middle Rio Grande Valley. Baca calls this small but growing collection the Tierra Luna Seed Collaborative, and it’s her way of ensuring that farmers in the Middle Rio Grande Valley have a reliable source of seed for the rapidly changing Southwestern climate. “I want to know how we can do this for the community and not commodify it,” she says of the collection, which currently lives in the basement of Albuquerque Academy. She sees this growing into a larger collaborative effort of farmers helping one another—both through collection of seeds and a mutually shared compendium of knowledge on how to grow, process, and eat them. Some corn varieties are better eaten whole, and some make better tortillas, for instance. She wants to know which are which.

It’s not just farmers who are collecting and sharing seeds: public libraries throughout the state have started seed lending programs, too. To borrow seeds from the Albuquerque Public Library, all you need is a library card. You can have seeds sent to any of eight different library branches across the city, just the same as an inter-library loan with books in the system. Any individual can take out up to thirty seed packets per year, and there’s no requirement to bring back seeds saved for the next season. “Originally we were having people bring back seeds, but properly vetting the seeds became too complicated,” says Nancy Griffiths, the head librarian and curator of the seed library. She’s been an avid gardener herself for the past twenty years, and I can hear the excitement in her voice when she talks about the project. All of the seeds in the library are varieties particularly suited to growing in the arid Southwest, and some of them have even been sourced from local gardeners, like the heirloom amaranth variety called Elena’s Rojo. “We could always use more volunteer seed packers. Make sure to include that in your story,” Griffiths tells me.

It was Brita Sauer who started the Albuquerque Public Library’s seed lending program in 2014, when she was working as a librarian at the Juan Tabo branch. She was inspired by similar programs at other public libraries, especially the Pima County Public Library in Arizona, which helped organize the first International Seed Library Forum in Tucson in 2015.

“There’s a sense of urgency now,” Sauer says of the growing movement. “We’ve seen over the last hundred years the bottleneck where we’ve lost all these seed varieties due to a larger corporate agricultural model. I think that people are realizing that we could lose a lot more.” In 2018, Sauer took a job in the Santa Fe Public Library system and immediately set to work establishing a seed library there as well. The lending program launched this March, and anybody with a Santa Fe Public Library card can take seeds out at the Southside branch.

The small town of Estancia, just east of the Manzano Mountains, has its fair share of seed stewards as well. In 2012, Flordemayo, a curandera espiritu from Nicaragua, began work on a “Seed Temple” just outside the town, led by a vision she received from the Sacred Mother. She and a team of volunteers built this temple to “collect, protect, and share food, medicinal, and flower plant seeds” from New Mexico and around the world, with the goal of sustaining a healthy global food supply.

Greg Schoen, who lives outside Silver City, helped Flordemayo build her collection by gathering seed donations from all over, growing out the seeds they needed to increase in numbers, as well as scouting for new varieties. “Heritage seeds are vanishing,” Schoen says, “We’re rescuing a lot of stuff that’s on the edge of extinction.” Both Flordemayo and the library count on regional growers to propagate and return seeds to expand their holdings.

Growing one’s own food typically carries signals of independence and individual strength, but the seed savers point to a future where interdependence makes our communities truly strong.

This point was driven home as I stood outside the Albuquerque Museum for the opening event of the SEED exhibition. There, on the northern side of the building, Tiana Baca and a group of volunteers had created a garden to grow some of the seeds that stewards across the state had been saving. Everyone lined up to take a handful of glass gem corn or tepary beans from the farmers who grew them, then plant them in a checkerboard pattern in the waffle garden, an arid-land farming technique native to Zuni Pueblo. There were students from the UNM Art and Ecology program present, along with farmers, gardeners, organizers from environmental groups and Pueblos, as well as interested community members or passersby. All of us took a knee in the dry dirt, side by side, digging small holes with our fingers and planting the seeds deep, as instructed, then passing buckets of water back and forth to spill a little on our small squares of earth.

I felt that I was participating in a ritual as old as time: gathering with my community to sow seeds, in order to feed our families and ensure our survival for another winter. We will gather again in the fall to harvest, sharing the work and the bounty. And we will save the strongest, tastiest seeds to plant again, together, the next spring.