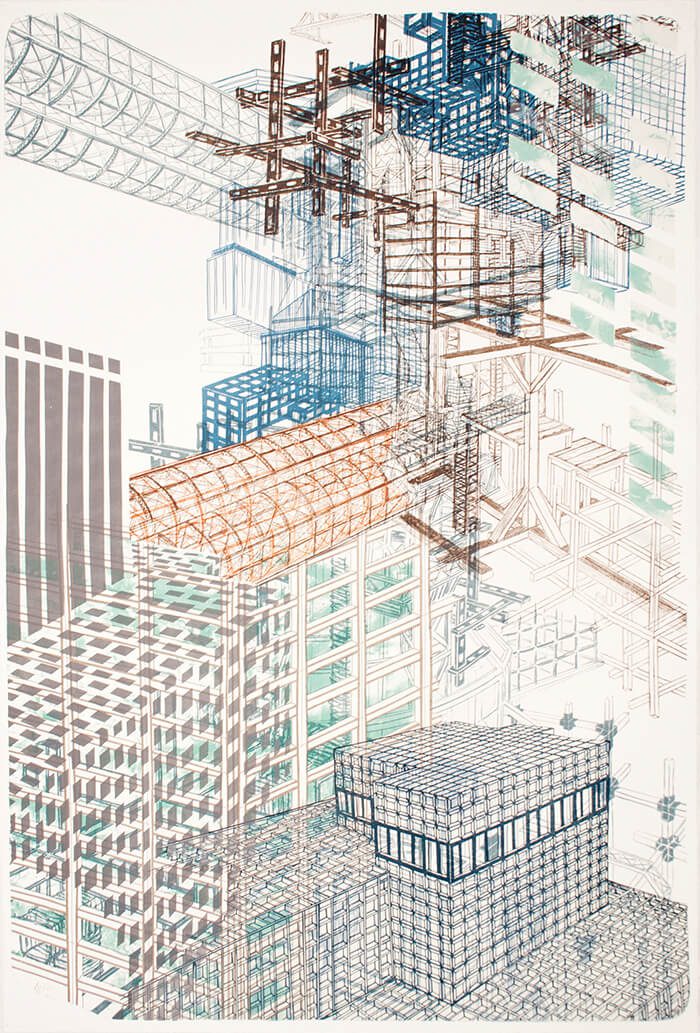

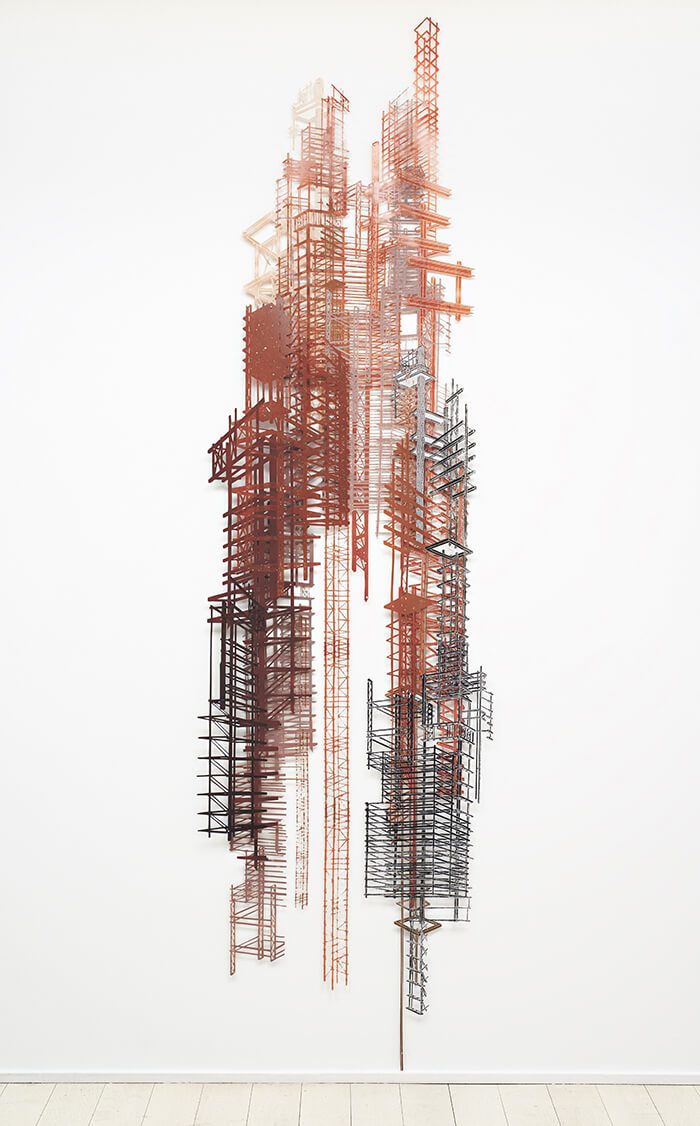

Nicola López uses printmaking, drawing, collage, and large-scale installation to create work that explores the physical and psychological experience of the contemporary city. Born and raised in Santa Fe, López lives and works in Brooklyn, New York, and teaches at Columbia University. She was recently artist in residence at Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, where she was tackling some new themes in her work, including a resurgent interest in organic forms as they find corollaries to the ever-accelerating growth of the urban landscape.

Clayton Porter: Did you move from Santa Fe to New York? Was that jarring, moving from a horizontal to a vertical perspective?

Nicola López: I didn’t think that it was going to be jarring. But it really was. It’s not just the city environment. It’s a transformative experience to leave your home, and to leave your family, and to leave the land that you’re from. I think that that sunk in over time. One of the questions that I get a lot is what the relationship is between the urban landscape and the non-urban landscape, because my work deals with that directly in a lot of ways. I don’t draw or include images of the New Mexican landscape, but it’s always the foil that I’m working against, because it’s what’s deep down in there, in terms of my non-urban reality.

These structures, the sense of architecture and construction that you’re working with now, did that happen right away? At what point did you find that voice?

