Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

April 28 – October 28, 2018

Nearly everyone who walks into the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum has some version of the artist they’re looking for: their Georgia, the one whose paintings they’ve seen so many times in reproduction and an artist whose life’s work has been defined, for better or worse, by flowers and bones. Those earlier Freudian readings stubbornly hang onto their Georgia as does the sense that her work can only be read in one unchanging way.

Yet a handful of institutions are embarking on a new approach: showing O’Keeffe’s work alongside the artistic production of contemporary artists and, in the case of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, alongside contemporary artists of color. The current exhibition at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, The Black Place: Georgia O’Keeffe and Michael Namingha, curated by Carolyn Kastner (now retired), allows two visual languages—O’Keeffe’s and Namingha’s—to mingle. Not only do we get to see Namingha’s digital prints through the prism of O’Keeffe, we get to see O’Keeffe’s vision of what she dubbed the “Black Place” through the prism of Namingha.

With each painting of the Black Place, then, the undulations of the land and curious charcoal and pink coloring transform from places to extremely emotive shapes.

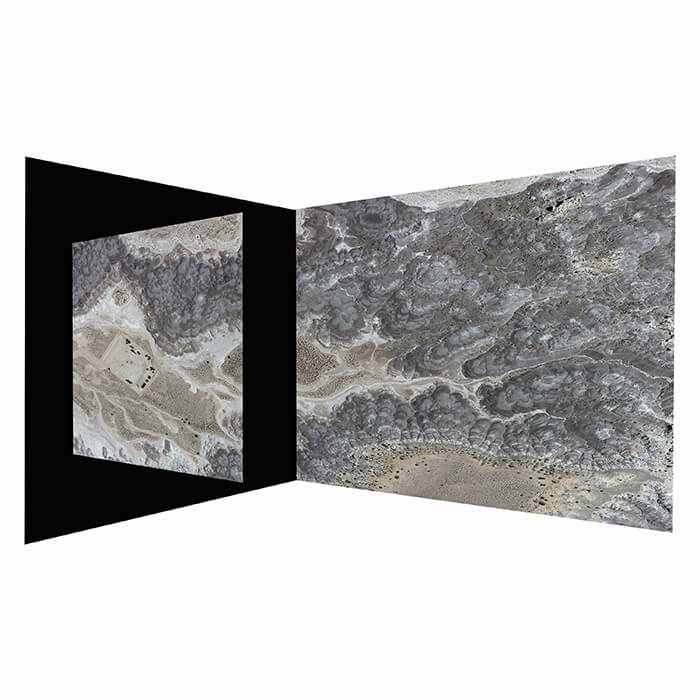

O’Keeffe’s paintings of the Black Place, known officially as Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness, spanned from 1936 to 1949. It was a landscape she visited often and one whose Diné name evokes the petroglyphs of cranes that can be found throughout the area. O’Keeffe’s Black Place paintings aren’t often exhibited together, and, when they are, her obsession with painting a particular site serially becomes obvious. As with other series, including her paintings of the Abiquiu Salita door, her renderings become more abstract over time. With each painting of the Black Place, then, the undulations of the land and curious charcoal and pink coloring transform from places to extremely emotive shapes. With the most recent fracking boom, the hills O’Keeffe once depicted as solitary and untouched are far from either. Even in her time they weren’t. Still, for me, these are some of the most compelling paintings of the artist’s career, in their richness of grays and the somberness they convey.

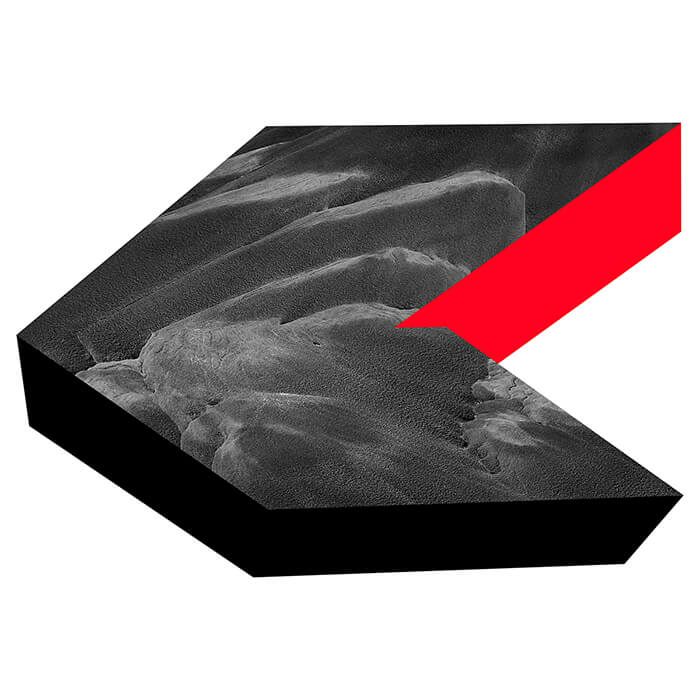

Nearly eighty years after O’Keeffe made her treks to the Navajo Nation with her companion Maria Chabot, Namingha visited the badlands with a drone in hand, capturing a much more expansive, yet still abstract, perspective of the landscape. Namingha’s digital prints mounted on plexiglass, a technique which gives the surface a sense of translucency, are similar to O’Keeffe’s paintings in their unwavering commitment to representing the landscape. And like O’Keeffe’s paintings, his mostly-aerial views are familiar as topography, even as they defamiliarize how viewers usually approach landscape as a genre. Namingha’s mode of cropping his oversaturated black-and-white landscapes into angular forms further displaces the landscapes from their origins. Yet in one, simply titled Black Place, we can see a fracking extraction platform, an almost imperceptible blip in the artwork, and a relatively new and toxic addition to the landscape. And with jutting bodies of color—acid yellow, crimson, black, and hot pink cutting into the gray slopes, the prints impart the feeling that the landscapes at hand are increasingly man-altered.

Rather, what Namingha shows is the extent to which landscapes are intervened upon even in their solitude, a sentiment O’Keeffe once made her signature.

It’s clear that both artists achieve abstraction through realism. Because of this shared gesture, the exhibition doesn’t necessarily lend itself to a place-based vision of the Bisti Wilderness. Rather, what Namingha shows is the extent to which landscapes are intervened upon even in their solitude, a sentiment O’Keeffe once made her signature. This is not an environmentalist take by any means, but both Namingha and O’Keeffe—installed across from one another as if in dialogue—not only disarrange space but also our perceptions of it.