Denver artist Suchitra Mattai challenges Western traditions of painting through her use of culturally specific materials that are informed by the South Asian diaspora.

Sitting in her Denver studio, multi-disciplinary artist Suchitra Mattai—represented locally by K Contemporary—notes that her “work speaks to the global, so I want it to have a global presence.” Indeed, her work does occupy a global footprint, having shown at the Sharjah Biennial 14, Unit London, and Hollis Taggart in New York City. This expansive vision extends not only to where she exhibits, but to her sense of self and artwork.

“I believe that we all are global citizens,” Mattai says. “And as a global citizen, it’s important to be aware of what’s happening outside of our comfort zones and communities. The more informed I am politically and socially, the more complex and rich my own practice can be.”

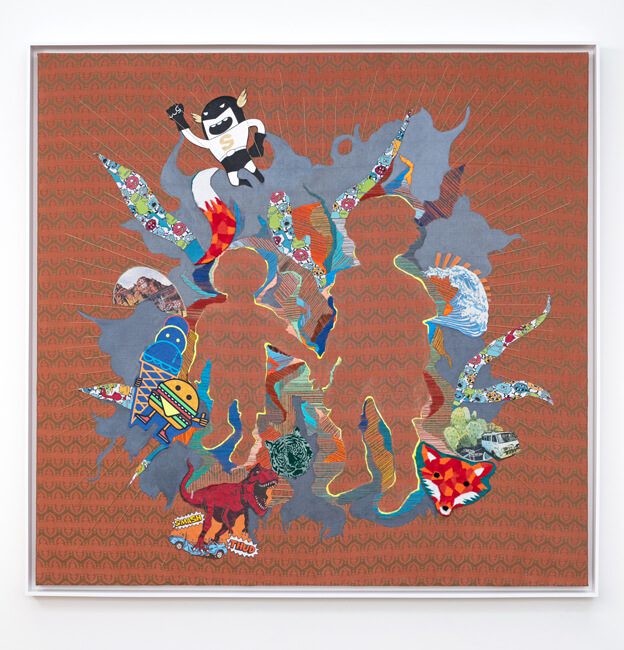

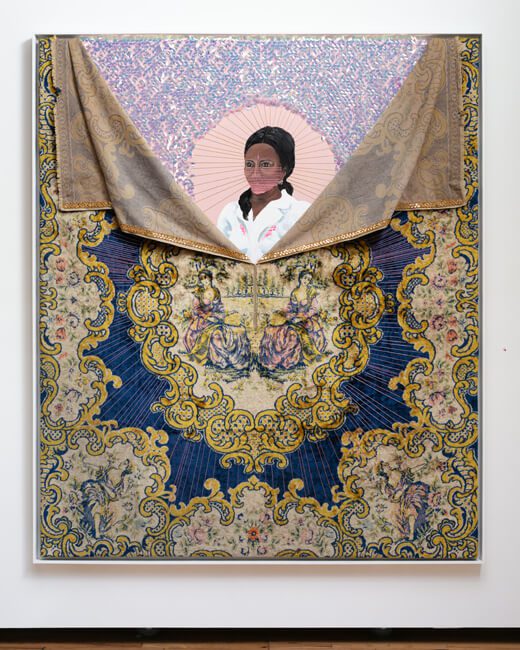

The complexity and richness of her artworks are certainly evident within her workspace. Ornate, multi-colored patterns of vintage saris woven into tapestries drape from the fifteen-foot ceiling. Mixed-media paintings bedecked with fiber, beads, and found objects hang upon the walls. Sculptural assemblages rest upon tables and the floor.

The fact that Mattai’s conceptual, aesthetic, and material interests attend to cultural and political issues at the global level does not mean she discounts the local. “Being outside of one of the major cities of artist production allows for a certain freedom that larger cities don’t,” says Mattai, who appreciates Denver’s “thriving artistic community… I experienced my artistic renaissance here. It wouldn’t have happened elsewhere. The support that I’ve had from the people here has given me life.”

Embracing the productive tension between global and local comes as no surprise, given her history. Of Indian descent, Mattai’s family traveled as indentured laborers to Guyana, working on sugar plantations under British colonial rule. During the 1970s, the family immigrated to North America, where the artist was reared in New Jersey and Canada.

As the child of immigrants, Mattai lived within a liminal space that would directly affect her future art practice. “There was always this dual life, and this is the case for many immigrants,” she explains. “There’s the cultural home life, and there’s this other life you have to experience [outside the household]. This dual identity has always been something I’ve wanted to communicate to others.”

Searching for the best way to express her complex identity and concepts of home, Mattai enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia where she earned an MFA in painting and drawing and an MA in South Asian art. While UPenn is undoubtedly a prestigious institution, Mattai says that her program relied on thinking and making “through a Western framework and history of painting,” which made it challenging to explore the issues concerning her.

Although she incorporated alternative and non-painterly materials into her work during graduate school, it wasn’t until she moved to Denver in 2007 and subsequently became a Redline resident that she veered from Western traditions in earnest.

“I can’t tell a different narrative in a medium that doesn’t belong to me. Obviously, it belongs to me in some ways. I went to school in the West, but there are materials, an intuitive reconciling of disparate parts, and do-it-yourself [sensibilities] in the Caribbean,” says Mattai. (“Guyana is geographically in South America,” Mattai notes, “but culturally it is part of the Caribbean. So it’s this very liminal space.”) Mattai recalls this period of her career as “an awakening in how to express my culture: finding, exploring, and uncovering this past, experimenting with materials in a joyous way.”

Mattai intentionally works through several modes of production and a variety of materials, such as painting, fiber/textiles, video, and installation. Two of her more distinctive practices, though, are her sari tapestries and furniture-based installations.

“For the Sharjah Biennial,” she remembers, “I knew that I wanted to create monumental tapestries, which I thought of as collages. I wanted to use material that was very much of South Asia.” She decided upon saris, valuing their vintage quality.

Moreover, they were worn and “of the body, honoring women of the South Asian diaspora,” she says. “I wanted to weave, as part of my narrative, this idea of connections over topography and time between people from a particular place.” To this extent, Mattai employed a traditionally domestic practice as a strategy for exploring post-colonialism, displacement, and immigration.

With her furniture assemblages, the artist is “trying to tell stories through materiality—trying to uncover and share these experiences in a way only installation can do.” These artworks convey an idea of “what it is to create a new home or a mythic past” by engaging concepts of “migration and how memory shapes our attitudes and feelings toward the past. And how mythic it can be. An idealized version of the past.”

“Having lived in all these different places, I am a nomad. I don’t see myself connected to only one space or one community,” says Mattai, who adds that she wants “to find a way to tell multiple perspectives of a story in each one of my works.” In doing so, she reconciles competing tensions into a productive, creative, and aesthetically compelling manner.