Artists Stephanie Leitch, Angela Ellsworth, and Nancy Rivera use materially obsessive processes to reflect on the mythos of Utah—a place shaped by the dominance of the LDS Church.

Utah’s mythos is indelibly marked by both its natural splendors and a cultural fixation with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“Mormonism as an influence for me is a backbone structure—[a] skeleton,” says Stephanie Leitch, an artist whose work is coded with influence from her Utah upbringing. She describes the religion in terms of “constraints” and “substrates,” but also as a source of creative imagination.

“It also imprinted me with a highly structured but at the same time mystical cosmos.”

A fundamentally American faith, the LDS Church garners associations with individual liberty and freedom from religious persecution. The urban design and public monuments from the early days of Salt Lake City cement these associations in visual form. Yet, various artists have challenged the perpetuation of this cultural monolith. Indeed, there exists a certain compulsive desire among Utah artists to define themselves either within or apart from this paradigm. This artistic investigation into Utah identity politics is, in many respects, obsessive.

These artists utilize painstaking, materially obsessive processes, to evidence the weight of Mormon culture on notions of gender, history, and countercultural identity.

Spells

“I was in the act of ‘spelling’ before realizing my full intent and implications,” says Stephanie Leitch. In both two- and three-dimensional form, the artist utilizes a meticulous process to map out what she calls “spells,” thousands of individual marks and materials that coalesce to form hypnotic works of art.

“The name ’spell’ is wordplay as I was simply spelling out words in a specific pattern,” Leitch says. “Assigning this same intention to my large-scale installations was a way of acknowledging what was happening on the micro scale within the macro, incorporating my actions in the making of the work and the act of completion in the viewer’s experience.”

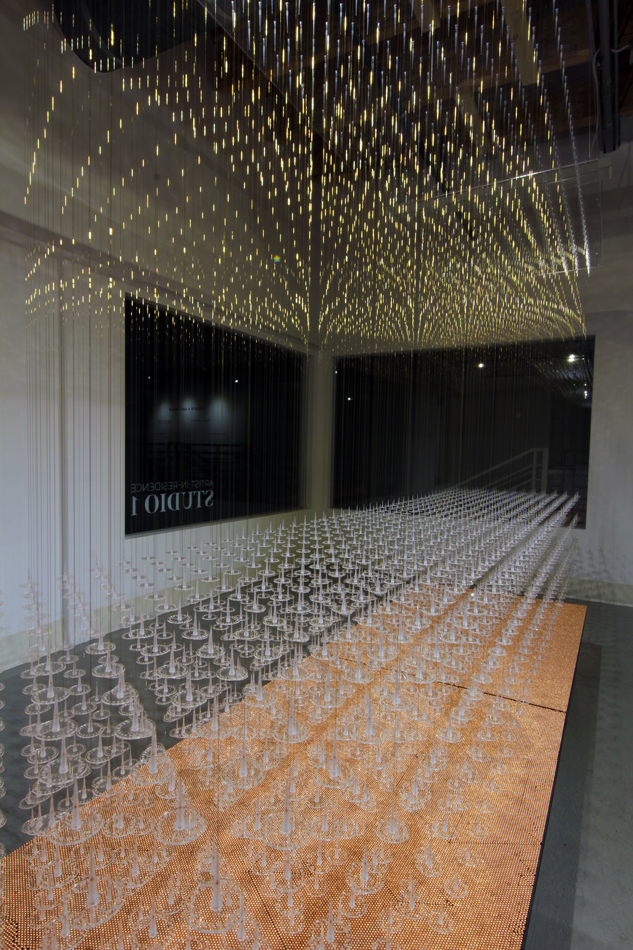

Leitch’s sculptural installations have adorned the halls of every major art institution in the state. Her work was also featured in the 2024 exhibition Materializing Mormonism at the Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum in Arizona. She resurrected an older piece for this exhibition that consists of thousands of “sacrament cups,” vessels used in Mormon religious services to drink water from in homage to the eucharist.