I made a lot of art growing up. But I didn’t see myself as an artist, first and foremost, until maybe starting during college. And it really sank in afterwards. Even my sense of self as an artist—as having an artistic voice—didn’t happen until a little bit later. I think back to the work that I was making in undergrad, and the imagery was a lot more organic, it was not about architecture at all. And, of course, now I’m looking back, going, “huh.” There were some ideas there that I find myself repeating or getting back into, which is always interesting. As an artist, you’ve got a good visible track record, so it’s easy to see what kinds of things pop up again and again.

I think that the actual imagery that is more recognizable and present in my work now, as far as architectural urban layout, came about close to the time between undergraduate and grad school.

As an undergraduate, I majored in anthropology and had a concentration in visual arts. I had no intention to become an anthropologist, but that has definitely framed my perspective—and continues to frame the way that I think about not just my work but about the landscape, about the city, and about the structures as reflections of human culture. That you’re not just a product of this, but it’s also this thing that you can observe and extrapolate from.

I was doing a lot of woodcuts and printing them out by hand. I had all these blank studio walls, you know, and started putting the prints up, making this collage—using the page as the context, then using the floor as the context.

When you’re a printmaker, or a photographer, a lot of times work goes straight to the frame. It doesn’t jump off and do other things. When did you start working in these sculptural installations? Was it a “Eureka!” moment?