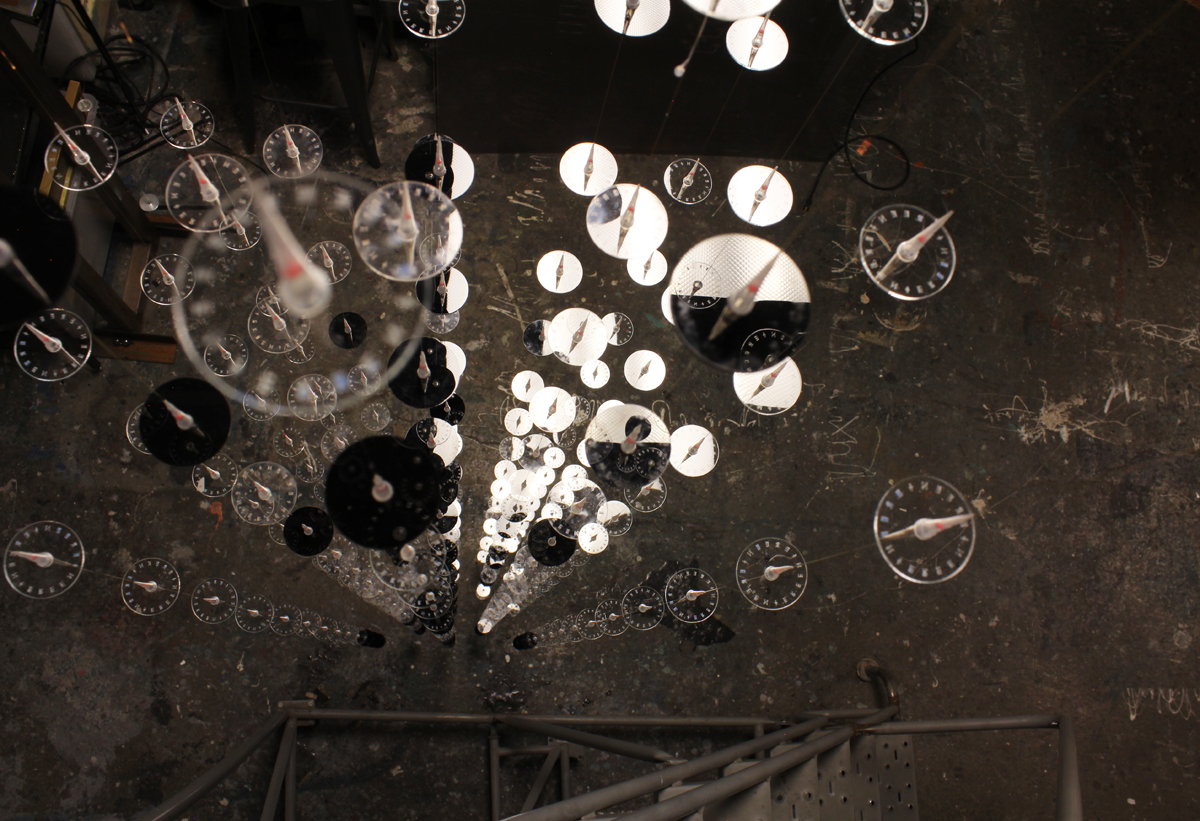

I recently spoke with Leitch at her temporary studio in the University of Utah’s Student Machine Shop in the Department of Engineering. Her latest work—an installation for the Saint George Museum of Art that opens in August—utilizes an isometric grid to spell out words that are faintly detectable throughout the immersive work. Using equipment within the university engineering lab, Leitch harnesses a brass EDM wire for precision cutting distinct words onto small disks on each wire of the installation.

I find constraints really important, but variation becomes nuance and texture.

Her work reflects her fixation on layering and obfuscation, something she links to psychogeography and an obsession with imprinting things on the land. The particular materials she uses are inspired by her upbringing, in particular as the daughter of a medical photographer. “I think my work reflects my obsession with the material culture of the medical field,” she tells me. This inspiration is detectable in the pipe tips (used for medical testing) she uses to bind the material elements together.

She also acknowledges the ways that her work borrows from Mormon visual culture. Leitch takes an anthropological, rather than emotional, approach to this influence. Leitch rejects the seductive trend of translating these influences into heavy-handed satire or biting criticism. Instead, she considers Mormonism a structure to work upon, the visual remnants and ephemera of which are forever imprinted upon her.