I think it actually started happening in undergrad. A little bit, just using prints, cutting them up, putting them on different surfaces. Although, it’s kind of funny: I’d kind of forgotten about that. For a long time, I kept pointing to this one project that was really important for me: I did a residency, a summer residency program called Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and I was doing a lot of woodcuts and printing them out by hand. I had all these blank studio walls, you know, and started putting the prints up, making this collage—using the page as the context, then using the floor as the context. It got this dimensional thing going on that felt so new and so different, and that felt like a huge “Eureka!” moment. Years later, I ended up going through all these slides and old photos of undergrad, and I went, “Wait a minute!” So there were tendrils of that happening maybe as early as undergrad, but I don’t think that I was able to really articulate it in a way that could be continuous and grow in a studio practice. Grad school helped me to realize that and push it and challenge it. I had a lot of voices that asked key questions at key times. It facilitated production in ways that I could make those leaps.

When did printmaking come into your toolbox?

I went to Santa Fe Prep, and they have a really great arts program, but they didn’t have a print shop. The artist Zara Kriegstein came in and did a little workshop. I just thought that it was so cool; it really grabbed me. At this point I’ve realized that there’s a part of me that really loves the thinking and invention of creating imagery. But it’s the problem-solving that’s inherent in printmaking, and there’s this heavy kind of process (which would drive me crazy if I had to do it all the time), but as an element of what I do in my studio, I find it really rewarding. It is one of the real foundations of a lot of my work. I also do a lot of drawing that doesn’t interface with printmaking. But print has become a way of making much larger work—it’s a way of generating material and working with variations, and I think that it also resonates thematically with the work and with the environment that I’m talking about: this mass-produced, mechanized, technology-based, built landscape. There’s a nice parallel with the process of printmaking in its capacity as a means of reproducing imagery.

It looks like you have some reference material from all over, so you brought that with you, you had an idea. What did you have to prepare in coming to Tamarind for this two-week residency?

There is a photo up there of a tree that has these wooden struts kind of supporting it, and that was a site-specific outdoor sculptural installation. This tree was actually cut down and being transported. So it was in pieces, and I reconstructed it and added scaffolding. This was something really new, and I’ve wanted to get back into that idea, and work with it a bit more. I thought that this was the perfect place to do that—in a different way, with different materials.

The idea of the relationship between nature and the human-constructed landscape/technology/architecture has always been really present [in my work]. Not in a visible way, but in this life-cycle of cities that grow and decay, that take on these organic attributes of tangling wires and buildings that are growing and out of control. All the language is still about this natural process, and this is just making it a little more literal. What I’m doing here is using those different ingredients of imagery but making prints and putting them back together. I don’t know how it’s going to happen, still. I know the general realm, and all these photos are different references, bits of that conversation.

I don’t know if it’s rare to see an artist using photographs on the wall, because devices are so prevalent. You feel that they immerse you in what you need to do? As opposed to just flipping through a screen?

Totally. Yeah, when you flip through it on your screen, you only get one at a time, and you have to hunt and peck for it at the moment that you want it. For me, I’ll have an image around in the studio; it’s not pointing at anything in particular—but I really love that image, I don’t know why. It’s like a reminder, and there’s something about having these notes and reminders that are coming in, not when I’m looking for the device, but when I’m kind of spacing out, and all of a sudden it’s like, “Remember me? I’m this little idea. Don’t forget about me. This is important, or this is interesting. You don’t really understand me, but here I am.”

Your studio in Brooklyn—is it the same there, you have images everywhere?

It comes and goes, and sometimes things build up and there will be a lot of images around, then I’ll clean stuff out. But there’s something about having the physical thing, and that is a part of what I do: I make physical things. It’s not just images.

There’s always a desire to figure things out and feel stable. But then you want to shake it up a bit—and life comes in and shakes it up for you. I don’t feel like I’ve arrived at my final destination. I hope I haven’t.

I think about it a lot as a teacher, and the students that I work with, there’s a kind of intelligence that art making can encourage that is in addition to verbal articulation and in addition to visual image creation that is about making a thing. It’s the interaction of the physical intelligence—and the embodied intelligence, and the experience of interacting with materials—and the verbal articulation and the visual kind of creation that is really powerful. I think we’re so capable. We’re made to interact with the world physically. That’s how I like to make work. Even if it ends up on somebody’s wall in a frame, I think that people react to things viscerally, even on unconscious levels.