“Though I have no religious trauma or doubt about leaving, it still took many years of separation to be re-exposed to the material culture of this ’peculiar’ religion and be inspired to re-appropriate and re-contextualize it in my work.”

While acknowledging the obsessiveness underlying her process, Leitch is careful not to equate precision with perfection. “I find constraints really important, but variation becomes nuance and texture.” So while Leitch exerts ardent control over her creations, she exercises a surprising degree of release regarding how they’re perceived.

She likes covering preexisting images because to her, “nothing is ever empty. Having a blank page is arbitrary. Having a substrate of an image to work upon is key for me.”

Bonnets

A seemingly infinite array of small pearl-tipped corsage pins adorn a bonnet with ribbons dangling symmetrically on each side. Arranged in series, each meticulously crafted bonnet displays a mesmerizing quality that obscures a sinister interior—sharply pointed needles facing inward.

For Angela Ellsworth, the creator of these Seer Bonnets (2008-present), the exhaustive process underlying their creation is a labor of love, an homage to the lives of the individual women they symbolize. This series, and much of her oeuvre, explores the artist’s own familial lineage in relation to the experience of Mormon pioneer women. Ellsworth is a descendant of Lorenzo Snow, who became the fifth president of the LDS Church in 1898.

She recognizes the obsessive inclination underlying her continual attraction to Mormon and familial history as subjects. This fascination is echoed by her exhaustive artistic process.

“One of the first things that comes to mind for me when thinking about obsession is this repetition of walking that is emphasized in Mormon history […] of our pioneer ancestors walking thousands of miles across the plains,” she tells me in a recent video interview. In addition to her sculptural works, one of Ellsworth’s ongoing projects is a multimedia performance art project called The Museum of Walking, inspired by the pioneer lore and musical tradition of Mormon history.

Ellsworth acknowledges that the inspiration behind her work arrived after years of actively avoiding her roots. “As soon as I finished high school, I moved back East and then went to Europe. I ran away from Utah to figure out who I was as a person,” she says.

After living in Europe for six years and returning to graduate school in the United States, Ellsworth realized she had to face her past. Her graduate work inspired her to forge a bridge between her own experience as a queer woman and the lives of the Mormon pioneer women who preceded her.

Indeed, the Seer Bonnets are a fascinating homage to Ellsworth’s ancestry and to any woman whose contributions to a larger movement have been inadequately recognized. In several series of bonnets that represent the individual wives of early Mormon prophets, Ellsworth collaborated with studio assistants tasked with investigating the lives of the women the works honor.

“[The works] are about the juxtaposition of something beautiful and ideal with a notable discomfort,” she tells me. “The contrast between the beautiful and the grotesque is important to me.”

The contrast between the beautiful and the grotesque is important to me.

Such contrasting emotive responses are what make the works compelling and continually relevant. The discovery of sharp needles underneath the scrupulous beadwork of the bonnets suggests something larger about religious propaganda that often relies on a veneer of idealism and the suppression of dissent to foment the faithful.

As gender equality has encountered notable setbacks in recent years, Ellsworth’s series has evolved in an effort to express collective themes of sorrow and outrage. Her newer series of bonnets—including In Arms (2023) and In Memory of our Sisters (Jane) (2023)—symbolize women taking up arms in the fight against injustice.

“As an evolving project, the Seer Bonnets stand in for women and the visibility of women everywhere,” Ellsworth says.