You’ve had a lot of success, in terms of your career. Do you feel like you’ve “made it,” or are you still “making it”? What’s your perspective on the future?

I can’t imagine feeling like life is this static thing that has been figured out definitively. In my experience, that’s not how life works, and I don’t think that I would feel so happy, if that’s what I felt. There’s always a desire to figure things out and feel stable. But then you want to shake it up a bit—and life comes in and shakes it up for you. I don’t feel like I’ve arrived at my final destination. I hope I haven’t.

There’s always something to aim for and try to do next. There’s always something that I want to make next or another opportunity that I would love to try to figure out how to connect with.

Do you think your work is going to get bigger? That it might be something even grander in scale?

I think that the words are. . . slippery. This is maybe a parallel to human cultural life in general, to talk about things in terms of progress. It’s tempting to look at history as a progression toward a destination. And I’m not sure that things are progressing, in terms of a positive/negative scale. On a personal level, I don’t know if it’s about getting grander or bigger. Better? Yeah, I hope it’s going to get better. Different, new, deeper, challenging. Yeah, I definitely want that for myself. That’s an amazing thing about being an artist, there is not a mapped out destination like, “Okay, you’ve gotten your highest rank. You’re there.”

Again, I think of working with students, because I have students all the time who are like, “How do I ‘make it?'” or “What’s the formula? Give me a roadmap here.” It’s really difficult to be in a profession or life-path where there is no roadmap. Yeah, it’s nice to have work collected by the Met or MoMA. You get these nice little stamps that maybe people agree on as milestones. But you don’t have to do that in order to have wild success on some level. You don’t have to be internationally recognized, I think, to be wildly successful. You define your own levels of success, and that is a really powerful thing. It’s not an easy thing to do, in life, for many of us in general. But as an artist, there’s nothing less successful about an artist who has a really vibrant practice and life within a community that might be small, in terms of numbers or geography—or even has a really rich relationship with their own studio work, period—and doesn’t leave, or doesn’t leave very often. I don’t think that’s inherently less successful than somebody who’s shown here and there, travels, and gets invited to things and paid for things.

There have been times that I have felt more of an urgency, like there’s something that I need to do in order to make it, somehow. This nebulous idea of “making it.” Maybe it’s because I’m worrying about enough other things—I have a young child, and I have a more stable situation with teaching at a great place and knowing that I can make my work and continue to make it—that I’m not worrying about those basic things. I feel like I’ve made it on the days when I don’t feel angsty about “making it.” [Laughs.]

You obviously love teaching; you love the place you’re at. But if you could be in the studio full time, would you?

I think if I made the choice, the commitment to try to be in the studio full time and have that be my only source of income, there would be other levels of stress to the relationship to my studio that I just don’t want right now. Would it be possible? Maybe. Has it been possible in past years? Maybe sometimes. Not with the level of consistency that I would be willing to go into it right now, especially with a young child. I think it’s different when you have that. I don’t want art to feel like a constant hustle, and I think that, where the money is involved, sometimes it can feel like that.

There are so many different ways to be an artist, but if you do want to live off of the artwork, there is the business of the studio, the public interaction part of it, the archiving, administrative part, and that can be overwhelming. It’s tough making it the only source of income, because those things become total necessities.

That’s one side of it, and then the other side of it is that I actually really do like teaching, and it is partly about having different interactions around art. My whole professional life is still focused on art and art making and conversations that I want to have, as opposed to having another job. Speaking with students about their practice, thinking about growing as an artist, having those conversations, just being in a place where there are new ideas happening, where people are trying things and talking about it—I like talking about art. I have amazing colleagues who are doing such exciting things. There’s just so much in that larger environment. It nurtures me as a person and as an artist. It’s like exercising all these different muscles, and in the studio I exercise only some of them. It’s nice to have a place that pushes me in those other directions as well.