Passports

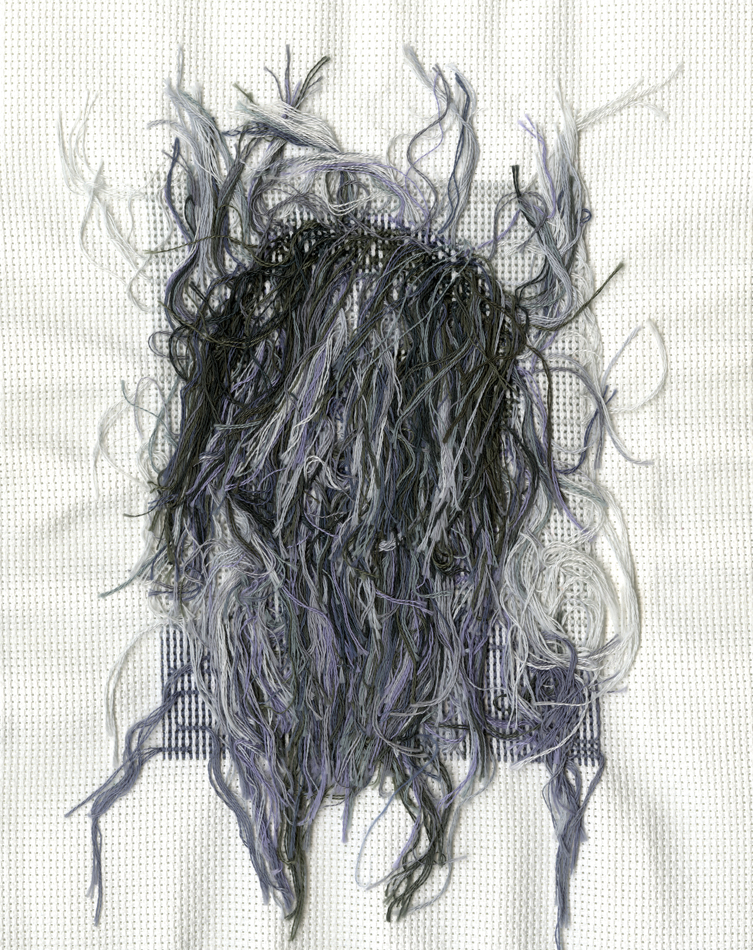

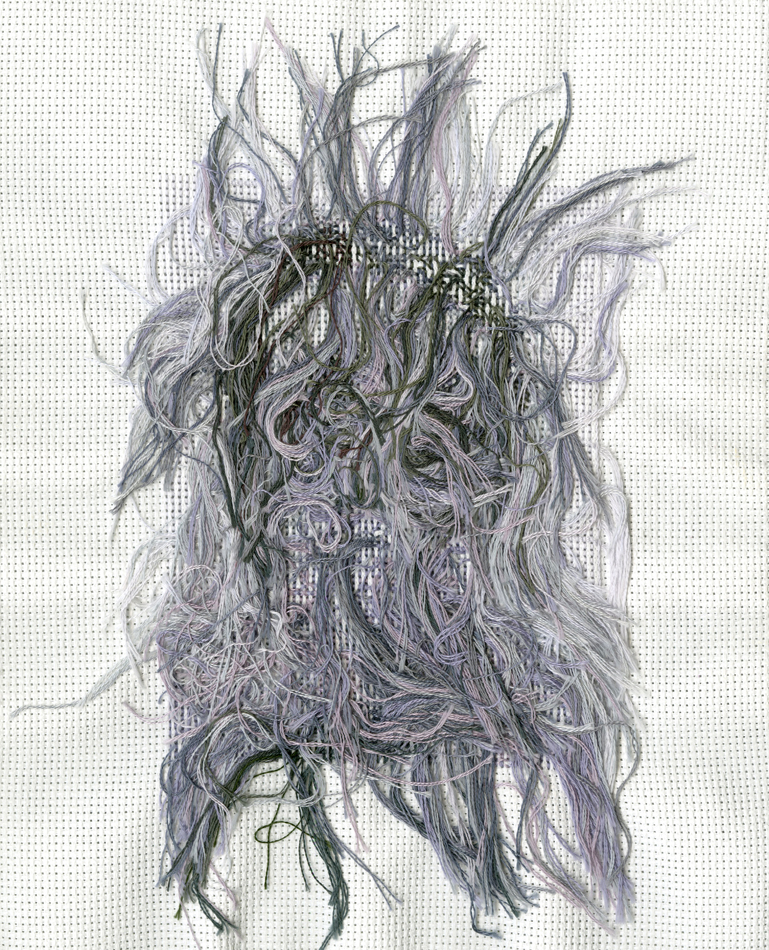

“Normally, the back of a cross-stitch is clean and orderly,” says Nancy Rivera. The multimedia artist is recognized by her formal precision, but an underlying theme in her work is bureaucratic chaos. “I was really intentional about the backs of [these] cross-stitches because their craziness is a metaphor for all of the messiness of the immigration process.”

Rivera’s work, ranging from photographically lush images of arresting floral arrangements to tactile pieces that blur the boundaries between two- and three-dimensional art objects, invite attention on both formal and thematic levels. While much of Rivera’s work evokes a fascination with the material and tactile processes underlying its creation, one series in particular demands viewers to ponder the painstaking nature of its creation.

I was really intentional about the backs of [these] cross-stitches because their craziness is a metaphor for all of the messiness of the immigration process.

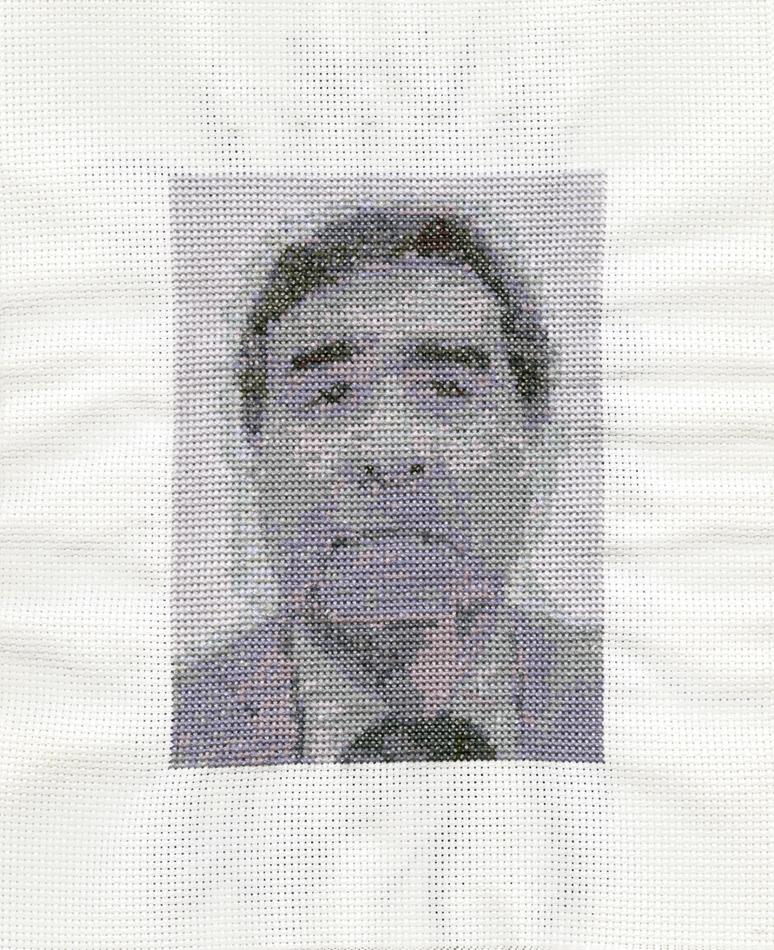

Her Family Portrait (2020) series is a compilation of small embroidered portraits of the artist and her parents at various stages of their immigration journey from Mexican nationals to citizens of the United States.

The works exist in groupings that showcase each individual’s passport photo at a particular moment in time. To commence work on Family Portrait, Rivera crafted digital patterns from the original images of passports, green cards, and naturalization certificates.

Rivera was born and raised, until the age of twelve, in Mexico City. In addition to capturing the multi-year process of the immigration system, Rivera explores the visual tradition of the family album, one particularly lauded within Mormon culture.

“In the American tradition of a family album, they are meant to preserve a family’s history and milestones that show that family’s legacy,” Rivera says. “I thought that by using these images, I was doing the same thing but telling a different story for immigrants that what we have as milestones is the different stages of the immigration process.”

Rivera’s youth was marked by existing in a liminal state—on the periphery of but also within Mormon culture. Although her family converted to the Mormon Church while living in Mexico, moving to Utah as a teenager was naturally a massive cultural shift. It wasn’t until after she completed her graduate degree—and after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen—that she felt emboldened to imbue her life into her work. “Before this time, it felt unsafe to talk about something so consequential that could really change the way people thought of me,” she explains.

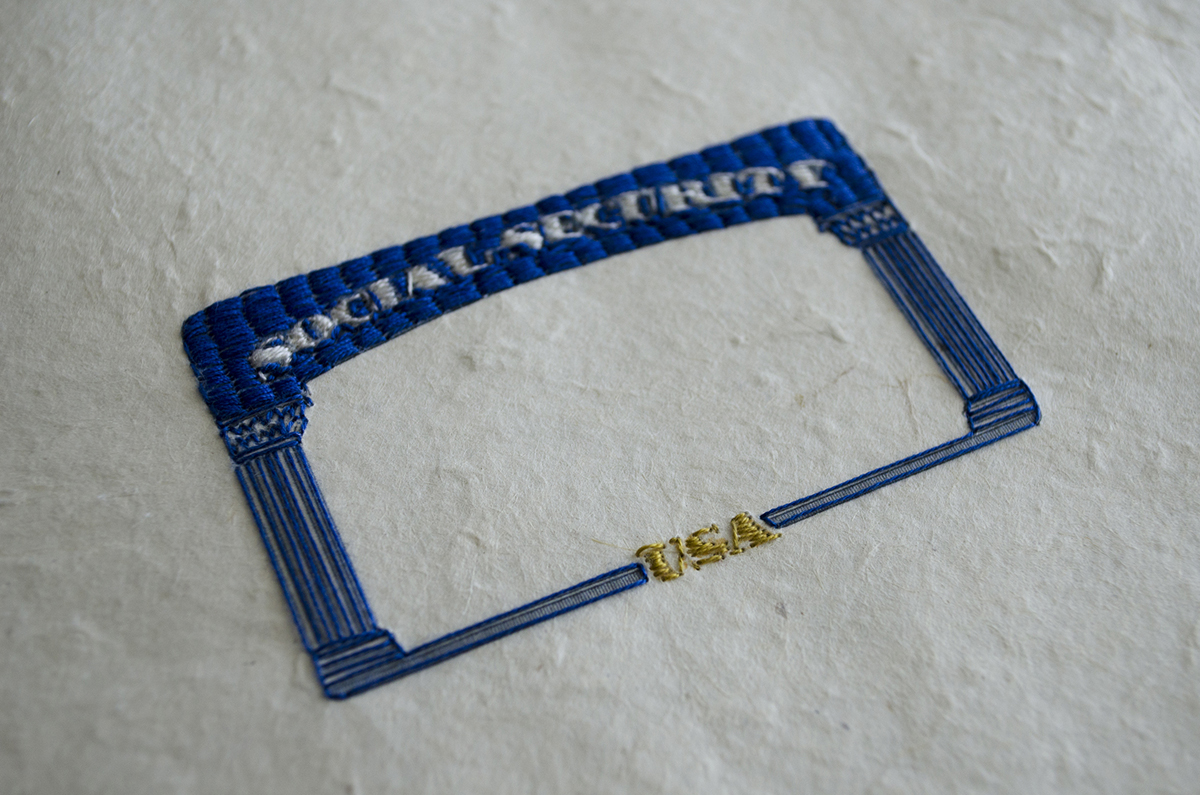

Her work (un)documented (2018) also utilizes embroidery—a medium historically pilloried by the architects of the Western art canon as folk art or “women’s work”—to symbolize her family’s aspirations of citizenship.

The piece is a small embroidered replica of a social security card. Devoid of personally identifiable information, Rivera’s card depicts a pristine white square framed by royal blue columns and white-and-gold text that reads, “Social Security” and “USA.” Stripped of its utility, the framing of this vital document seems kitschy in its ornateness. To create the work, Rivera taught herself to embroider and sought out Nepalese Lokta paper to evoke the scale and tactility of an actual social security card.

The arduousness of Rivera’s artistic quest to replicate the actual document mimics the patience and pain of awaiting the ability to live freely in one’s adopted country.

Repetition Compulsion

Sigmund Freud described a human’s unconscious and insatiable desire to repeat episodes from one’s past as “repetition compulsion.” To him, repetition was an act of gaining mastery over that which torments us, though compulsion may also stem from an urge to repeat the cultural motifs that have limited or defined us.

Obsession is popularly thought of as something the afflicted cannot set aside, either in thought or in practice. For Leitch, Ellsworth, and Rivera, obsession appears as both thematic and material. Each artist, in their own way, uses identity within or outside of a cultural majority as the subject through which a laborious material process takes shape.